Growth and Upheaval in the Network Media Economy in Canada, 1984-2020

Recommended citation: Winseck, Dwayne, 2021, “Growth and Upheaval in the Network Media Economy, 1984-2020”, https://doi.org/10.22215/gmicp/2021.1. Global Media and Internet Concentration Project, Carleton University.

Contents

Summary of key findings and insights

The Network Media Economy in Canada: Contemporary Trends and Ongoing Policy Debates

The Telecoms and Internet Infrastructure Sectors: Bandwidth is King, Not Content

From Plain Old Telephone Service to Broadband Internet Access and Internet Protocol TV

Broadband Policy, Politics and Public Interests: One Step Forward, Two Steps Back?

As Internet Advertising Soars, Total Advertising Spending Slumps

The Rumoured Death of Television is Much Exaggerated

Pay and Specialty (Subscription) TV

Online Subscription and Download Audiovisual Media Services (AVMS)

The Total Television Landscape in Perspective

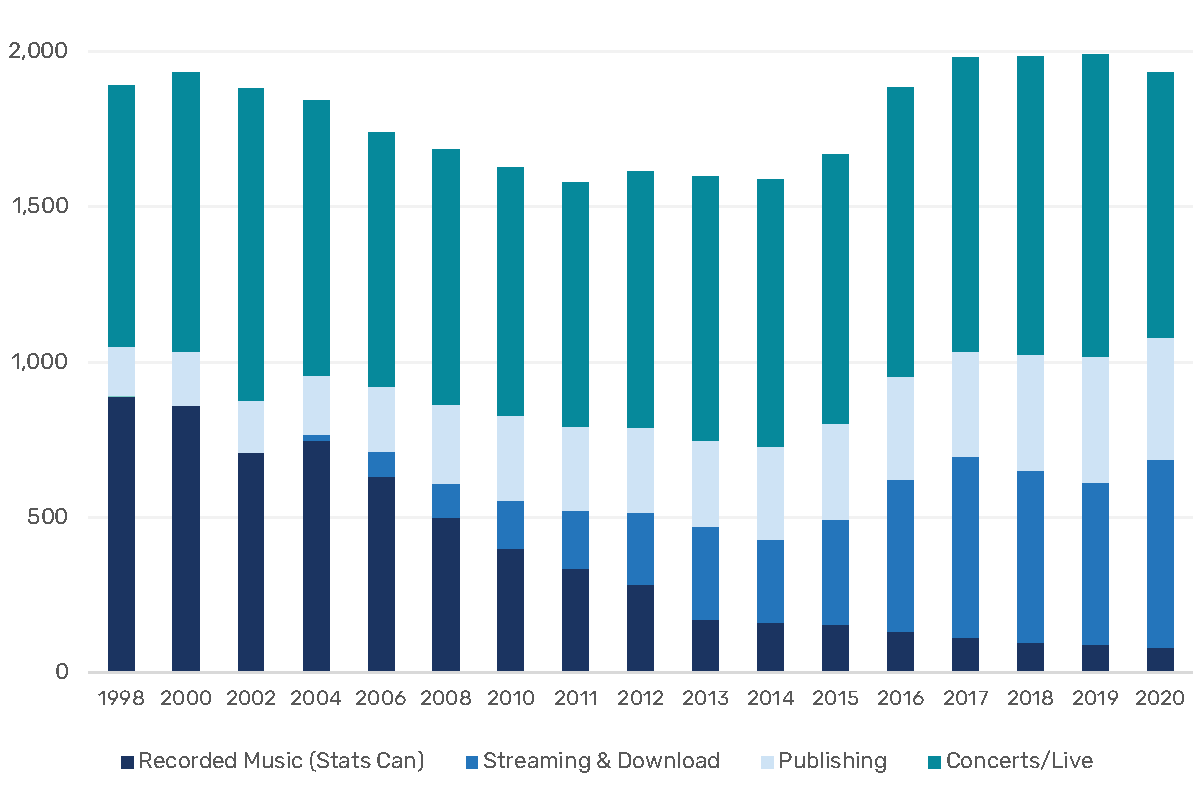

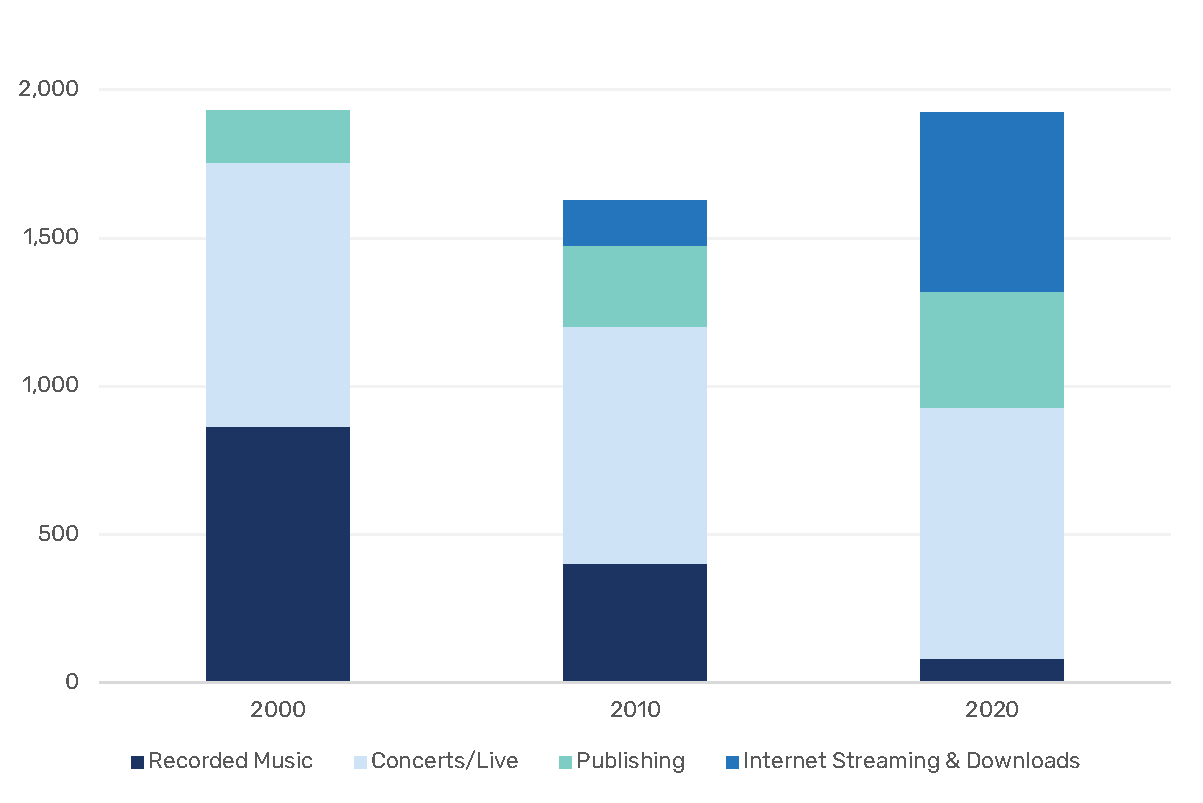

Remaking the Music Industry: From Ruin to Recovery

Newspapers and Magazine Publishers in Peril

ANALYSIS – Some Reflections on Journalism, Public Subsidies and Public Goods

Some Concluding Observations on the Political Economy and Power of Communication and Culture Policy

This is the tenth edition of Canadian Media Concentration Research Project’s first report in our annual two-part series on the state of the telecoms, Internet, and media industries in Canada (previous versions can be found here). It examines the development of the media economy in Canada over the past thirty-six years.

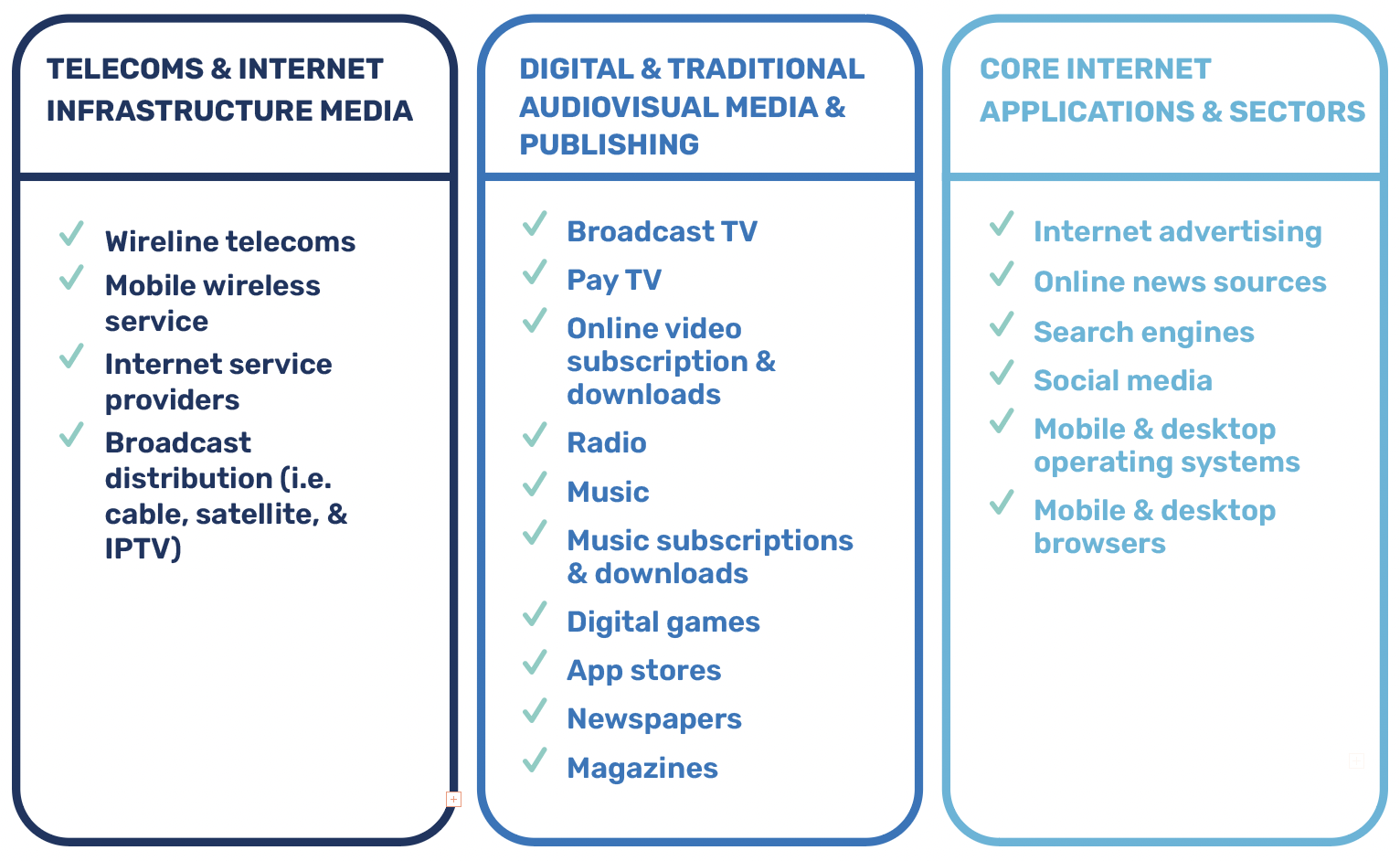

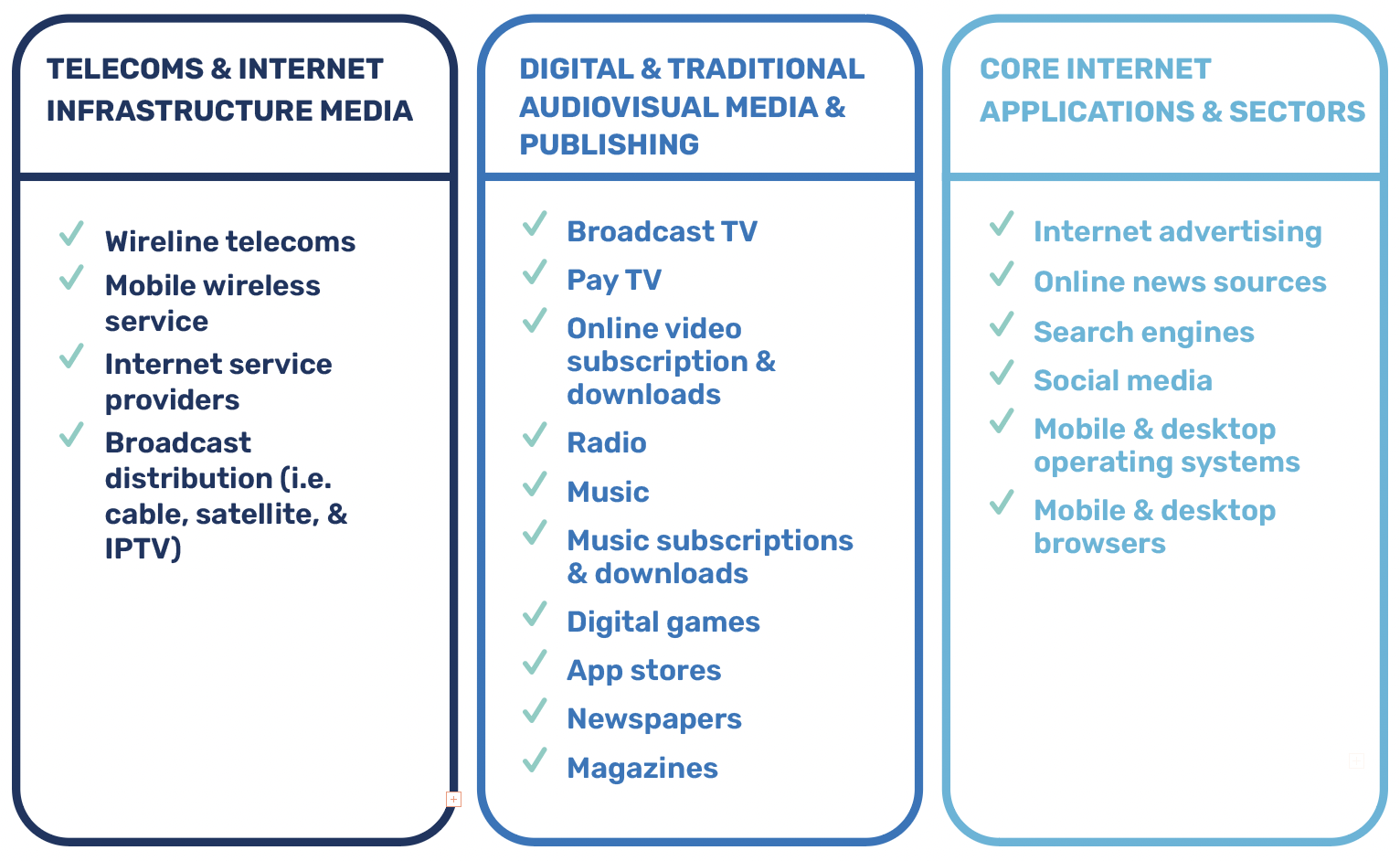

Since beginning this project a decade ago, we have focused on analyzing a comprehensive as possible selection of the biggest telecoms, Internet and media industries (based on revenue) in Canada, including: mobile wireless and wireline telecoms; Internet access; cable, satellite & IPTV; broadcast television, specialty and pay television services as well as Internet-based video subscription and download services; radio; newspapers; magazines; music; Internet advertising; social media; operating systems; browsers, etc.

In recent years, we have made some fairly dramatic changes in order to capture a broader range of audiovisual media services that are delivered over the Internet beyond online video subscription and download services and Internet advertising. The new sectors brought into our analysis since then include:

- Online gaming, gaming applications, game downloads or in-game purchases (Digital Games);

- App stores, in particular Google Play and Apple Appstore;

- Music downloads and streaming music subscriptions.

We classify these sectors as the digital audiovisual media services, or digital AVM services for short, a category that includes online video subscription and download services such as Netflix, Crave, Amazon Prime Video, Disney+, Club illico, CBC Gem, Apple iTunes and Google Youtube Premium and Youtube TV. We also distinguish these online video services from their legacy counterparts (e.g. broadcast TV, specialty and pay TV, radio, music, newspapers, and magazines) that do not rely on Internet aggregation and distribution as a core part of their business models.

Figure 1 below depicts the segments of the digital and traditional media industries that collectively comprise what we call the network media economy.

Figure I: The Network Media Economy in Canada—What the CMCR Project Covers

The research method that we use is simple: we begin by examining the individual components of the network media economy (i.e. the sectors indicated in Figure 1 above). This involves collecting, organizing, and publishing stand-alone data for each media industry individually. We then group related, comparable industry sectors into three more general categories: the “telecoms and Internet infrastructure media”, the “digital and traditional AVMS” and finally, “core Internet applications and sectors”. Ultimately, we combine them all together to get a bird’s-eye view of the network media economy, taking care to explain how the sectors interact with one another and fit together to form the network media economy as a whole. We call this the scaffolding approach.

Following this approach ensures that we start with a clear, precise definition of “the media” so that readers know what is included in our analysis and what is not. It also helps to ensure that apples-to-apples comparisons are being made with other studies and research reports, both within Canada and internationally. Too often, debates in this area proceed without such an explicit definition. Consequently, some researchers cast a conceptual net so wide that the defining details of specific media are difficult to discern in their analysis, while others cherry pick sections of the media that support whatever story they want to tell. The problems that this raises for public discussion and public policy formation with respect to the communications, Internet and media are enormous, especially now when these debates are on a high boil, in Canada and around the world. We will discuss the nature of those problems at length in this and the next report.

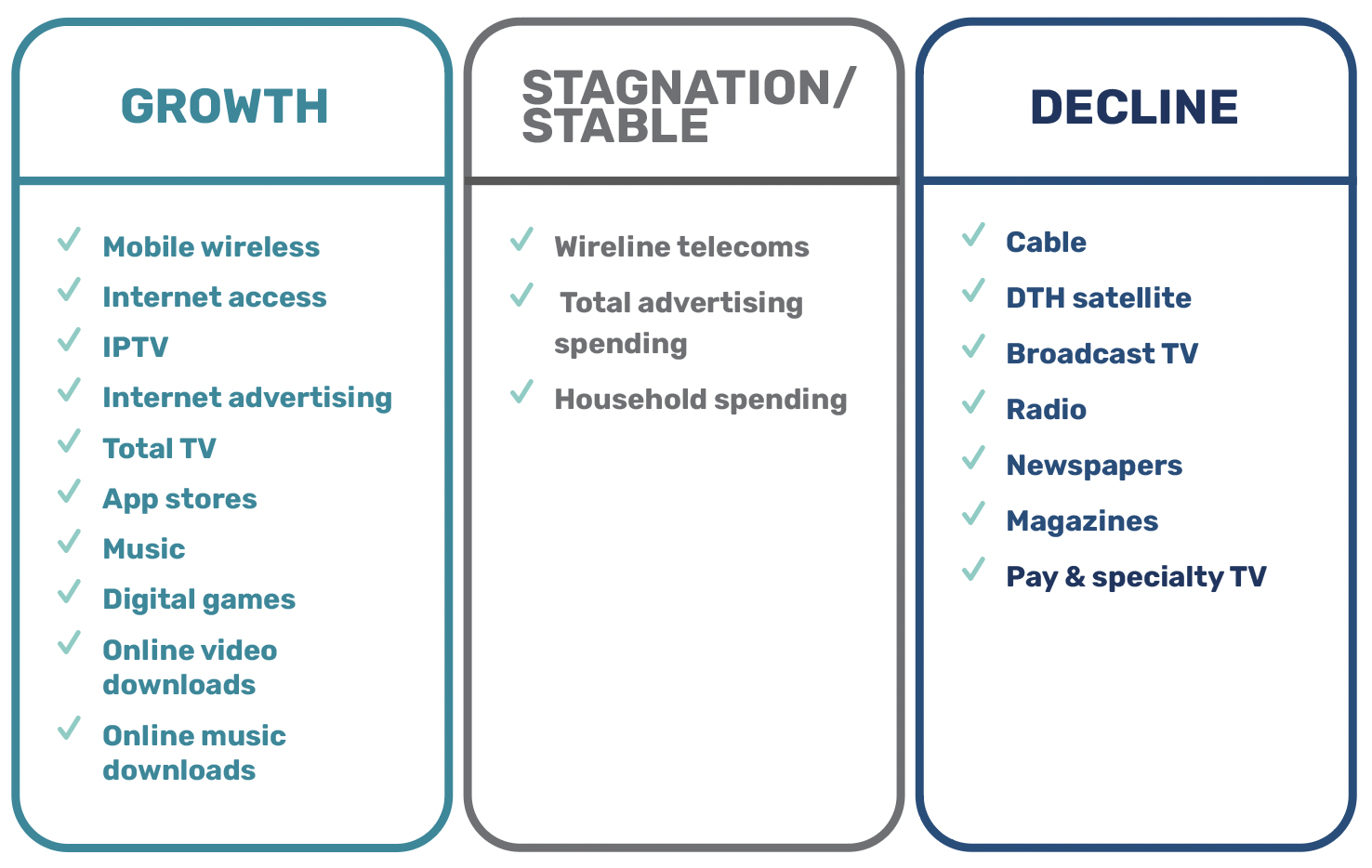

The scaffolding approach not only allows us to focus on the details and relative scale of the various individual segments of the network media economy, but it helps to see how they all fit together. In concrete terms, this allows us to see how major domestic actors stack up when measured against the activities of global players within the Canadian context. Lastly, this approach reveals which of these industries are growing, which are stagnating, which are in decline, and which appear to be recovering after years of misery. Table 1, below, offers a high-level snapshot of where things stood at the end of 2020.

Table I: The Growth, Stagnation and Decline of Media within the Network Media Economy, 2020

Beyond the overall direction of developments within specific sectors over the past year, the report identifies several major ongoing developments in Canada’s network media economy:

- Last year, the growth of the network media economy stalled in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic, with overall revenue slipping as a result. The longer run story, however, is one of growth, upheaval and increased complexity. While several sectors of the media that have historically relied predominantly on advertising funding as a core part of their business appear to be in terminal decline—i.e. broadcast television and radio, newspapers and magazines—there is no general crisis of the media in Canada.

- Despite a continued focus on advertising revenue in much communication and media scholarship, public debates and policy circles, the fact of the matter is that revenue from subscriber fees and direct purchases are at the centre of the media economy. Indeed, revenue from subscriber fees and direct purchases outstrip advertising revenue by a nearly 5 to 1 ratio. It is also critically important to note that the total scope of advertising spend for all media has been relatively fixed over time, and actually fell or stagnated for much of the last decade in inflation adjusted terms, on a per capita basis and relative to the size of the overall economy. At the same time, advertising revenue continues to shift to Internet behemoths such as Google and Facebook. Consequently, there are four sectors of the media dependent on advertising—and the firms that operate in these sectors—are battling the world’s largest Internet companies to retain a share of the relatively stagnant pool of advertising dollars.

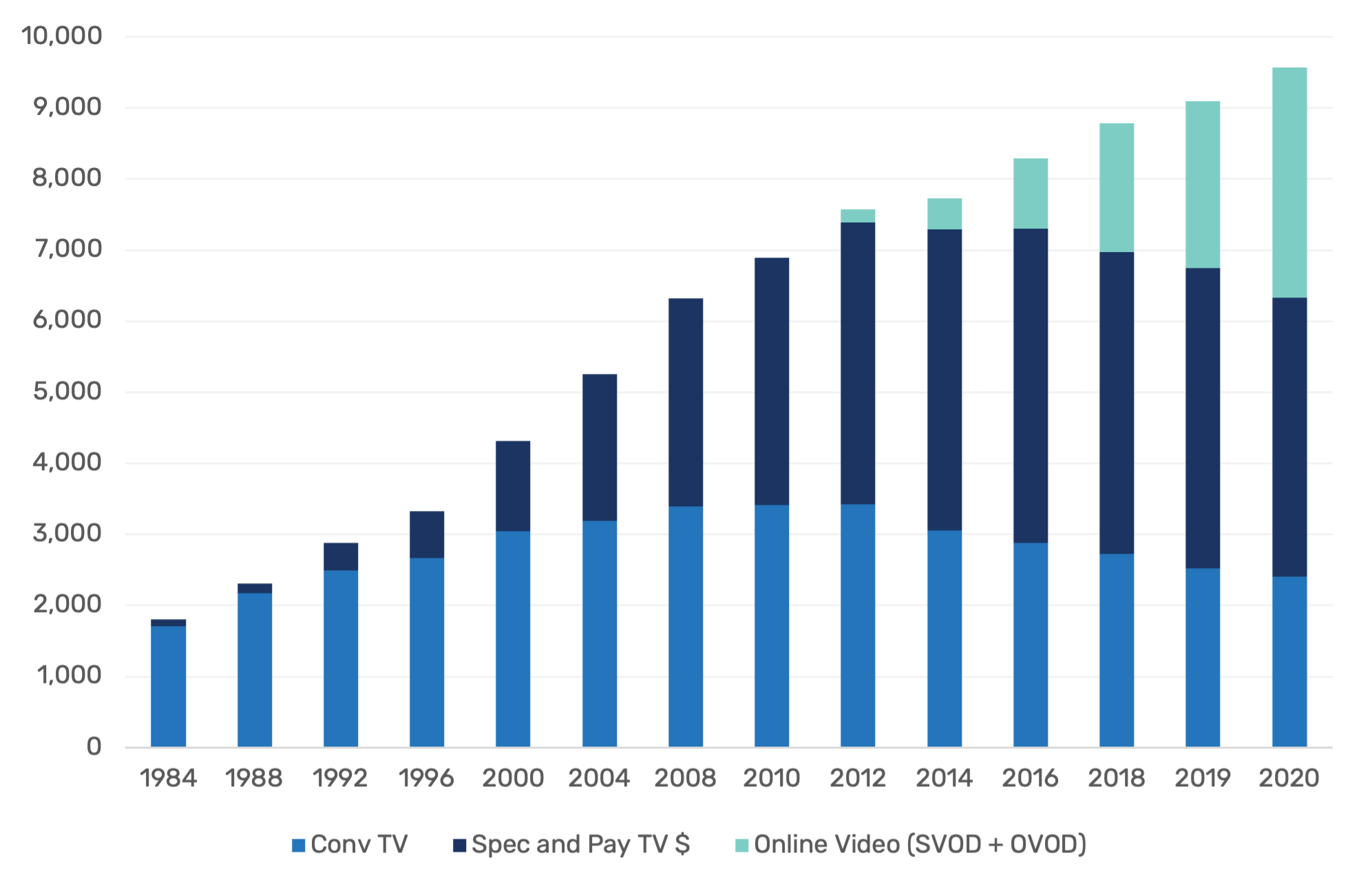

- Contrary to narratives overly focused on broadcast television, Canada’s audiovisual media services market has continued to grow swiftly over the years, and the pandemic gave this an added boost as services like Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, Crave, Disney+ and Rogers SN Now grew even faster than they had been. This offset flagging fortunes in other segments of the TV landscape.

- The story is even stronger for investment in Canada’s film and television production sector, which has nearly doubled in the past decade. Although initially being hit hard by the collapse of production as Covid-19 public health restrictions kicked in early in 2020, over the last half of the year production returned to levels that fell just shy of the record high in the year prior.

- Rather than looking to historical approaches to broadcasting regulation, governments should heed experiences in communications regulation and antitrust to inform their policy responses to the network media challenges of today. These approaches take seriously the need for structural and conduct-based regulation of platforms, and potentially extend their public obligations to a wide range of issues central to the digital economy.

Ultimately, our goal is also to bring a wealth of historically- and theoretically-informed empirical evidence to bear on contentious claims about the media industries. Within a context where the role of policy and regulators looms large, knowing both the details and the broad sweep of the network media economy allows us to make informed contributions to the debate from an independent standpoint. This is essential given the ongoing Parliamentary and policy responses to recently concluded reviews of, for example, the Telecommunications and Broadcasting Acts, Copyright Modernization Act and the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) as well as initiatives now on the table with respect to the reform of the Broadcasting Act, news compensation and online harms.

This informed and independent view is also a key input to what could be considered the preeminent debate in this area of policy, the role of digital giants in the future of Canadian and global media markets. In fact, the tide has turned dramatically in the past few years to give rise to fundamental questions about whether the very business models and extraordinary market power of Internet giants such as Facebook and Google are inherently primed for nefarious possibilities, regardless of their owners’ best intentions to connect the world, are now on the table like never before. Consequently, in the last four to five years alone, there have been over one hundred public policy and/or regulatory examinations of the digital platforms worldwide, as governments from India and Australia to the European Union, the United States and Canada all grapple with the far-reaching implications of these new actors and their impacts on journalism, the media, economy and society (Winseck & Puppis, nd).1

Questions are also being raised about whether these entities have become too big to effectively govern—either through self-regulation or by existing democratic institutions. As a general principle, unless the rules shaping such companies’ conduct are guided by properly constituted legal and democratic oversight by parliaments, the courts, or administrative agencies—as was the case for the changes to the Canada Elections Act in late 2018—demands for the digital platforms to better govern themselves could make their “black box” character even more opaque than they already are. That Amazon, Facebook or Google could be broken up just like AT&T was in 1984 is no longer a far-fetched idea. In fact, such remedies are actively being considered in the US, UK, EU and Australia.2

We are fully supportive of concerns regarding the scale of these companies, their clout, and the threats that they pose to the Internet, some media, society and democracy. We are also fully supportive of the idea that new Internet regulations are needed for precisely these reasons. The issue is no longer if the platforms and Internet content will be regulated but when and how they will.3 Now even Facebook’s CEO, Mark Zuckerberg agrees that this is so and frequently reminds us that he has “repeatedly called for regulation . . . because I don’t think companies should be making so many of these decisions ourselves”.4

However, our analysis also suggests that claims that the Internet hypergiants’ fortunes are being made by cannibalizing the revenue that journalism and the music, movie, television and publishing industries need to survive should be met with a healthy dose of skepticism.5 There is also a need to be vigilant that the push for new Internet regulations does not just translate into harnessing the Internet-centric communications and media arrangements of today to protecting approaches to broadcasting regulation and cultural policy of the past. There is also ample reason for concern that the tough structural and conduct regulatory remedies needed to counteract problems of consolidation at every level of the communications, Internet and media ecosystem are being side-stepped by a one-dimensional focus on the global Internet giants. So, too, must the unlimited personal data harvesting models that fuel the commercial Internet services, and which are proving to be so corrosive of people’s trust, social relationships and democracy, be thoroughly addressed across the board and not just for the global Internet giants. Furthermore, all this needs to be done while avoiding the extreme tendency visible today directly regulate Internet content in a misguided gambit to solve all of society’s perceived ills by cleaning up so-called “harmful content” online.

To help understand this tangled knot of issues we need to better appraise where the Internet giants currently stand within Canada. And in so doing, our first question should be, these entities loom large, but how large and how do we know the answers to seemingly such simple but, in reality, very difficult questions?

Our data show that the US-based Internet giants are consolidating their dominance of digital advertising markets in Canada and becoming increasingly dominant across the advertising landscape as a whole. Indeed, the shift to the “mobile Internet” has helped Google and Facebook, in particular, to consolidate their lock on both online advertising and, increasingly, advertising spending across all media, as we will show later in this report. In addition, as the global Internet giants increasingly aggregate and distribute media and cultural content, existing media groups are becoming more platform-dependent, potentially jeopardizing their own economic, technological and cultural autonomy for uncertain benefits.6 All of this is critical to comprehending the bleak place in which many advertising-based media now stand.

However, while the growing clout of Internet hypergiants such as Google and Facebook is unmistakeable, it is a mistake to generalize from the digital duopoly’s dominance of the Internet advertising market to the $90 billion network media economy writ large. Treating developments in the advertising-based sectors as representative of the overall direction of the industry obscures the reality that these sectors constitute a small and receding aspect of the network media economy as a whole. Moreover, while the influence of the big five digital platforms—i.e. Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Microsoft, aka GAFAM—and Netflix is significant, within countries (Canada in particular) they are still outstripped by a large margin by the biggest national telecommunications and media groups, as this and the next report in this series will show.

Ultimately, the media’s place in the economy, society and our everyday lives is changing dramatically and is currently up for grabs in ways seldom seen. Some communication historians call times like these a “critical juncture” (McChesney), or a “constitutive moment” (Starr), when decisions made will become embedded in technology, markets and institutions, and then press down on us, for perhaps a century or more if the lessons of “the industrial media age” offer any guide to the contemporary debates surrounding the “Internet” or “digital media age”. The CMCR Project does its best to engage with such realities in a bid to help secure the communication and media that we need and deserve.

- Last year, in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic, revenue across the network media economy stayed roughly the same as a year earlier, i.e. $90 billion. While online video and music services, digital games and online advertising (i.e. digital media sectors) as well as Internet access services continued to grow, all other sectors of the media economy suffered setbacks last year, some very substantial.

- Last year’s setback, however, appears to have only been temporary, with most sectors bouncing back since. Over the long run, the media economy has more than quadrupled in size.

- Even mobile wireless services stumbled for the very first time, as estimated revenue slid from $29.2 billion to $28.1 billion, last year. This loss was due in part to Covid, because lucrative international roaming charges disappeared as travel across borders ground to halt. In addition, however, ongoing albeit modest improvements in competition in many provinces have also put steady downward pressure on mobile data prices and overage charges.

- Internet access services continued to grow briskly, as revenues rose by a billion dollars to $13.9 year-over-year. This underscored the importance of broadband access as people increasing turned to the Internet for work, to go to school, obtain government services and socialize with others.

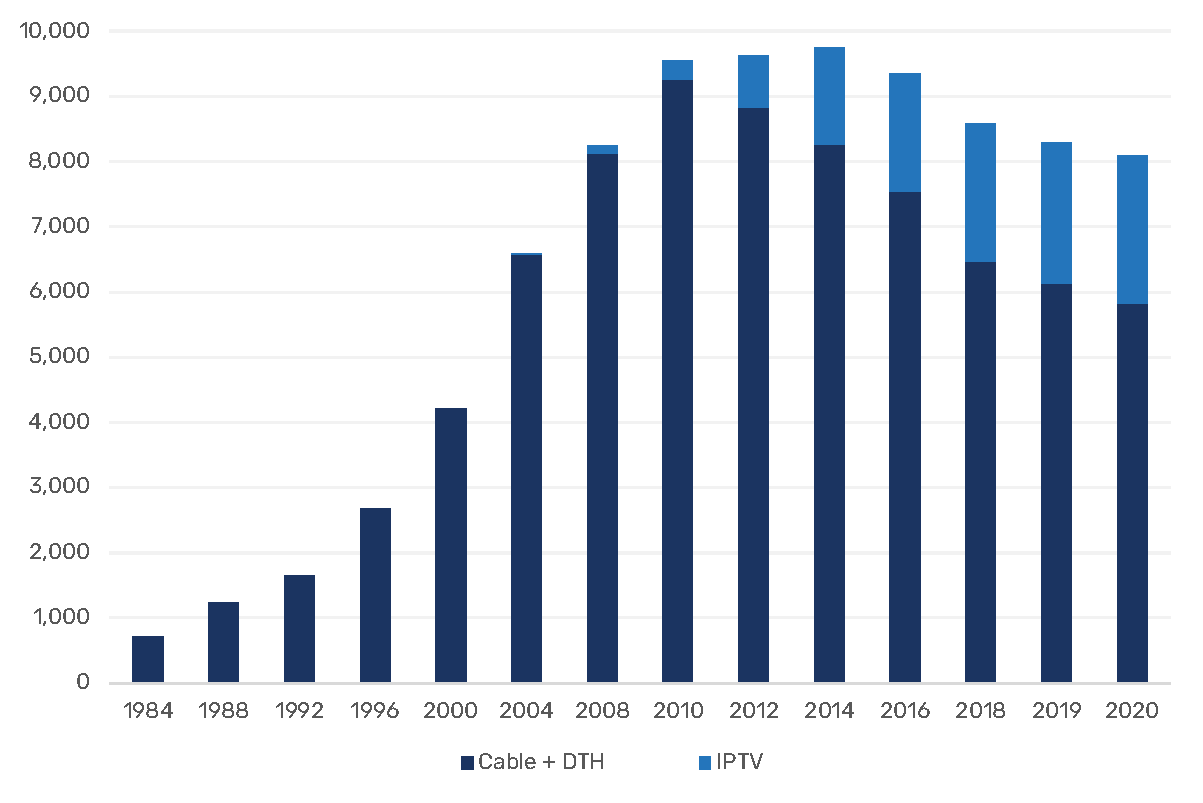

- Revenue for cable, IPTV and satellite TV declined from $8.3 billion to $8.1 billion over the year and household subscriber levels fell just below 70% last year—a significant drop from the year before, when 73.6% of Canadian households had one such subscription.

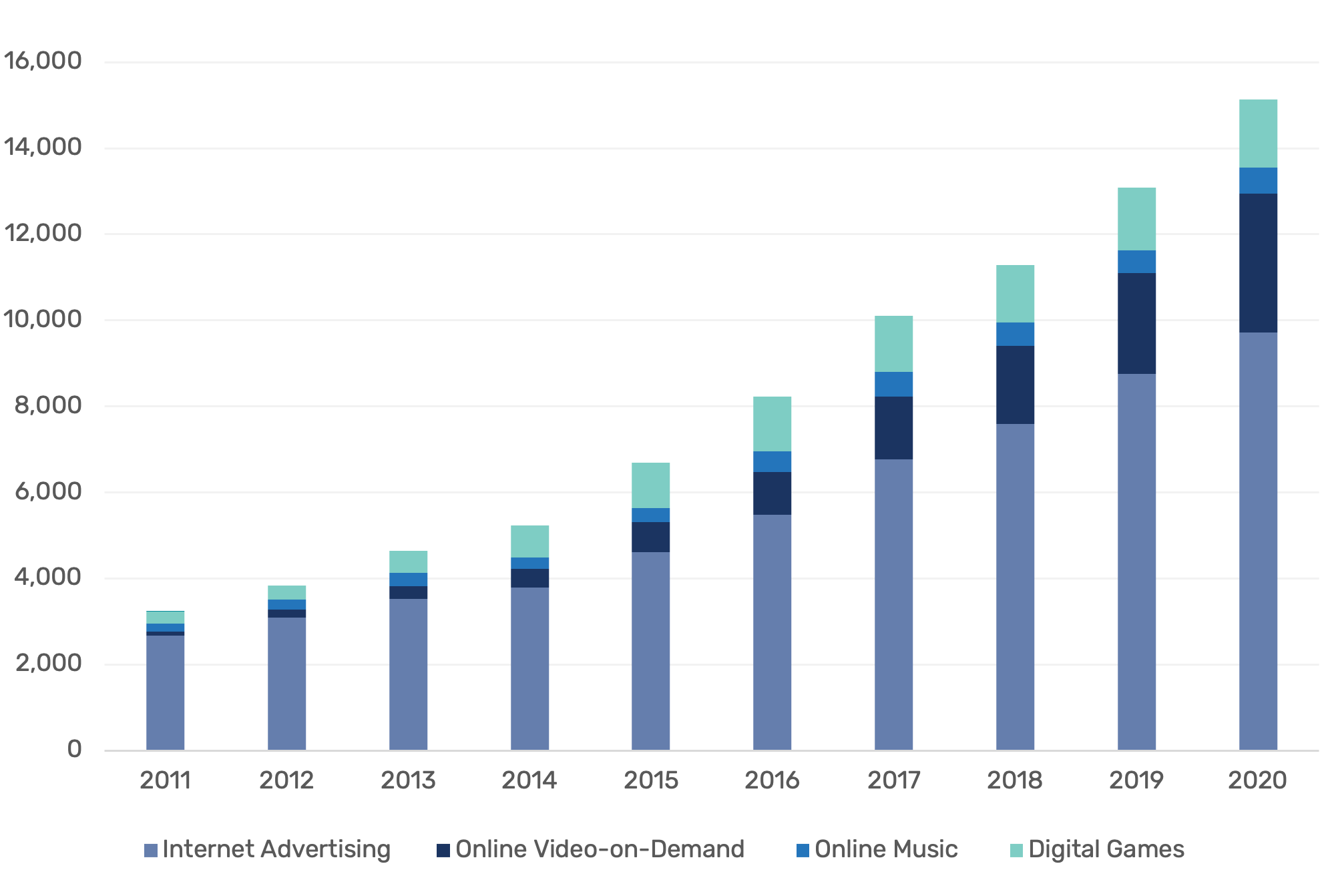

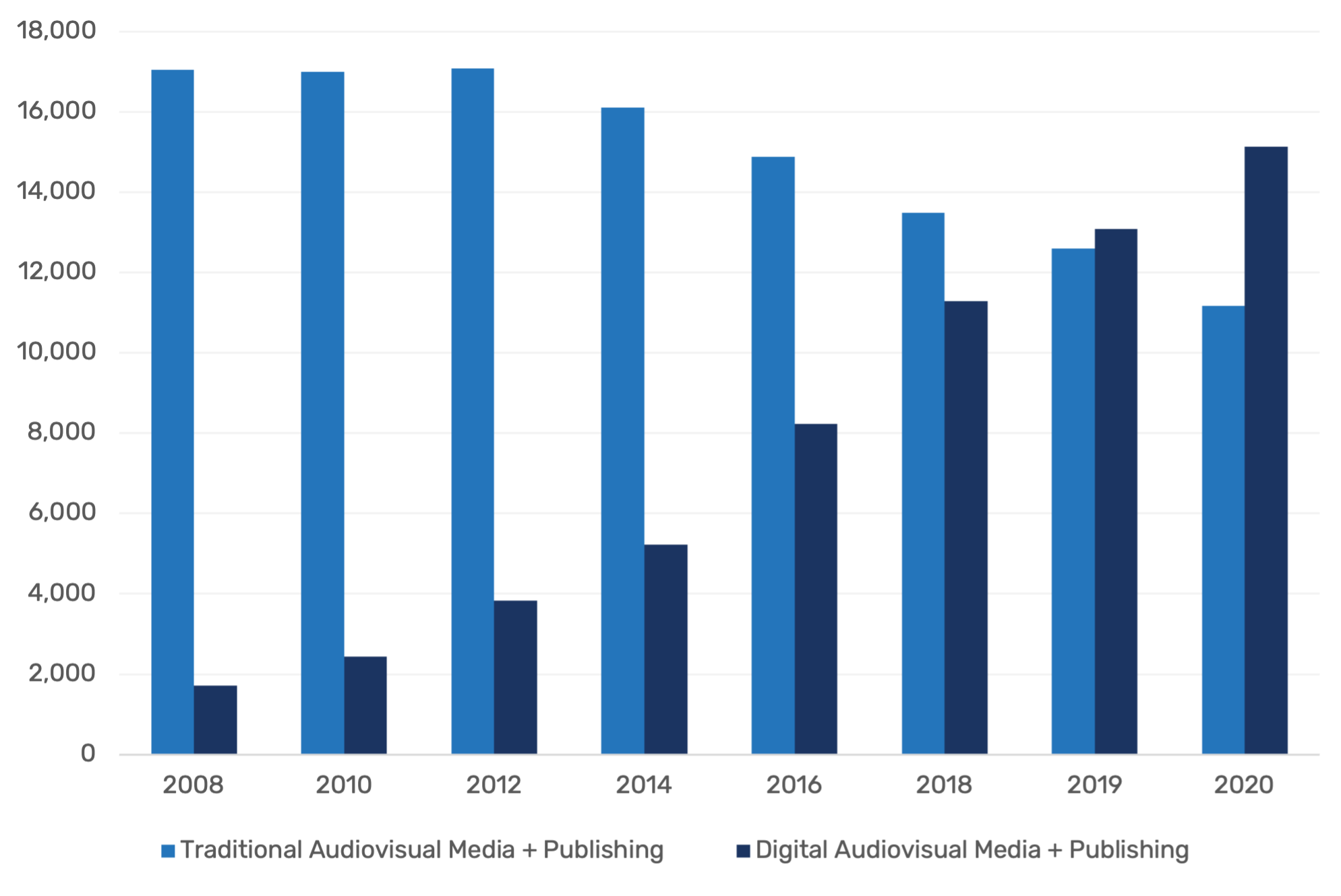

- In contrast, however, revenue for digital audiovisual media services (AVMS)—online video, music, gaming and app stores—continued to soar last year to over $5.4 billion. So, too, did revenue for Internet advertising, which rose from $8.8 billion to $9.7 billion over the year. Add all the digital AVM sectors together, and total revenue reached $15.1 billion, up from $13.1 billion a year earlier. These sectors are now defining features of the network media economy and accounted for nearly 1/5th of all revenue (17%) in 2020. These sectors also seemed to be “pandemic proof”.

- As a result of these developments, global actors like Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Netflix (the so-called GAFAM+ group of Internet giants) have become significant figures on the media landscape in Canada. Combined, they had an estimated $10.9 billion in revenue last year from their Canadian operations, up from $9.4 billion the previous year.

- While GAFAM+ group’s combined market share was 12% last year, it is essential to bear in mind that the “big 5” domestic companies in Canada still accounted for 70% of the network media economy last year: Bell, Telus, Rogers, Shaw (Corus) and Quebecor.

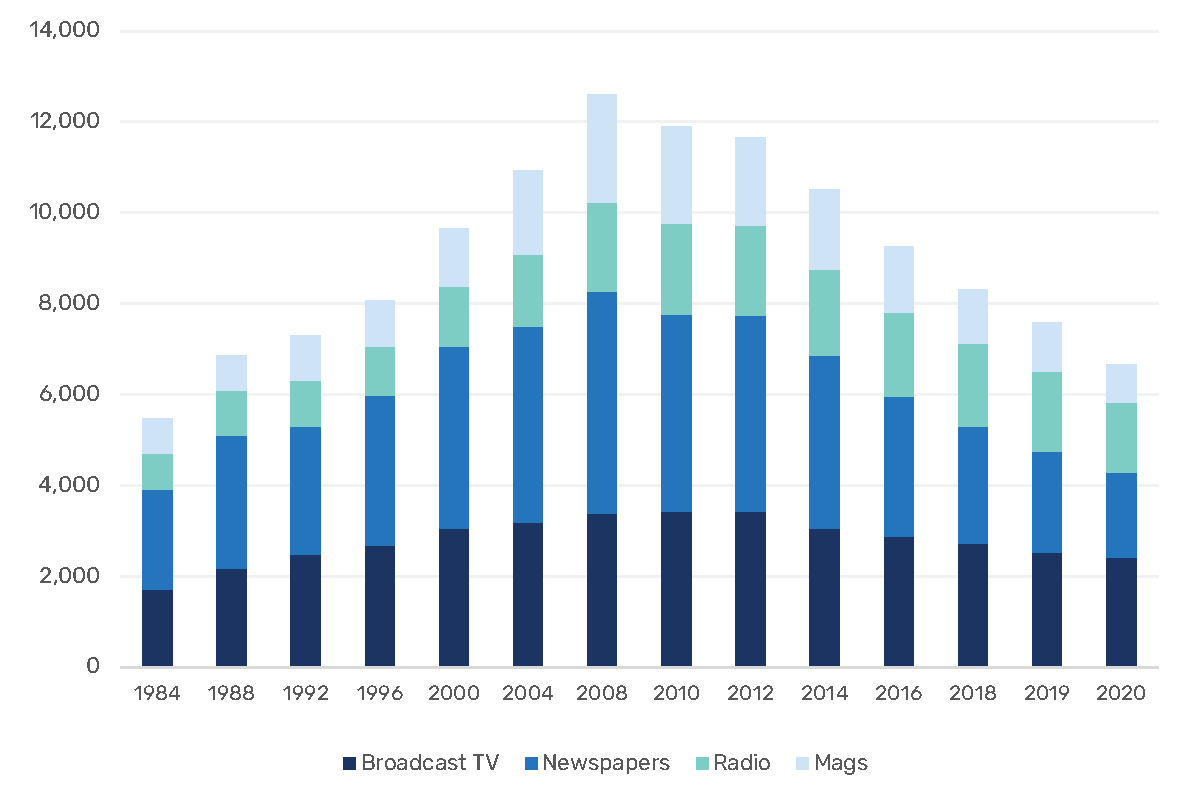

- Total advertising spending across the media economy dropped 300 million dollars last year, from $15.5 billion in 2019. Four advertising-dependent media sectors are in crisis on account of the long-term stagnation and, on some measures, decline in advertising revenue: broadcast television, radio, newspapers and magazines. Collectively, they have lost close to $6 billion since 2008 and their combined revenue now is half what it was then. It is fashionable to blame Google and Facebook’s for this state-of-affairs, but such charges are too simplistic, for reasons we show in this report.

- There is no generalized media crisis. Most media sectors are vibrant and thriving. This applies to the digital AVM services sectors and, specifically, to the TV marketplace overall, with the addition new pay TV sectors over time, including online video services, driving total TV revenues (i.e. broadcast TV, pay & specialty TV and online video) to $9.6 billion in 2020.

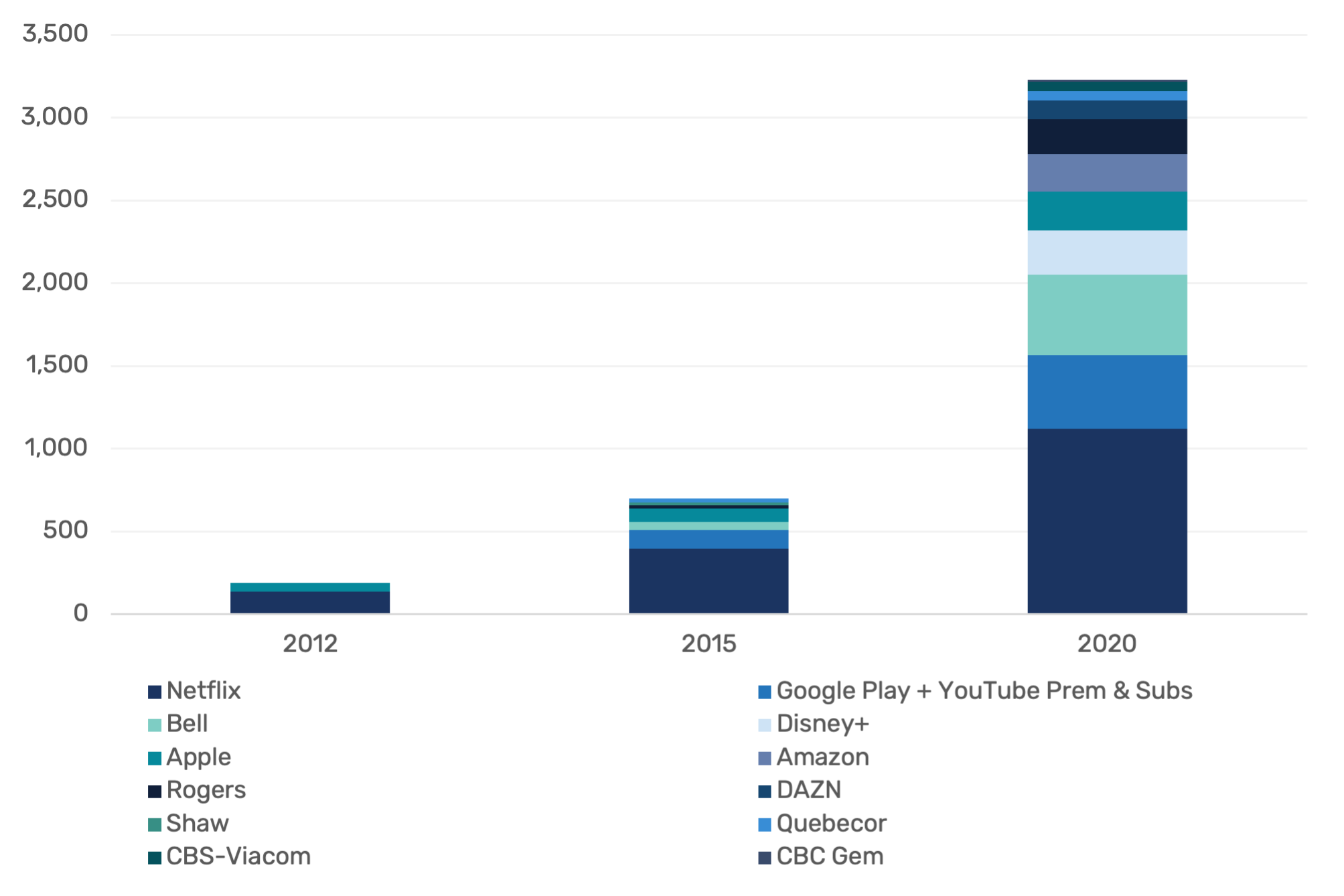

- Netflix had 7.2 million subscribers (just under one-half of all households in Canada) and $1.1 billion in revenue last year. Estimated revenue for online video services reached $3.2 billion last year—a nearly twenty percent rise over the previous year but a growth rate that now appears to be slowing relative to past trends.

- Film and TV production was slammed by the onset of Covid-19 public health restrictions in the first half of the year, but recovered thereafter with $9.3 billion in investment in 2020—just shy of the all-time record a year earlier.

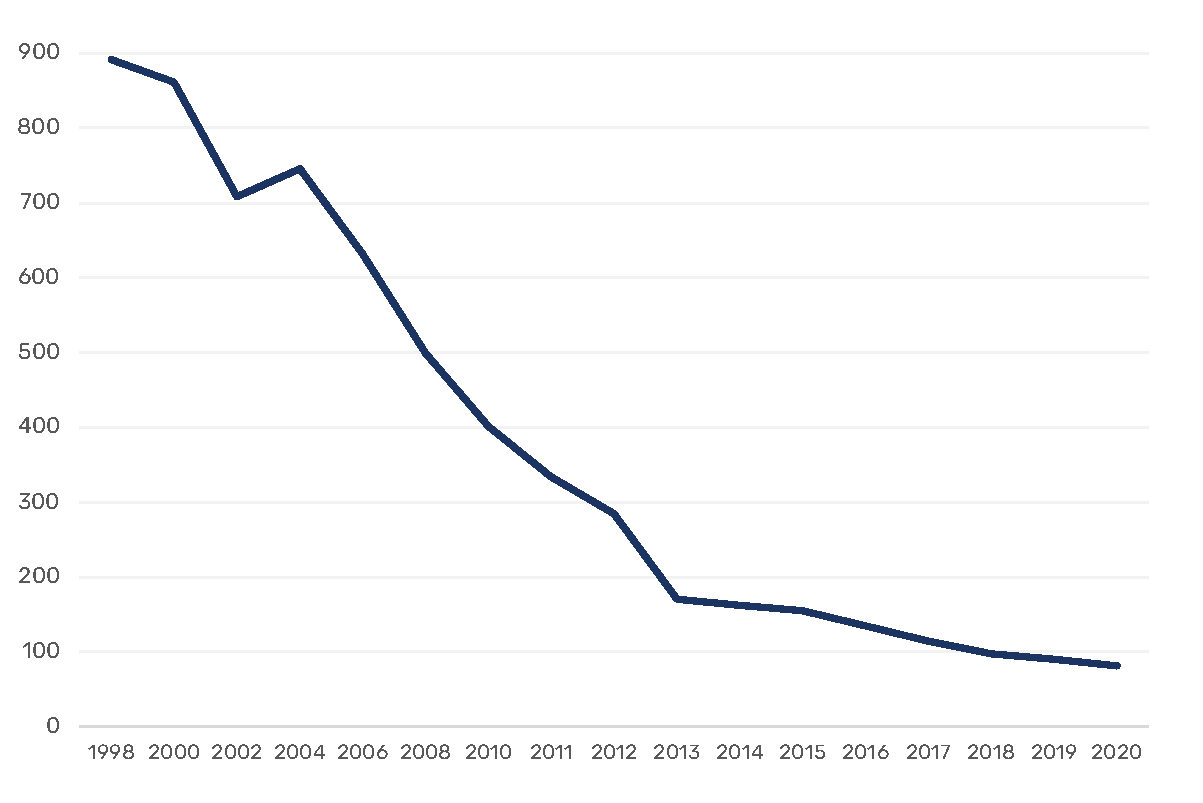

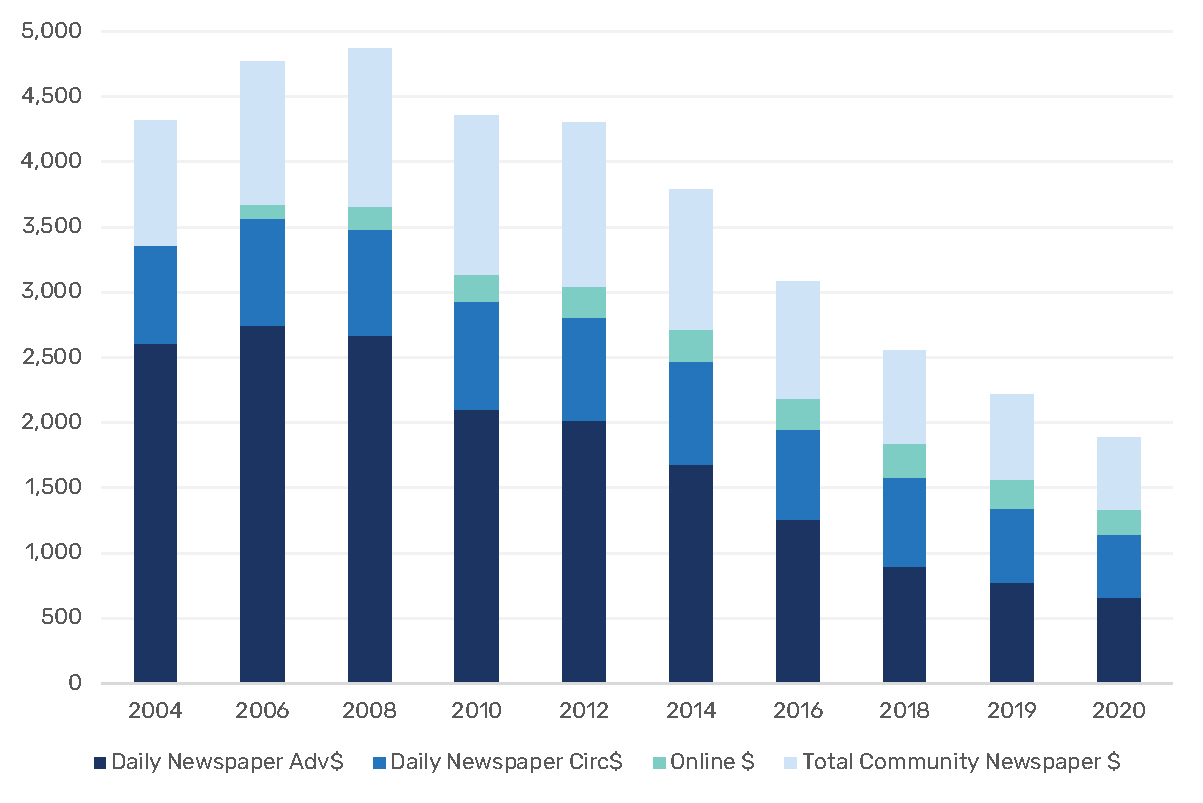

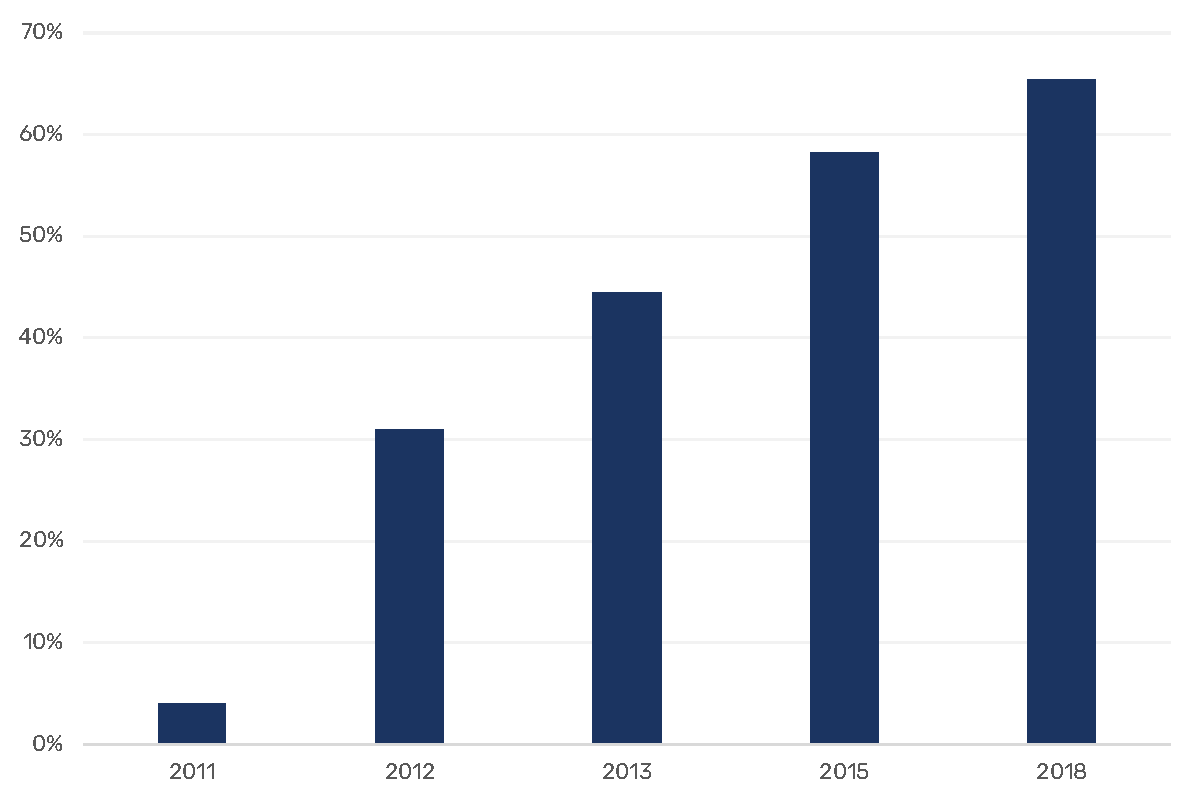

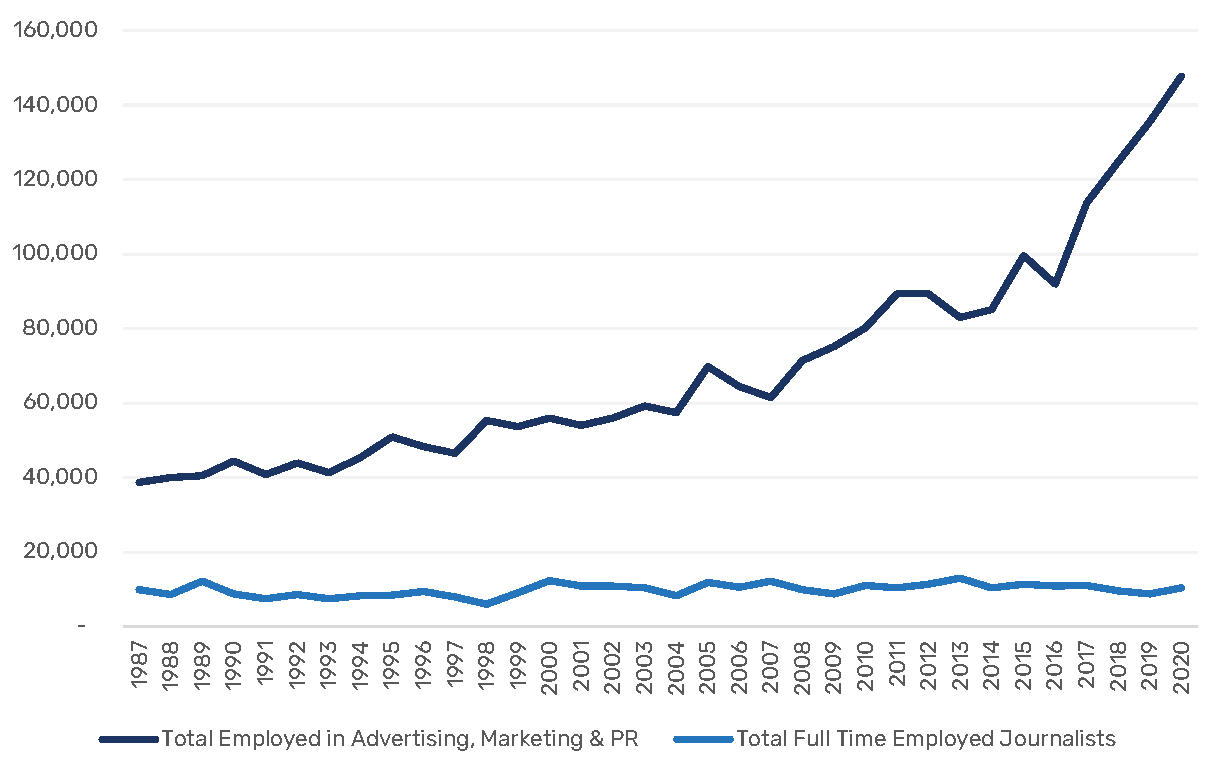

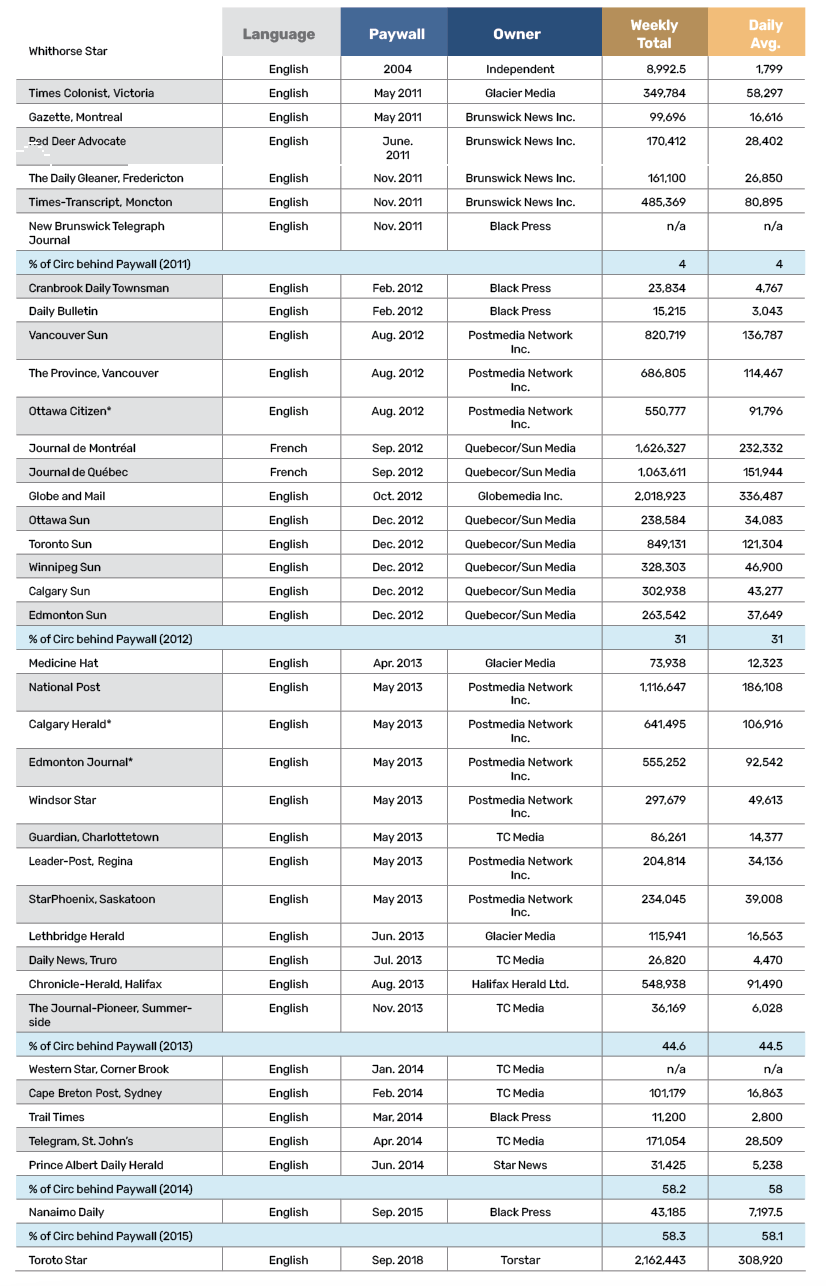

- Newspapers are in turmoil with revenue plunging from a high of $4.9 billion in 2008 to $1.9 billion last year and the number of full-time journalists dropping from 13,000 in 2013 to 10,500 last year. These dismal trends continued unabated even as news organizations took advantage of subsidies from the federal government’s $595 million (over five years) Journalism Support Program and as the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy program also offered some relief during the pandemic. While independent journalism continues to flounder, the ranks of public relations, advertising and marketing professionals have swelled enormously; by 2020, they outnumbered journalists 14:1.

- The story is not entirely bleak, however, with some new news, information and public commentary sources filling in some of the gaps created by the collapse of traditional journalism, e.g. National Observer, Canadaland, The Tyee, etc.

Our 2020 annual series of reports on the state of the telecoms, Internet and media industries in Canada marks a decade since we began this effort. The first report in our annual, two-part series examines the development of the media economy since 1984, with the “media” defined broadly to include data for twenty different sectors grouped into three categories, as depicted in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1: Key Sectors of the Network Media Economy in Canada, 2020

Ultimately, we combine all of these separate sectors together to get a bird’s-eye view of the network media economy. We call this the scaffolding approach. The aim of this approach—and this report—is to get the best sense we can of how all the different sectors of the telecoms-Internet and media industries have developed over time, to understand the scale and pace of the changes that are taking place, and to see how all of the sectors that we cover fit together to form “the network media economy”.

To this end, our approach begins by assembling a multisectoral body of data for the telecoms and Internet access, audio-visual media services and core Internet applications listed in Figure 1 above that collectively comprise “the network media economy”. The objective is also to determine which of these media sectors are growing, stagnating or in decline, while also highlighting those that have discovered renewed paths to growth, such as the music industry. To this end, the report pays close attention to, for instance, whether online audiovisual media services such as Netflix, Amazon Prime Video and Crave, and online gaming, apps and app stores (digital games), are cannibalizing established media or helping to expand the size and diversity of the media economy. Other trends such as cord-cutting and cord-shaving are also examined.

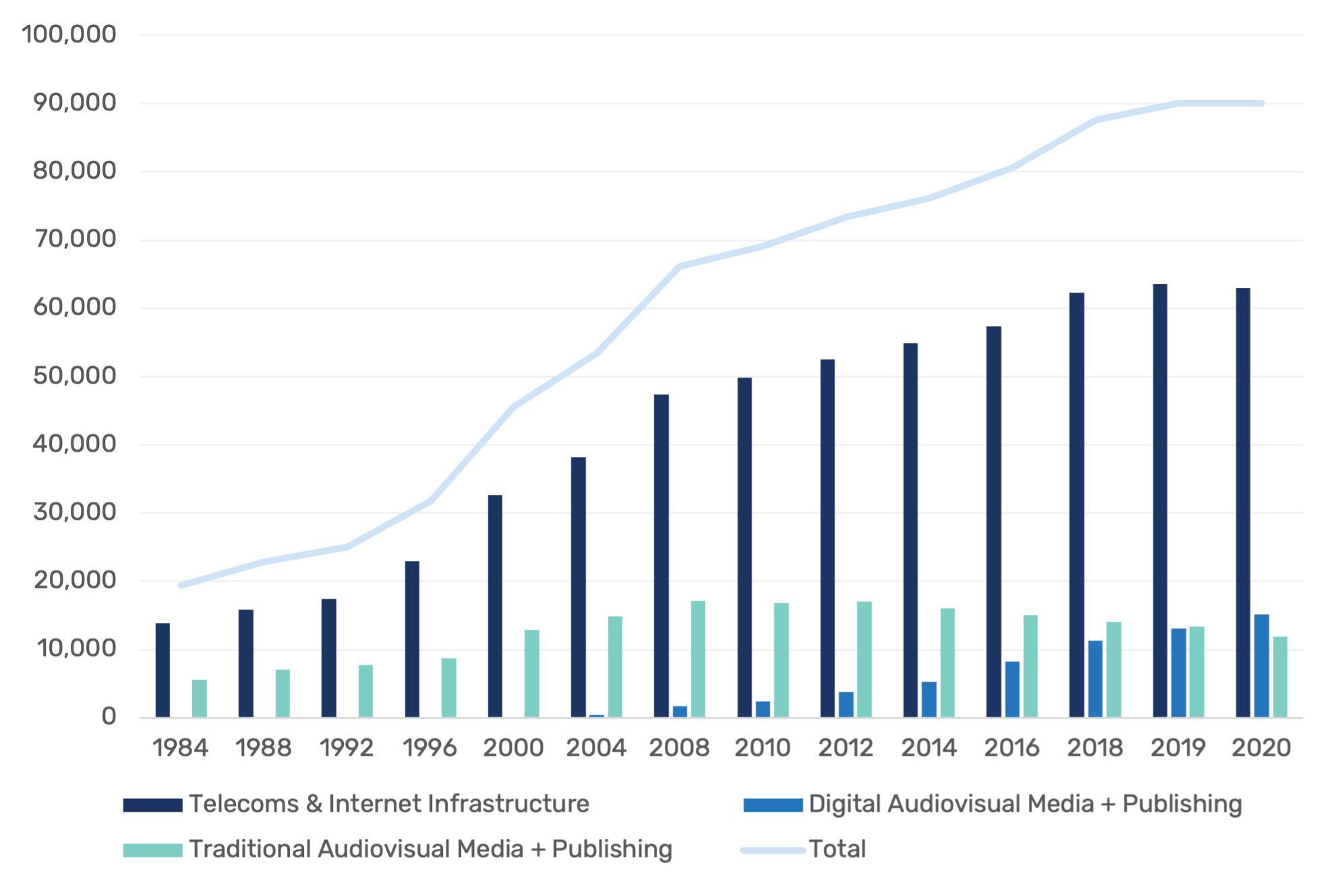

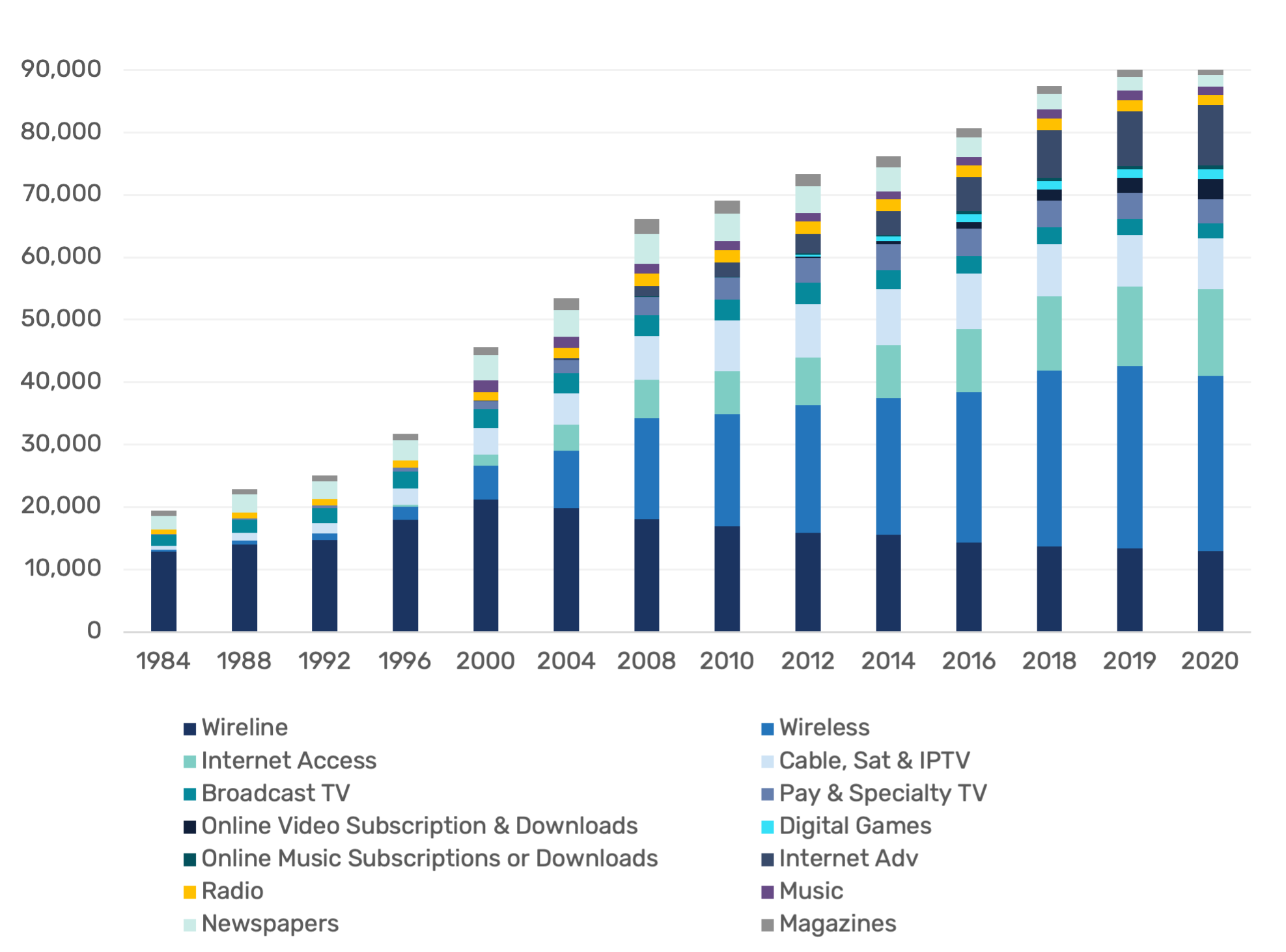

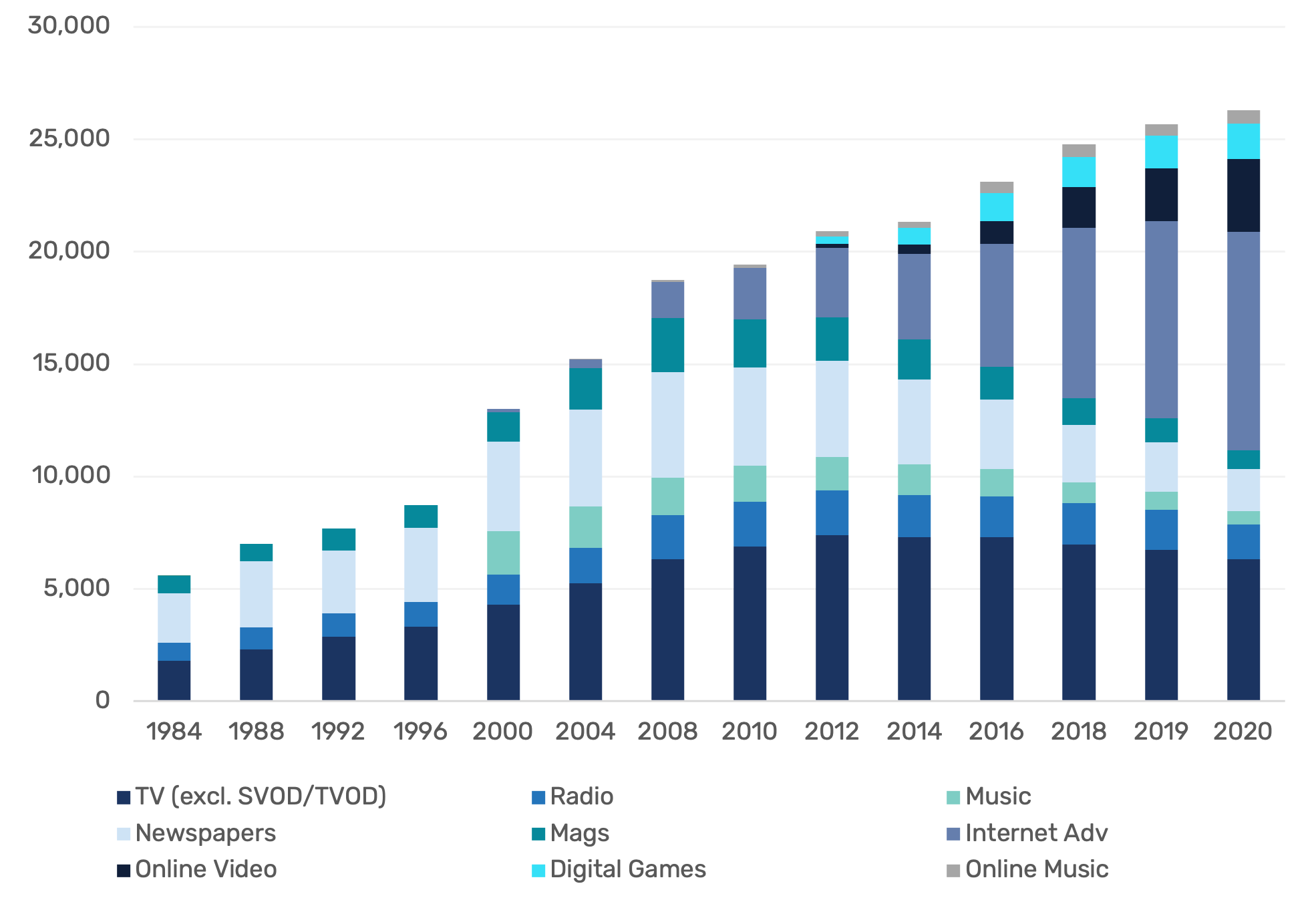

Since the early 1980s when our coverage for this report starts, the rise of entirely new media sectors–e.g. mobile wireless, Internet access, pay and specialty TV, digital AVMS, and so forth—has added immensely to the size and complexity of the media economy. Over this period, total revenue for the network media economy in Canada more than quadrupled from $19.4 billion in 1984 to $90 billion last year. That said, last year the media economy was an exception; slammed by the Covid-19 pandemic, revenue across the board stalled relative to the previous year.

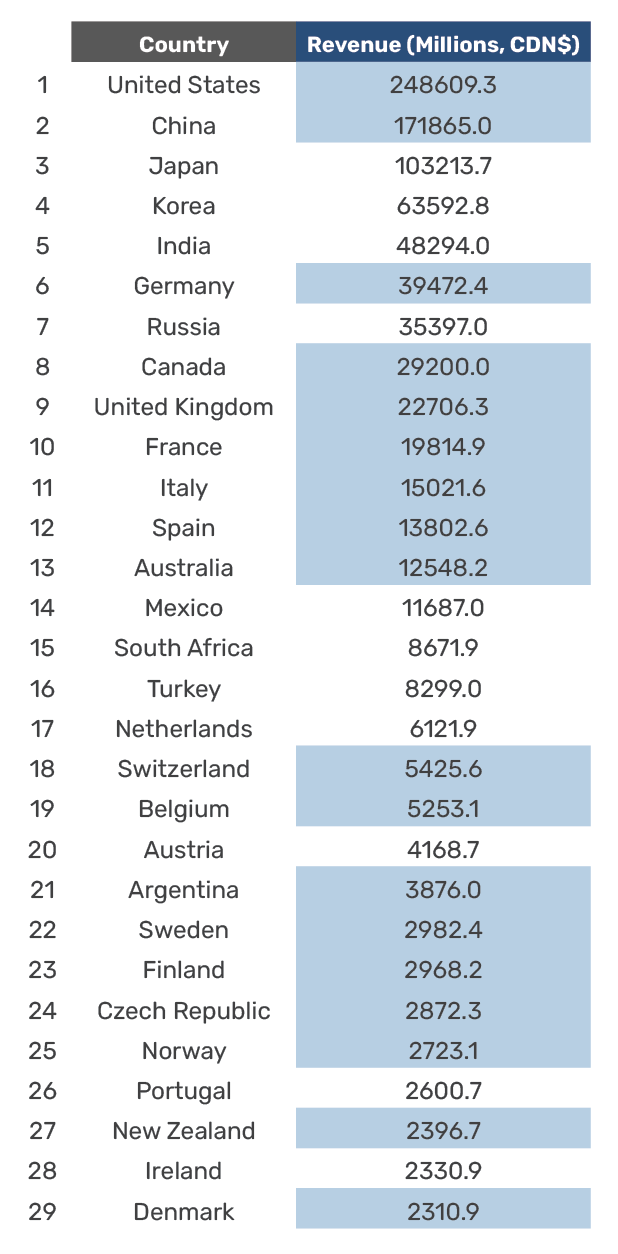

In contrast to those who claim that the media economy in this country is a pygmy amongst giants especially relative to the United States, it is important to highlight the fact that of the thirty countries examined in Who Owns the World’s Media, the sum total of which account for roughly 90% of the world’s media revenues, Canada ranked as having the 9th largest media economy (Noam, 2016, pp. 1018-19).

Figure 2 below illustrates the immense growth and transformations of the network media economy in Canada that has taken place over the past thirty-six years.

Figure 2: Development of Telecom & Internet Access Services vs Digital and Traditional Audiovisual Media, 1984-2020 (current $, millions)

Source: see the “Total Revenue” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

While all segments of the media economy have grown substantially over the long-run, there are several trends and unique differences among them that merit closer attention. A key development identified in this report, for instance, is the fact that revenue for most communication, Internet and media sectors flat-lined or fell last year.

We also continue our previous work highlighting how media that have historically relied primarily on advertising revenue as the core of their business models continue to be caught between the pincers of stagnating, or by some measures, falling, advertising revenue while simultaneously facing the rapid rise Google and Facebook and those two companies’ fast-consolidating grip, not just on online advertising, but ad spending across all media. In this regard, four specific media sectors appear to be in terminal decline: broadcast television, radio, newspapers and magazines. Collectively, their revenue has collapsed; last year it was roughly a half what it was in 2008, when their fortunes went into tailspin from which they have never recovered (and probably won’t).

That said, there is no general crisis of the media. This is because advertising-funded media have been steadily eclipsed by the telecoms and Internet access sectors as well as “pay-per” audiovisual media services.1

Thus, while there is no doubt that advertising is and will continue to be an important part of the media economy, it only underpins a relatively small and steadily receding subset of the media. Altogether, advertising-funded media account for a modest 17% ($15.2 billion) of the $90 billion media economy.

The real centre of the network media economy consists of the communications and Internet access segments, i.e. the pipes, bandwidth, and spectrum-based –connections that are now central to effective participation in society, the economy and daily life. In 2020, they had total combined revenues of $63 billion, or 70% of all revenue generated within the network media economy, compared to the $15.2 billion in advertising-spending across all media. These sectors have grown far more quickly than others and are vastly larger than the content side of the media, although collective revenue for these sectors also fell by three-quarters of a billion dollars (a loss of 1.2%) last year as well as people cut their cable connections and pared back spending on mobile data services, including roaming fees as international travel ground to a halt.

Adding to the shift away from ad-supported media, and displaying remarkable resiliency even amidst the pandemic, the combined revenue for online video, music, digital games and app stores continued to rise last year to $5.4 billion, up by a billion dollars (or 25%) from the previous year. This was in keeping with the fast-paced growth of these sectors over the last decade.

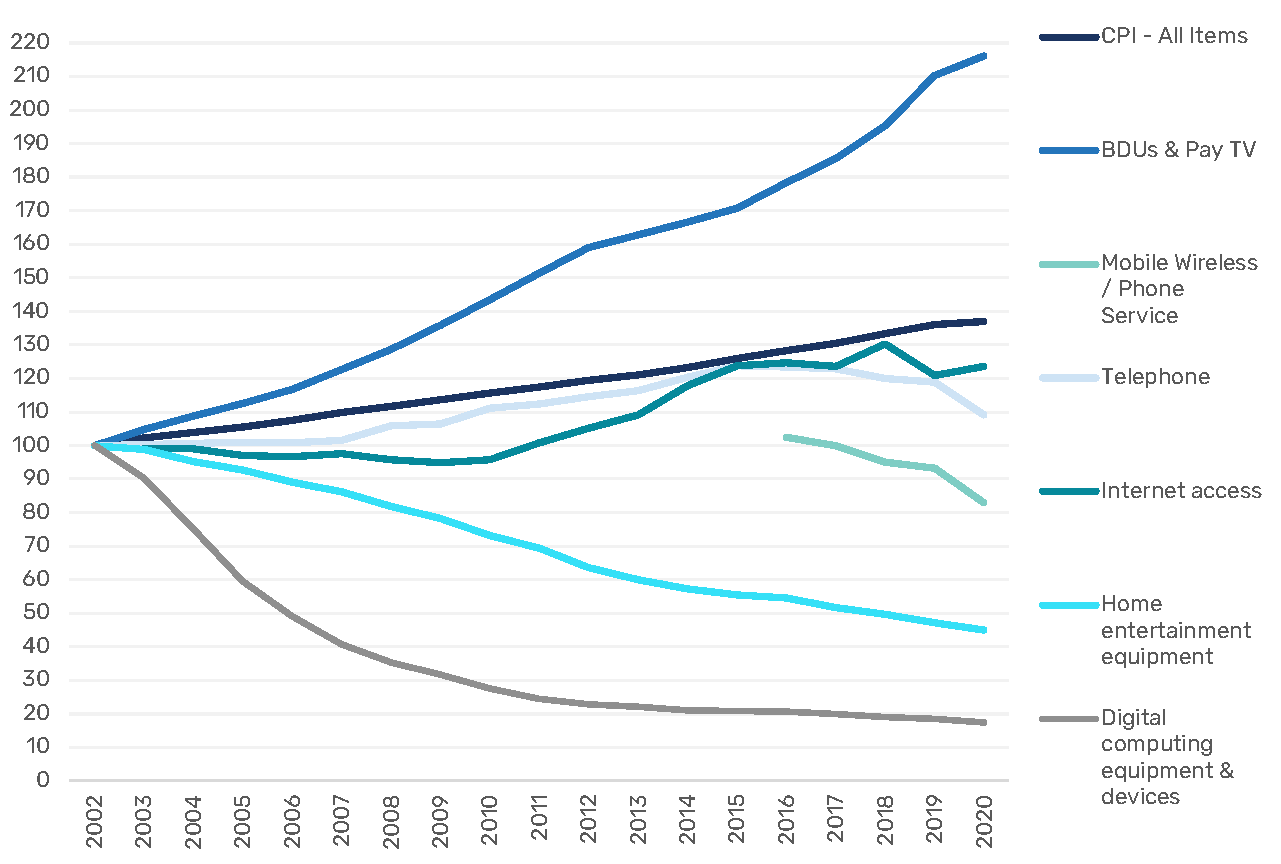

In fact, combined revenue for communications and internet access services as well as subscription-based digital AVM services have come to outstrip that of advertising-funded media, including Internet advertising, by a five-to-one ratio. The upshot of these developments is that, in an increasingly Internet- and mobile wireless-centric world, it is network connectivity and subscriber fees, not advertising-supported media, that are king (see Odlyzko).

We also see this in household spending. In fact, such spending on communication services such as broadband Internet access and mobile wireless services as a percentage of all household outlays has doubled over the last four decades, while the percentage of income that households spend on media content, cultural goods and live entertainment services has stayed remarkably stable at an average of 1.3%, despite the advent of a vastly more complex and diverse array of such services. At the same time, spending on media, information and communication technology, in contrast, has fallen over time because even though people are buying more such equipment, the cost of such technology has plunged over time.2

Figure 3 below illustrates the point.

Figure 3: Household Spending on Communications and Media Services and ICTs, 1982-2020

Sources and note: Statistics Canada (2021). Table 203-0021 Survey of household spending (SHS), household spending, Canada, regions and provinces. See “Household Spending” sheet in Excel Workbook.3

The upshot of this is that enterprises providing media, entertainment and culture services are battling one another for a bigger slice of a relatively fixed pie. This phenomenon where household spending on such services stays fixed over such a long period of time has been called the “law of relatively constant media expenditures” by observers from a wide array of theoretical and political positions. It is compounded by the fact that much the same phenomenon applies to total advertising spending across all media, as this report shows in the pages ahead.4

What this means in practice is that different segments of the communication, Internet and media industries have distinctive characteristics and follow different evolutionary paths. this is one more reason why we need to rely on the scaffolding approach just outlined, i.e. because using this method helps to shed light on these distinctive characteristics and the different development paths of different media over time.

Figure 4 below depicts each sector covered in this report and its evolution over time separately in order to reveal the specific details and broad trends being introduced here and that we will return to over the course of the following pages in this report. The basic message of Figure 4 is this: while all areas of the telecoms-Internet and media industries have grown substantially over the long-run, and changes have been especially fast moving with respect to the digital AVMS sectors in the last five or six years, there are also unique differences among all of them that merit closer attention.

Figure 4: Separate Media, Distinct Evolutionary Paths and the Network Media Economy, 1984–2020 (current $, millions)

Source: see the “Total Revenue” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

To be sure, communication and media companies in Canada are facing intensifying competition with Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Microsoft (the so-called GAFAM group of Internet giants) as well as Netflix as the latter move ever more deeply into media content and entertainment services sectors in Canada. In addition, as the Internet companies take on a growing role in the aggregation and distribution of media content, existing media groups are becoming more platform-dependent, at the risk of jeopardizing their own economic and cultural autonomy—and for uncertain benefits.5 Ultimately, these firms are all battling one another over a relatively “fixed pie”, given the remarkable stability of household spending on media, cultural and entertainment services, as observed above. The upshot is that the competition between these companies is intense, and becoming more so, even if the markets they operate in are still highly concentrated.

These developments have ignited fierce debates over the impact of GAFAM on the media in Canada— as well as other countries around the world—and are a key driver of calls for aggressive new forms of digital platform regulation that would have been unfathomable just a few years ago. They have also re-ignited long dormant debates over cultural nationalism and technological sovereignty that have not been seen with such intensity since the 1970s and 1980s. While these debates, regrettably, tend to be reduced to simplistic, ideologically-driven binaries between cultural nationalists, lobbyists and think tanks joined at the hip with domestic communication and media conglomerates on the one side versus free and open Internet advocates whose views, wittingly or not, line up with the interests of GAFAM, on the other, the fact of the matter is that reality and potential solutions to the intractable issues now before us are more complex than either of those positions allow. The rigidity, indeed, orthodoxy on both sides is stultifying and frustrating.

These concerns have been coming to head in the last few years as scholars and policymakers around the world intensely scrutinize a litany of problematic practices arising from the growth of the tech giants. These include: the rise of platform power and “digital dominance”; potential threats to domestic media and cultures; privacy and data protection; “fake news” and hate speech; national sovereignty; the integrity of elections; and antitrust. Consequently, governments from India and Australia to the Netherlands and Canada are all grappling with the implications of these developments. Indeed, there have been over 100 such public policy examinations in the last five years alone, as ongoing tally of these inquiries chronicles.6

The aim of this report and the next—and all of our work—is to bring out the greater complexity behind the issues at stake. It is also to provide a fairly systematic and long-term body of independent analysis that we hope others will draw to inform their positions.

Anchor Findings

• Mobile wireless and Internet access services continue to grow at a brisk pace, but Canada’s struggle to meet its targets for universal, affordable broadband internet access continues to be a significant issue.

• Canada’s adoption of IPTV is high relative to other countries, but it severely lags international peers in “fibre to the premises” access, the gold standard for communications infrastructure.

• Following favourable regulatory outcomes related to minimum service standard and net neutrality in the mid-2010s, a change in CRTC leadership since 2017 has put the future of broadband regulation and even the legitimacy of the agency itself into jeopardy.

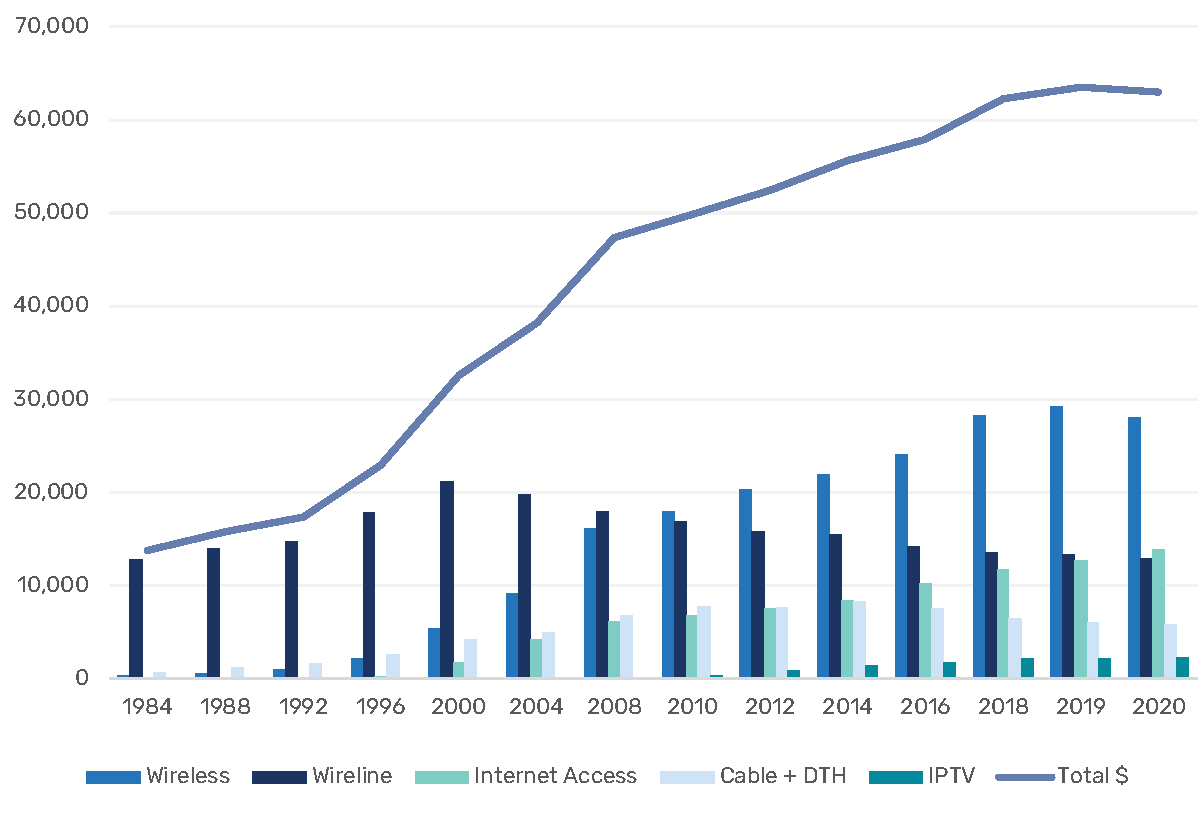

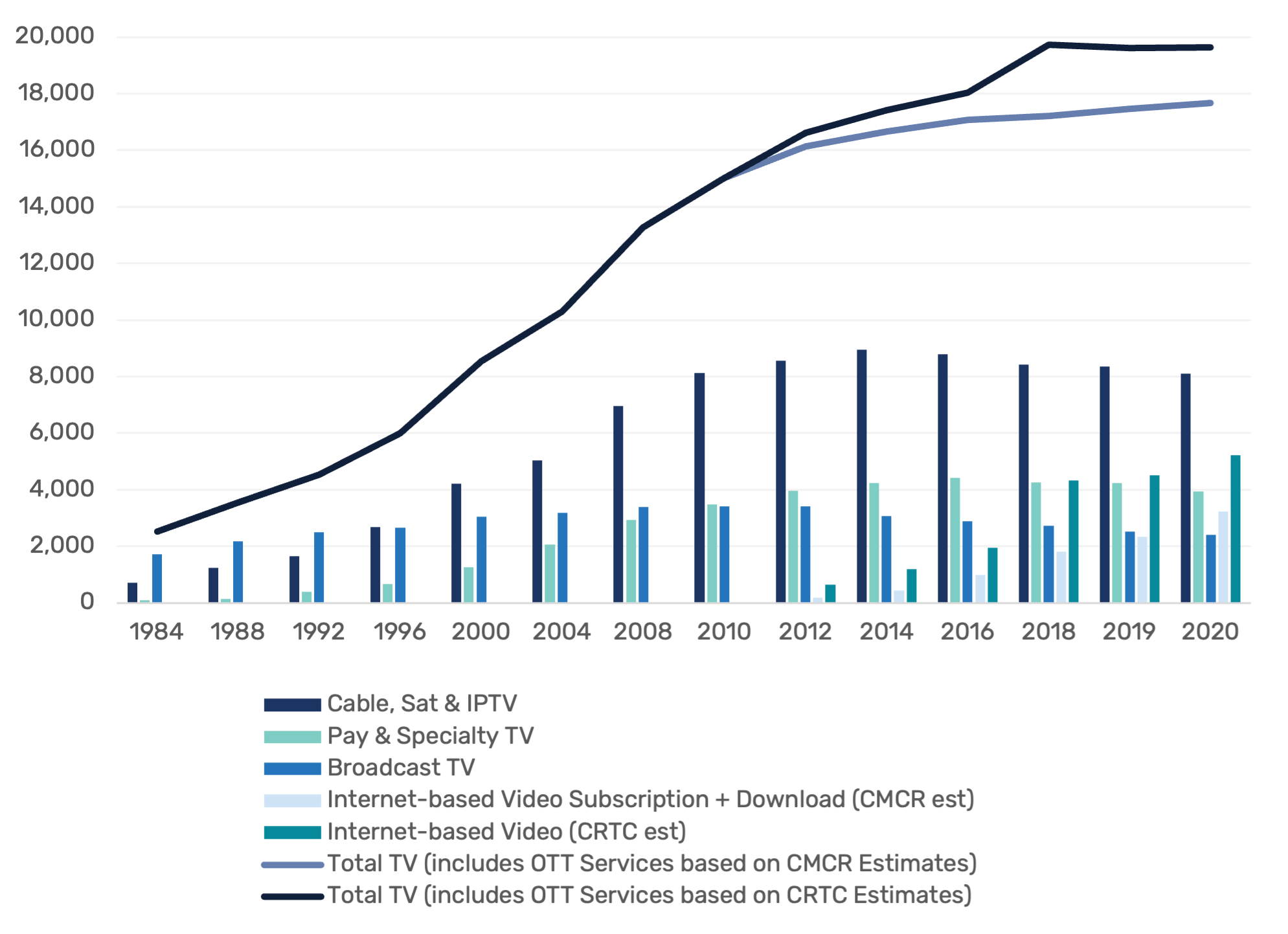

The telecoms and Internet access industries have grown enormously, from $13.1 billion in 1984 to $63 billion last year. They account for approximately 70% of all revenue, and are thus the fulcrum upon which the media economy pivots. Figure 5 illustrates their development over time.

Figure 5: Revenues for the Telecoms and Internet Infrastructure Sectors, 1984-2020 (current $, millions)

Source: see the “Wireline”, “Wireless”, “ISP” and “Cable DTH IPTV” sheets in the Excel Workbook.

Up until last year, mobile wireless services have grown tremendously since their introduction to Canada in the early 1980’s. Although they began as luxuries or business tools, the market for these services expanded quickly following the turn-of-the-21st century to become a cornerstone of the digital media ecology. Revenues from mobile wireless services overtook plain old wireline telephone services in 2009, while in 2014 the number of Canadian households subscribing exclusively to mobile services for their voice calling needs exceeded those relying exclusively on landlines for the first time (CRTC, 2015, p. 1). The centrality of mobile wireless services is also underscored by the fact that they are now the largest sector of the network media economy, by far, with revenue having grown more than five-fold from $5.4 billion in 2000 to an estimated $28.1 billion last year.

It is noteworthy that 2020 was the first year we have measured when mobile sector revenue shrunk—it was down roughly $1.1 billion from its high of $29.2 billion in 2019. This decline is likely the result of the global COVID-19 pandemic, as major operators suspended overage fees and saw international roaming fees grind to a halt overnight at the beginning of 2020. To a certain degree, it is to be expected that industry revenues will recover swiftly as the pandemic abates, especially with the rollout of 5G networks already underway, a development which sets the incumbent network operators up nicely to capture revenue from an expanding scope of customers and service applications.

It is also worth noting, however, that the revenue declines in this sector were specific to Bell, Rogers, and Telus—the three national incumbent providers—while the regional competitors Videotron, Freedom Mobile, Sasktel, Tbaytel, and Eastlink each continued to achieve revenue growth. The possibility should not be discounted that the competitive pressure brought to the markets in which regional providers operate is having an impact on the incumbents’ bottom lines. Whether or not this is the case could become more clear as life returns to normal (i.e. travel resumes, Covid relief measures are rolled back, etc), although the looming merger between Rogers and Shaw will certainly complicate the situation looking forward.

It is also worth observing that Canada mobile wireless market is the 8th largest in the world, based on revenue, as Figure 6 depicts.

Figure 6: Mobile Wireless Markets in the OECD, EU and Other Select Countries Ranked by Revenue (Millions, CDN$)

Source and Note: see “Biggest Mobile Wireless Markets” sheet in Excel Workbook. 2020 data = no highlight; 2019 data = light green shading.

The growth of mobile wireless services has tracked an expanding array of devices that people use to connect to mobile wireless networks—a sector that once primarily connected “feature phones” and pagers now provides connectivity to a constantly expanding range of different smartphones, tablets, and connected laptop PCs. As providers begin to debut “5G” networks, it is expected that this array will continue to expand in both scale and scope, with the emphasis shifting even further in the direction of data-based services, rather than the traditional voice-based services that gave mobile services their start. Consistent with this trend, mobile data traffic has roughly doubled (40-60% growth) in Canada each year over the past decade. Cisco projects that mobile data traffic will grow four-fold between 2017 and 2022.

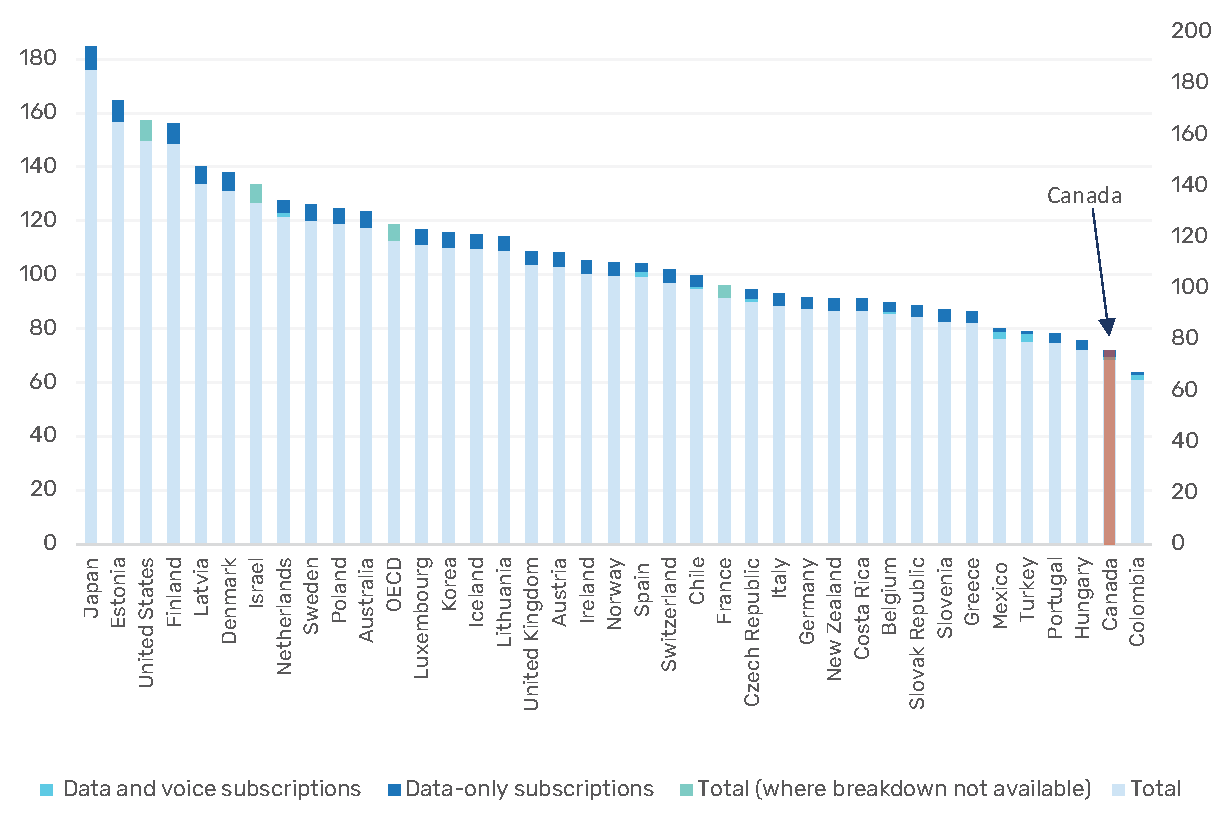

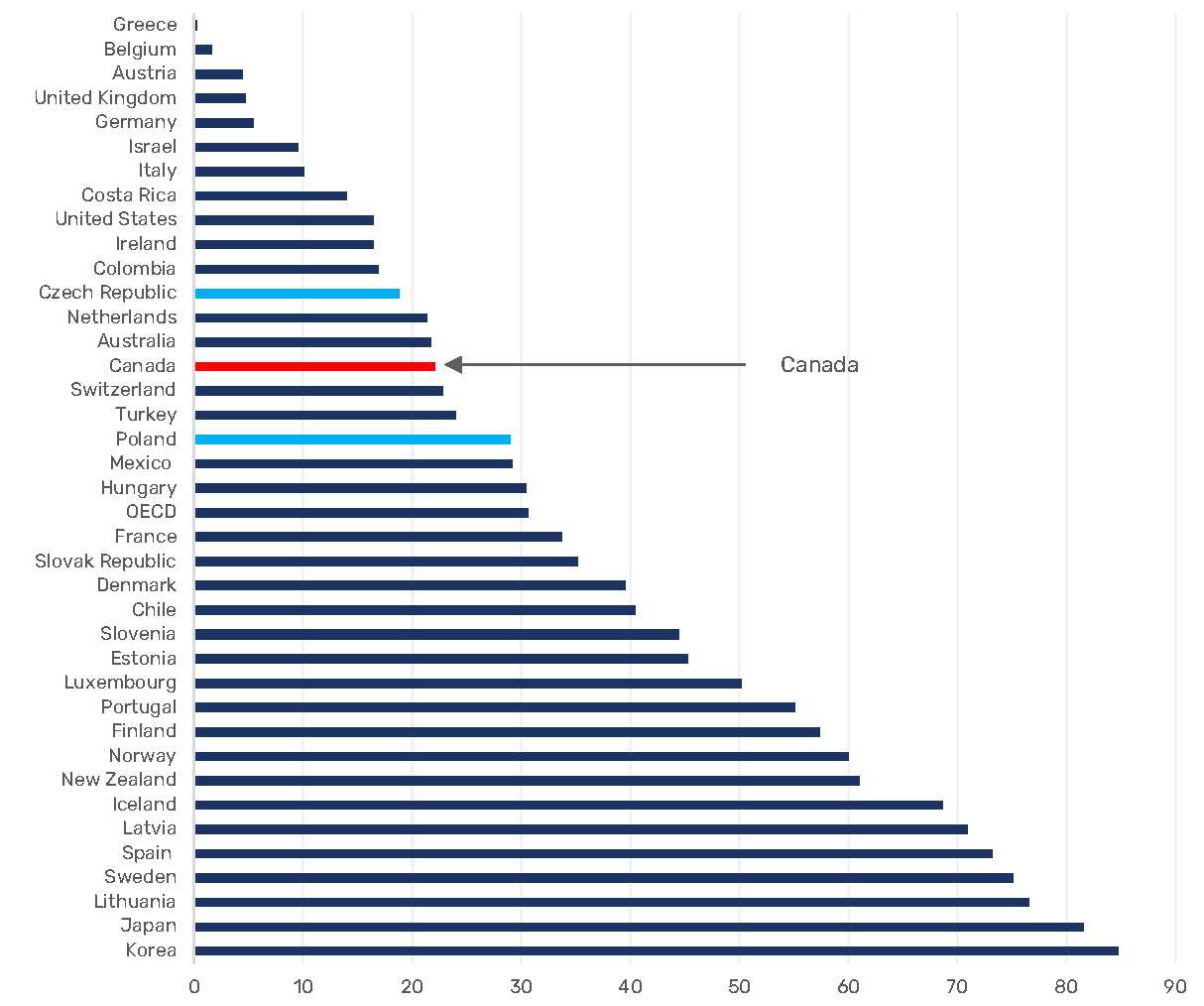

Despite this significant growth, mobile broadband (i.e. mobile internet) adoption and usage in Canada has consistently ranked poorly when compared to other OECD countries. In 2020 Canada dropped five ranks, from an already lowly 32nd out of 37 OECD countries for broadband wireless penetration, to 37th of 38 OECD countries in 2020. Canada’s mobile service adoption has consistently been below the US, UK, Denmark, Australia, and the vast majority of other OECD countries. Figure 6, below, illustrates the point. Moreover, this is a position that Canada has languished in for a decade-and-a-half (Benkler, Faris, Glasser, Miyakawa, Schultze, 2010; OECD, 2011).

Figure 7: OECD Wireless Broadband Subscriptions per 100 inhabitants, by Technology, December 2020

Source: OECD Broadband Portal.

Like other sectors, revenue growth in mobile wireless slowed post-2008. Already as early as 2013, some observers argued that this was the result of a maturing market (Church & Wilkins, 2013, p. 40). That explanation, however, ignores the under-development of the mobile wireless market in Canada relative to all but a few of its OECD peers. In addition, continued growth of the sector has shown this prediction to be incorrect.

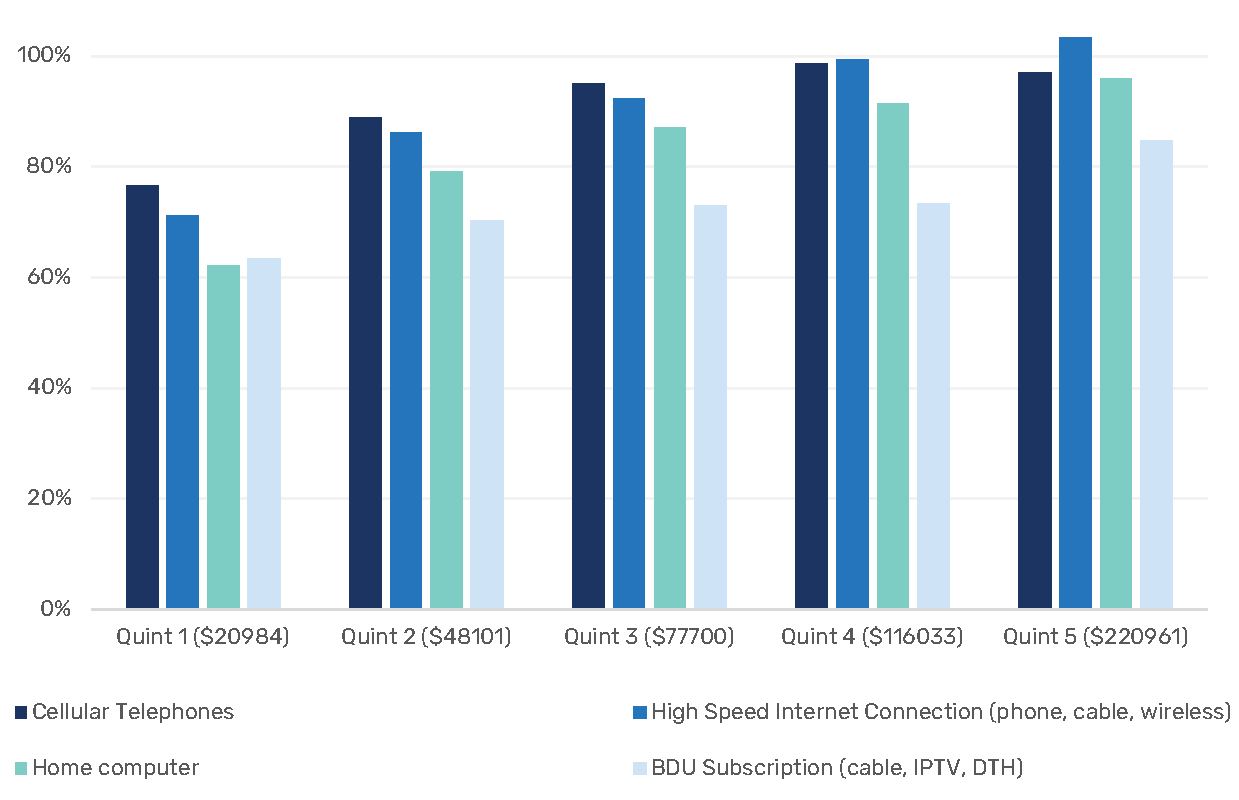

Although revenue continues to grow at a significant rate, adoption levels in Canada have lagged behind our peers, and remain stratified by income.

As of 2019 (the most recent year for which data are available), just fewer than one of four (23.6%) of households in the lowest income quintile did not subscribe to a mobile wireless service, while approximately 1 out of 10 (11%) of those on the next rung up the income ladder stand in the same position. Although these figures do represent small improvements in recent years, there is still a significant gap that remains open. At the opposite end of the income scale, for example, mobile wireless penetration is nearly universal at 98.7%.

Figure 8 illustrates the levels of adoption for mobile phones by income quintiles in Canada as of 2019, as well as for broadband Internet, home computers and cable television.

Figure 8: Household Adoption to Information and Communication Technologies by Income Quintile, 2019

Source: Statistics Canada (2021). Survey of Household Spending.

In the past, proponents of the status quo—who look favourably upon the economic performance of the sector while ignoring the concerns of those who struggle to afford access to this crucial service—have attempted to distract attention from these low levels of penetration by touting the supposedly large number of subscribers who have smartphones. However, as the OECD data presented above show, adoption of mobile broadband services in Canada—smartphone connectivity, that is—remains woefully low by international standards (OECD, 2020).

Canada has also historically fared poorly in terms of mobile data usage, and 2020 was no exception. Canada ranking 32nd of the 36 OECD countries that reported this information for 2020. It is true that, with an average of 3.4 GB of mobile data usage per subscriber per month last year, Canada’s performance on this metric improved (from 2.9GB/mo. in 2019). However, such improvement was meagre compared to nearly all of its OECD peers. The rate of growth in Canada is slower than elsewhere as well.

Mobile usage in Canada remains well below the OECD average of 7.4 GB per month (up from 5.8 GB per month in 2019), and dramatically behind usage levels in countries such as Finland (31 GB, the leader), Austria (25.75 GB), Korea (11.5 GB) Sweden (12 GB) France (9.7 GB), the US (9.2 GB), Australia (9.25 GB) and the UK (5.3 GB) and (OECD, 2020; FCC, 2020, para 27).

There are many reasons for this state of affairs, but price and affordability are two key considerations (OECD, 2018; Klass & Winseck, 2019). The concentrated structure of mobile wireless markets and diagonally-integrated nature of the firms that operate in them are also key factors (Genakos, Valletti, & Verboven, 2017). Incoherent policies and inconsistent actions by the CRTC, Competition Bureau and ISED/Industry Canada also contribute greatly to this state of affairs (see Middleton, 2017 and Ben).

While wireless services now occupy the centre of the media universe, the wireline telecoms infrastructure that supports plain old telephone service (POTS), value-added business services, Internet access, cable and IPTV networks continues in its place as a major pillar in the network media economy. Combined, these services accounted for just under half of all telecoms and internet access revenues (48.7%) in 2020, while mobile wireless services accounted for the rest.

On its own, however, plain old telephone service revenue fell to $12.9 billion last year—far off the high-water mark of $21.2 billion in 2000. The steep drop-off in revenue, however, has slowed in recent years, with losses offset by gains in internet access, IPTV and cable revenues. In addition, most of the telecoms and cable companies such as Bell, Telus, Rogers, Shaw, Quebecor and Cogeco were acquiring data centre operations in the early part of this decade but in the past few years all but Bell have reversed course and sold off their data centres to firms specializing in cloud computing.

More recently, some firms have moved into the provision of specialized services; for instance, Telus has begun to offer healthcare-related services accounted for within the ambit of its wireline division while in December 2020 BCE acquired the biggest data analytics firm in Canada, Environics. The lack of available disaggregated data with respect to these firms’ services, however, does not allow us to gauge the scale of these activities with any precision. Still, it is worth noting that these activities may be coming to play an increasing role in the wireline activities of major Canadian telecommunication companies. As such, they open up new vectors of diversification and vertical integration.

Internet access revenues have grown immensely over time, similar to mobile wireless. Internet access revenues were roughly $13.9 billion last year, up from $12.7 billion the previous year, and close to eight times what they were at the turn-of-the-21st century ($1.8 billion).

The adoption of wireline Internet access in Canada is high relative to other OECD countries, but so too are prices, while available speeds are mediocre, data usage comparatively low (330 GB per household per month in 2020), and data caps commonplace, whereas in most comparable countries they are rare and overage charges not nearly as punishingly expensive.7

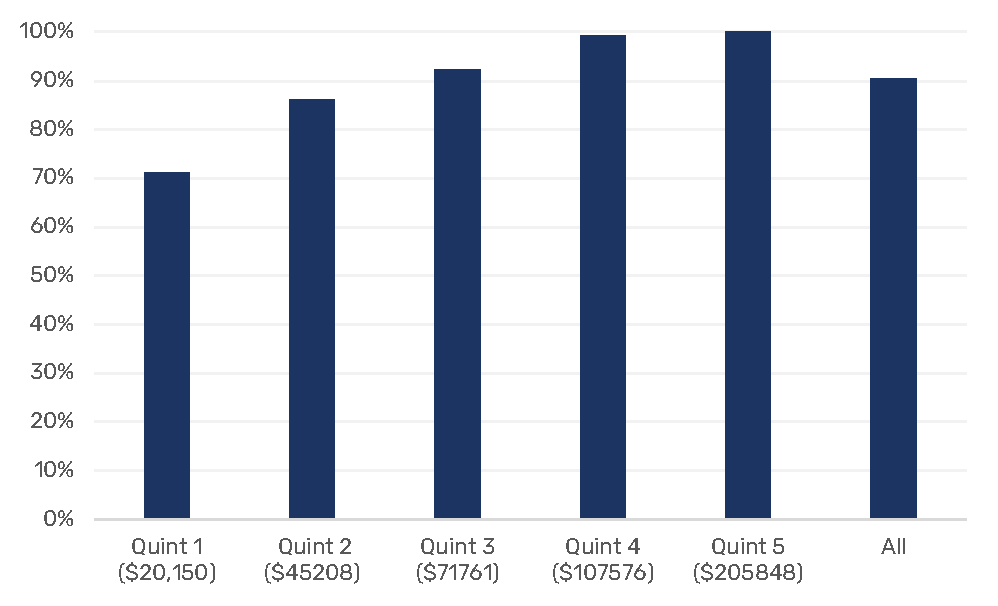

Also, like mobile wireless services, high-speed and broadband Internet access are far from universal. According to Statistics Canada’s most recent data (2019), 90.4% of households have adopted high-speed internet access service (i.e. > 1.5 Mbps), as shown in Figure 9, below. If we consider the uptake of services that meet the broadband universal service target of 50 Mbps up and 10 Mbps down adopted by the CRTC in 2016, 62% of Canadian households met that target in 2019 (CRTC, 2020, p. 50). There are also significant disparities in access between urban versus rural and remote areas, and people’s adoption of broadband is divided starkly along income lines as well.

Figure 9: High-Speed Internet Adoption by Income Quintile, 2019

Source: Statistics Canada (2021). Survey of Household Spending in 2019.

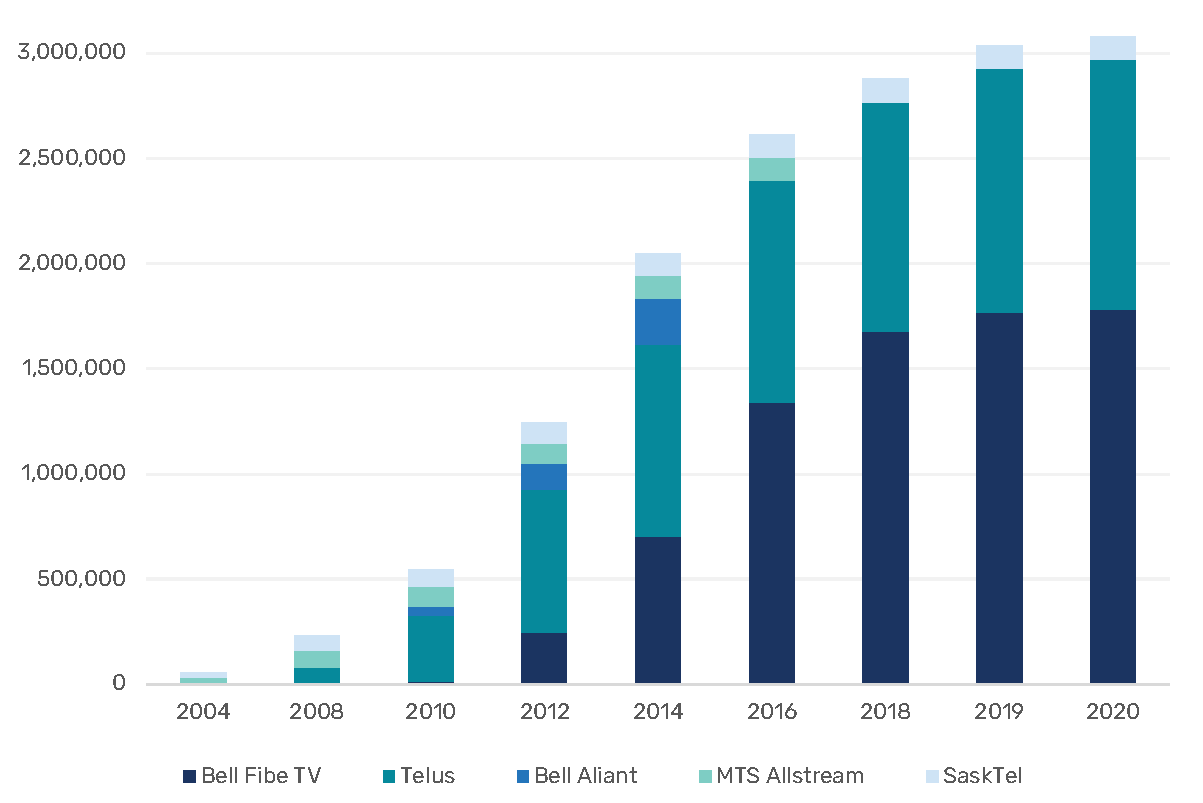

A key development over the past decade-and-a-half has been the growth of the telephone companies’ (e.g. Telus, Bell, SaskTel) Internet Protocol TV (IPTV) services. This took place slowly at first but since 2010 the pace of IPTV development has quickened. By the end of last year, the incumbent telcos’ managed Internet-based television services had over 3.1 million subscribers between them. As a result, the telco’s IPTV services now compete extensively with traditional cable television services in cities across the country. Figure 10 below shows the growth in IPTV subscribers over the past decade-and-a- half.

Figure 10: The Growth of IPTV Subscribers in Canada, 2004-2020

Source: see the “Cable DTH IPTV” data sheet in the Excel Workbook.

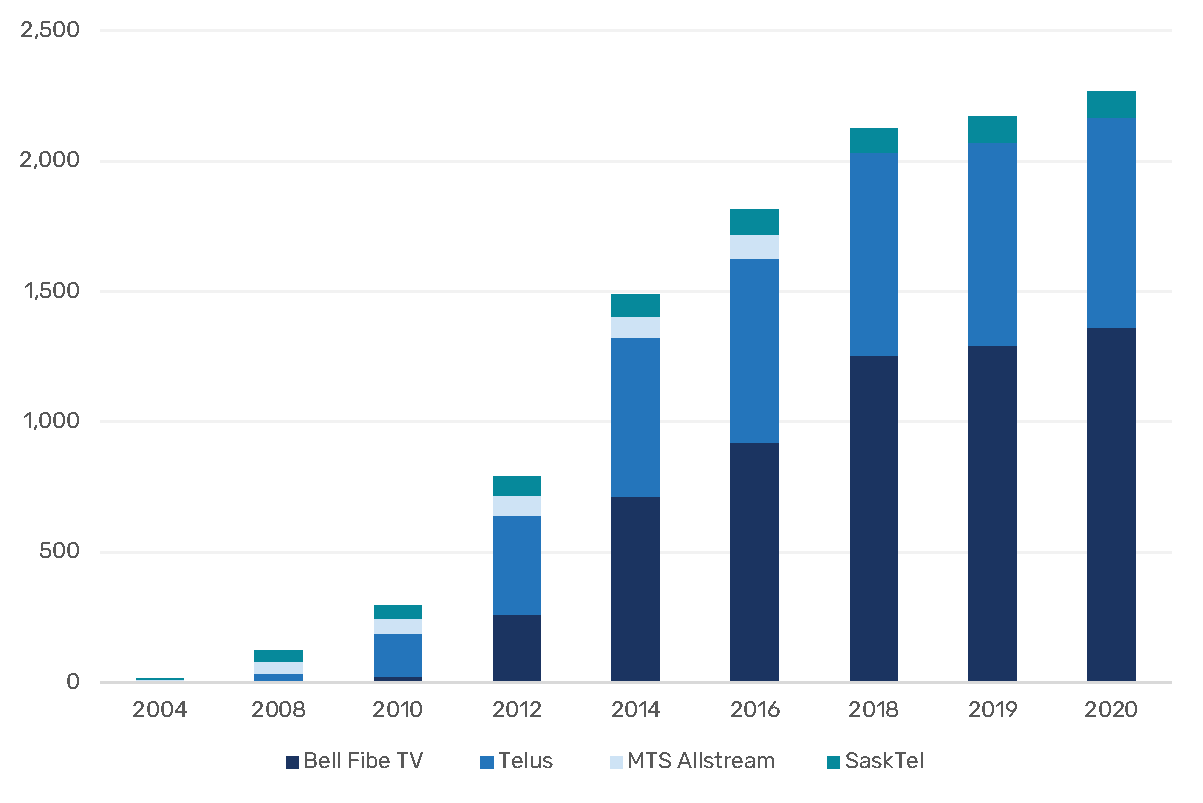

The telcos’ revenue from IPTV service has also increased sharply from $1 billion in 2013 to nearly $2.3 billion last year–again. Figure 11 below shows the trends.

Figure 11: The Growth of IPTV Revenues in Canada, 2004-2020

Source: see the “Cable DTH IPTV” data sheet in the Excel Workbook.

MTS, SaskTel and Telus first began to deploy IPTV in the prairie and western provinces in the mid-2000s. Bell initially lagged behind its western Canadian counterparts but began to follow suit in the early 2010s, perhaps because it did not want to cannibalize its direct-to-home satellite television service. Fast forward to 2020, and the telcos’ IPTV services now account for 30% of the TV distribution market based on subscribers, or 28% based on revenue. The fact that telecoms operators’ IPTV services have gained market share at the same time that “cord cutting” has picked up steam has significantly added to the competitive pressure that the cable companies now face from the telcos’ IPTV services.8

Figure 12 below illustrates these points.

Figure 12: Cable & Satellite Provider vs IPTV Revenues, 1984-2020 (current $, millions)

Sources: see the “Cable DTH IPTV” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

As Figure 12 also shows, cord cutting—the process whereby people drop their cable, IPTV or DTH service in favour of accessing audiovisual media services directly over the Internet (or over the air, or not at all)—has gained traction since 2014. While substantial growth in IPTV services over the past decade delayed this trend, the number of subscribers for all broadcast distribution undertakings has slipped from 85.6% of households at its highpoint in 2011 to 69.8% last year. In short, cord-cutting is real.

Moreover, lost subscribers has translated into sizeable revenue losses to the BDU sector; revenue fell from $9.7 billion in 2014 to $8.1 billion last year—a decline of 17%. Those losses, however, were deferred for several years by steep increases in subscription prices for BDU services. At the same time that people have been dropping their cable service to access online video services directly, the price of Internet access has also jumped. As a result, the price of subscriptions for cable TV and Internet access have risen well above increases in the consumer price index, as Figure 13 below illustrates.9

Figure 13: The Price of Communication Services and Devices vs the Consumer Price Index, 2002-2020

Source: Statistics Canada. Table: 18-10-0005-01 (formerly CANSIM 326-0021)—Consumer Price Index, annual (2002=100).

IPTV services are also important because the distribution of television and entertainment services are critical to driving the demand, and thus the revenue, telecoms operators need to invest to bring next generation fibre optic broadband networks to people’s doorsteps (see below).

The rate of IPTV adoption in Canada is relatively high by international standards, with 30% of all BDU subscriptions being to IPTV services in 2020. This level of IPTV adoption is higher than the U.S. (8.9%), Germany (14.2%), the UK (16.9%) and Japan (26.1%) but behind IPTV adoption levels in Western Europe as a whole where IPTV and cable subscriptions are nearly equal (35.7%), China (44.2%) and France (78.4%) (S&P Global, 2021).

While Canada has done fairly well with respect to IPTV availability and adoption, the picture changes for fiber-to-the-premise/doorstep (FTTP), which, as Susan Crawford (2019) observes, represents the gold standard of telecommunications networks, and will be a requirement for future economic growth. Indeed, just 22% of broadband connections in Canada use FTTP compared to the OECD average of 31%. At the high end of the scale, in Norway, Finland, Sweden, Japan and Korea, 60% to 85% of all broadband connections are fiber- based. According to the OECD, Canada ranked 24th out of 38 countries on this measure as of December 2020. Figure 14 below illustrates the point.

In sum, when it comes to fibre-optic networks, the prairie telcos and Telus were the first do deply them in the mid-2000s while Bell only began to do so in a substantial way after 2010. Globally, Bell’s late turn to IPTV and FTTP in Ontario, Quebec and Atlantic Provinces means that Canada continues to lag significantly behind comparable countries on this measure.

Figure 14: Percentage of Fibre Connections Out of Total Broadband Subscriptions (December 2020)

Source: OECD (2020). Broadband Portal, Table 1.10.

The general evolutionary pattern that we see with respect to fibre network deployment in Canada replays a long-standing practice whereby new services start out as luxuries for the rich before a combination of competition, public pressures and firm regulatory measures turn them into affordable necessities for people at large (see Richard John with respect to the US history, Robert Babe for Canada). Current debates over access to broadband fibre infrastructure are the latest iteration of this old story (Winseck Reconvergence, Winseck and Pike, John, Babe, Middleton). In fact, this could be seen at the end of 2016, when the CRTC set new standards for universal and affordable broadband Internet service: minimum speeds of 50 Mbps up and 10 Mbps down to 90% of the population by 2021 (and the rest of the country a decade to a decade-and-a-half later), and with an unlimited option on offer—that is, an Internet connection with no data cap. While the idea of unlimited Internet service was the norm in Canada before 2010, and remains so for most people in the developed world, today it is just one available options amongst others and expensive in Canada.

Policymakers have recognized that access to the Internet is no longer a luxury. This has been made especially clear during the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020. That said, large strides will be needed to ensure that aspirations meet the reality on the ground, as Canada’s standing with respect to deployment and adoption of fibre-to- the-doorstep reminds us.

A similar relatively large view of the public’s interests was pursued in early 2017 under the previous CRTC chair, Jean-Pierre Blais, when the regulator adopted new rules that stop the telcos and ISPs from using zero-rating to pick and choose some services, apps and content that won’t count against subscribers’ monthly mobile wireless data caps while everything else does. While zero-rating can be attractive to the companies as a way to differentiate their services from those of rivals, and to some consumers who see this as way of getting data for “free”, such practices are better seen as marketing gimmicks propped up by artificially low data caps and limited choices. In places where data caps are large or non-existent, zero-rating is rarely used, whereas in countries where they are low, like Canada, it is far more common—at least until the CRTC’s ruling that effectively banned it.

While the U.S. has never banned zero-rating, the EU has taken a restrictive approach. A series of four rulings by the European Court of Justice between 2020 and September 2021 clarified matters and add up to an effective ban on such practices. Together, these decisions found that zero-rating some services while throttling others once data allowances are met as well as limitations on roaming, tethering and speed all violated net neutrality rules in the EU.

The de facto ban on zero-rating in Canada and the EU (and India) are important for several reasons. For one, while mobile wireless markets tend to be highly concentrated around the world, when there are no stand-alone mobile network operators and/or maverick firms—as in Canada—data allowances tend to be low and extensively used. This reality is further aggravated in contexts where carriers also own TV and entertainment services, as is in Canada, because under such circumstances carriers have the incentive and the ability to zero-rate their own services while counting everything else towards subscribers’ monthly data allowance.

In other words, several structural features of broadband and mobile wireless markets in Canada bias them toward low and restrictive data caps and a desire by service providers to adopt “zero-rating” as an alternative to giving people bigger data allowances, or even making unlimited services the norm rather than an expensive and rare option (see, for example, Rewheel/Digital Fuel Monitor, 2021). As we saw earlier, Canada also has low levels of mobile data usage; these two things are closely related.

Ultimately, questions about zero-rating embody a philosophy of communication, one that says that when data caps are high or non-existent, people can use bandwidth to communicate, entertain, express themselves, work and do with as they want—within the limits of the law. When they are low, however, what people can and cannot do with “the means of communication” at their disposal is artificially restricted to serve the carriers’ business models and profits. Seen from this angle, the issues at stake are not just about prices but whether the speech and editorial rights of people, “content creators and distributors”, apps makers and service providers come first or whether those of the carriers and ISPs are paramount? In early 2017, the CRTC ruled in favour of the first group, and drew on the principles and history of common carriage10 to do so (see Klass, Winseck, Nanni & McKelvey, 2016).

Both rulings—the 2016 decision setting out new basic service standards and the 2017 zero-rating decision—staked out a fairly ambitious view of what Canadians need and deserve in “the digital media age”. On the one hand, the basic services ruling includes affordable access to high- quality communication services and gives priority to the expressive rights of people, content creators, apps developers and service providers over the those who own broadband Internet access and mobile wireless networks. Consequently, people do not have to accept only what the market gives them because communication needs have been recast in a more expansive way in the light of conditions in the 21st Century.

On the other hand, the carriers do not like this run-of-events and have wasted no effort fighting to change it over the course of the last year. Thus far, they have not been able to roll back the gains on the net neutrality/common carriage front. In terms of the basic service objective, however, they have found a friendly ear with the new Chair of the Commission, Ian Scott, who has taken a miserly view of what people should expect with respect to more affordable mobile wireless and broadband Internet services (e.g. CRTC 2018-475), and has accordingly reversed course when it comes to creating more competitive conditions in both mobile wireless and wireline broadband access markets that would help further such aims.

To this end, for example, the CRTC under Scott has, in essence, rejected the Mobile Virtual Network Operator (MVNO) option and taken only extremely limited and thus far largely ineffective steps to address the affordability issues that have plagued the mobile wireless sector for decades (CRTC, 2021-130). Early this year, the Scott-led CRTC also reversed the Commission’s own previous decision with respect to the wholesale pricing regime for independent ISP access to the incumbent telco and cable company’s networks, siding with incumbents by raising wholesale rates with little explanation or justification. The effect was to reinstate higher wholesale rates that the Commission had previously found to be inflated while taking that earlier ruling’s requirement that incumbents reimburse independent ISPs for excessive charges off the table (CRTC, 2021-181). It was an extraordinary about face.

Scott’s initial appointment in 2017 as CRTC chair for the next five years was met with skepticism. Yet, critics, reformers and public interest advocates were also willing to suspend judgement because they had also come to learn that, in the recent past, their early suspicions of appointees who seemed too close to

The CRTC also reversed course earlier this year when it decided not to extend competitors’ access to the inside wiring of condos and apartment buildings to include fibre-optic wiring. As a result, competitors The CRTC also reversed course earlier this year when it decided not to extend competitors’ access to the inside wiring of condos and apartment buildings to include fibre-optic wiring. As a result, rivals who seek access to condo and apartment-building residents can get that access so long as the ‘inside wiring’ is made of copper but not to upgraded fibre networks. This effectively tied the pro-competitive regime that had been in place for two decades to a technology—copper wiring—from last century rather than upgrading it to the infrastructure standards of the 21st Century, i.e. fibre (CRTC, 2021-139).

Taken together, the decisions discussed above represent a remarkable reversal for the CRTC; from a regulator that had under the Conservative appointed leadership of J.P. Blais embraced a principled approach to its legislative mandate (however imperfectly), it now appears to have settled back into the disturbing role of captured protector of incumbent regulated entities.

Scott’s appointment in 2017 to a five-year term as CRTC chair was initially met with skepticism. Yet, critics and public interest advocates were also willing to suspend judgement because they had also come to learn that, in the recent past, their early suspicions of appointees who seemed too close to industry and/or government had been misplaced. This was the case, for example, for Tom Wheeler’s position at the helm of the FCC in the U.S. in 2013, where the initial fear was that his previous role as the CEO of the Cellular Telecommunications and Internet Association was akin to putting the fox in charge of the henhouse. Instead, Wheeler turned out to be a strong, public interest oriented head of the FCC for the rest of the Obama Administration. Likewise, in Canada, there was concern that putting Daniel Therrien, a former national security specialist in the Harper Government, in charge of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC) in 2014 would end up being a terrible mistake. They were wrong, by and large, and the OPC under Therrien has taken on issues that confounded early expectations, and with impressive results. He has also held the current Liberal Government’s feet to the fire with respect to its lackluster legislative proposals on this front while also leading the charge for strong, human rights-based approaches to privacy and data protection rules fit for a new phase of communications and Internet regulation.

Today, whatever goodwill had existed for the leader of the CRTC has run dry, due to the record of Ian Scott’s actions as helmsman of the regulator. While the lessons of those other appointments outlined a moment ago were taken seriously by critics, would-be competitors and public interest groups for Scott’s first few years at the helm of the Commission, his track record has proven disastrous for progressive public policy in communications.

It important, however, that the blame not be placed only on one person. The fact is, the Trudeau Government appointed Ian Scott to lead the CRTC, knowing full well that he had been a Telus executive and industry lobbyist. It is also the Liberal Government that has refused to overturn the direction he has taken the CRTC in. Moreover, the Liberal Government has treated incumbent cable and telecoms operators with kids’ gloves by adopting weak standards by which it has favourably judged the meagre price reductions realized for a select, few mid-range mobile wireless plans—i.e. those with data allowances between 2 and 6 GB per month—even though those reductions compare poorly against international trends (see, for example, Rewheel, 2021; Wall Communications, 2021).

Traditional and Digital Audiovisual Media Services (AVMS): From Ad-Supported Content Media to Fast Growing Subscription-based Digital Media

The remainder of this report shifts gears to examine ongoing developments in the media content sectors—also referred to as the AVM sectors—in the context of the following thee over-arching trends:

- the explosive growth of online advertising;

- Although advertising spending has remained fairly fixed relative to the size of the Canadian economy for decades, since 2012 it has fallen by about 10% per annum. This translates into a loss of, roughly, $1.5 billion in advertising spending across all media per year since then. Cumulatively, this means that $11.6 billion has, in essence, vanished between 2013 and 2020. As a result, traditional media sectors (i.e. broadcast TV and radio, newspapers, and magazines) and firms that depend mainly on advertising as the core of their business model are battling internet giants like Google and Facebook for a shrinking pool of revenue. The results have been devastating. Seen in this light, it should be obvious that laying the blame solely on “the vampire squids” from Silicon Valley for such losses is simplistic.

- In reality, though, the core of the media economy is not advertising but a rapidly growing group of pay-per media and digital AVMS that are based primarily on subscriber fees and direct payments. Revenue for the pay-per (subscriber) based communications and media sectors outstrip that of advertising-supported media 5:1.

These over-arching trends, in turn, are taken up in relation to an analysis of the following digital and traditional audiovisual media services (AVMS) that make up the content media sectors of the media economy:

- Internet advertising

- broadcast TV

- pay and specialty TV

- online video subscriber and download services such as Netflix, Crave, Amazon Prime Video, Rogers SN Now, Disney+ and Illico

- radio

- music, including recorded music, live concerts and revenues from publishing royalties

- online music subscription and download services such as Apple iTunes and Spotify

- online gaming, gaming applications, game downloads or in-game purchases

- app stores (e.g. Google Play and Apple Appstore)

- newspapers

- magazines

- online news

Anchor Findings

• Online advertising continues to grow rapidly, with nearly all growth captured by Google and Facebook.

• Regulators must contend with the consequences of this duopoly not only in online advertising, but also to curb their ability to leverage that dominance into adjacent media sectors.

• The digital duopoly dominance is entrenched and has been consolidated over the last decade.

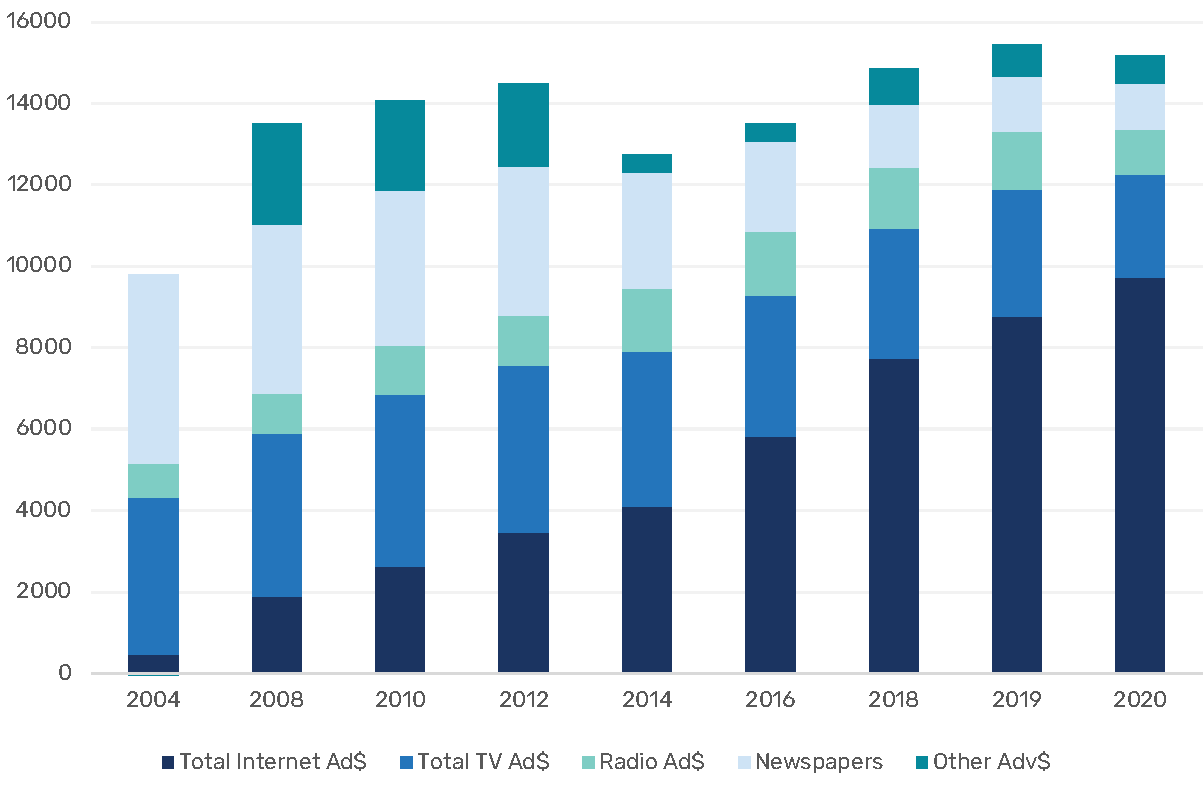

Overall advertising spending has been hurt badly by unsteady economic conditions since 2008, and this was compounded by the economic contraction last year brought about by the Covid-19 pandemic. At the same time, however, online advertising has continued to surge ahead, even last year. By last year, Internet advertising revenue in Canada reached an estimated $9.7 billion—up from $8.8 billion a year earlier and now worth more than four times what it had been a decade ago.

Google and Facebook have been the biggest beneficiaries of this soaring growth, with estimated advertising revenue of $4.9 billion and $2.9 billion, respectively, in 2020. Google accounts for half of the Internet advertising market, while Facebook’s share is approaching the one-third mark. Together, they controlled four-fifths of the online advertising market in Canada in 2020—up significantly from a little over two-thirds share of the market just five years ago.

Moreover, a majority of the new growth in Internet advertising revenue has ended up in their coffers, although the pace of this trend has been down substantially in the two most recent years from previous years when Google and Facebook took four-out-of-five dollars in new growth. In short, the digital duopoly’s grip on the online advertising market is tightening, enduring and entrenched.

These are all key considerations that have motivated a series of recent public inquiries and regulatory actions in Australia, the UK and the U.S. and justify actions that aim to lessen or break-up the foundations of Google and Facebook’s dominance. Such actions include decisions already taken or proposals on the table that they be required to adopt new forms of operational separation—i.e. between Google’s search functions and suite of services on the one side and digital ad exchange, on the other, or between Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram, for example—or to spin-off operations that underpin their stranglehold over much of the online services and advertising system.11 In Germany, the principle of operational/data separation was implemented in 2019 and survived Facebook’s unsuccessful court challenge to this measure.12

We will address such issues more fully in the next report.

Open the lens wider to examine adverting spending in all media, e.g. Internet, television, radio, newspapers, magazines and out-of-home—and the picture, however, is more complicated.

First, total advertising spending in Canada last year was $15.2 billion, down $300 million from the year before. Figure 17 illustrates the point. Yet, even this substantial drop masks a harsher reality: take out online advertising where growth continued apace, albeit at a slower pace than usual, and ad spending across the rest of the media landscape plunged by 18.5%. This was disastrous for media sectors and firms where advertising is the core of their business.

The upshot of these developments is that the collapse of advertising spending outside of online advertising amidst the Covid-19 pandemic further solidified Google and Facebook’s emergence as the two biggest recipients of ad revenue in Canada. Together, they accounted for just over half of the advertising market last year, up from just over a third in 2017. As the digital duopoly lock in their grip on the advertising market, other major players in Canada are falling further into the rearview mirror.

The largest such player, Bell, by comparison, attracted just 8.3% of all advertising spending in Canada last year, down a percentage point from the year before. Rogers and Shaw also saw their share of the advertising market slip to 4.5% and 3.6%, respectively.

All told, these changes have propelled Google into being the fourth largest company operating in the media economy in Canada, after Bell, Telus and Rogers; Facebook is seventh after Shaw and Quebecor. Together, the top five Canadian media companies based on advertising receipts—Bell, Rogers, Shaw, Quebecor and the CBC—saw their collective share of total advertising spending tumble from just under a quarter in 2019 (23.9%) to less than one-fifth last year (18.3%).

These trends represent a substantial change from just a few years ago. Take, for example, the fact that in 2017, by the lights of two conventional measures of market concentration—concentration ratios and the HHI—the advertising market was one of the most competitive relative to all other sectors of the communications and media economy that we analyze. By 2020, that was no longer true. Instead, Google and Facebook’s control of more than half the market was a clear indicator of a consolidating duopoly, while the CR4 score of 64% and an HHI of 1518, respectively, revealed high- to moderate levels of concentration, and with a rapid upward tendency.

In sum, concerns about Google and Facebook’s dominance of the advertising market in Canada, and calls for firm measures to do something about that, are fully supported by the evidence. We will address this issue in much greater detail in the next report.

Within Canada and globally, Google’s dominance of online advertising is girded by the fact that it has vertically integrated its search and online advertising functions with its own proprietary digital advertising exchange (and the buying and selling of advertising inventory on both sides of that exchange), to say nothing of the dominant position it holds in relation to mobile and desktop browsers, the Android mobile operating system, and Google Play app store (typically in duopolistic rivalry with Apple in each of these areas). The cornerstone in Google’s sprawling reach across the Internet stack, however, is the online advertising system that it has assembled through a series of acquisitions over the last decade (e.g. DoubleClick, AdMob, etc.). By assembling its own online advertising exchange, Google has, in essence, erected a walled garden around its services as well as the buying and selling of audiences and advertising inventory on the Internet, a stark contrast from its early promise to help people navigate the ‘open Internet’ and to slay the walled gardens that had emerged in the late- 1990s.

While Facebook does not have its own digital advertising exchange, both it and Google share the fact that they control the common currency used to buy and sell audiences and advertising inventory online: detailed knowledge of their audiences. Each firm also has its own audience measurement and rating system that allows them to control the terms of trade upon which the online advertising system functions.13 By controlling the building blocks of the online advertising system both companies are able to effectively hold third party advertising campaigns hostage because neither of them interconnect with one another, or with other digital platforms. Consequently, advertising campaigns, and the data, costs, and labour behind them, are not portable between competing advertising exchanges, thereby allowing Google and Facebook, in effect, to use this control to hold audiences and advertisers hostage. This raises the prospect of using mandated data portability, network interoperability and interconnection obligations to put a dent in their dominance(another point we will return to in the next report).

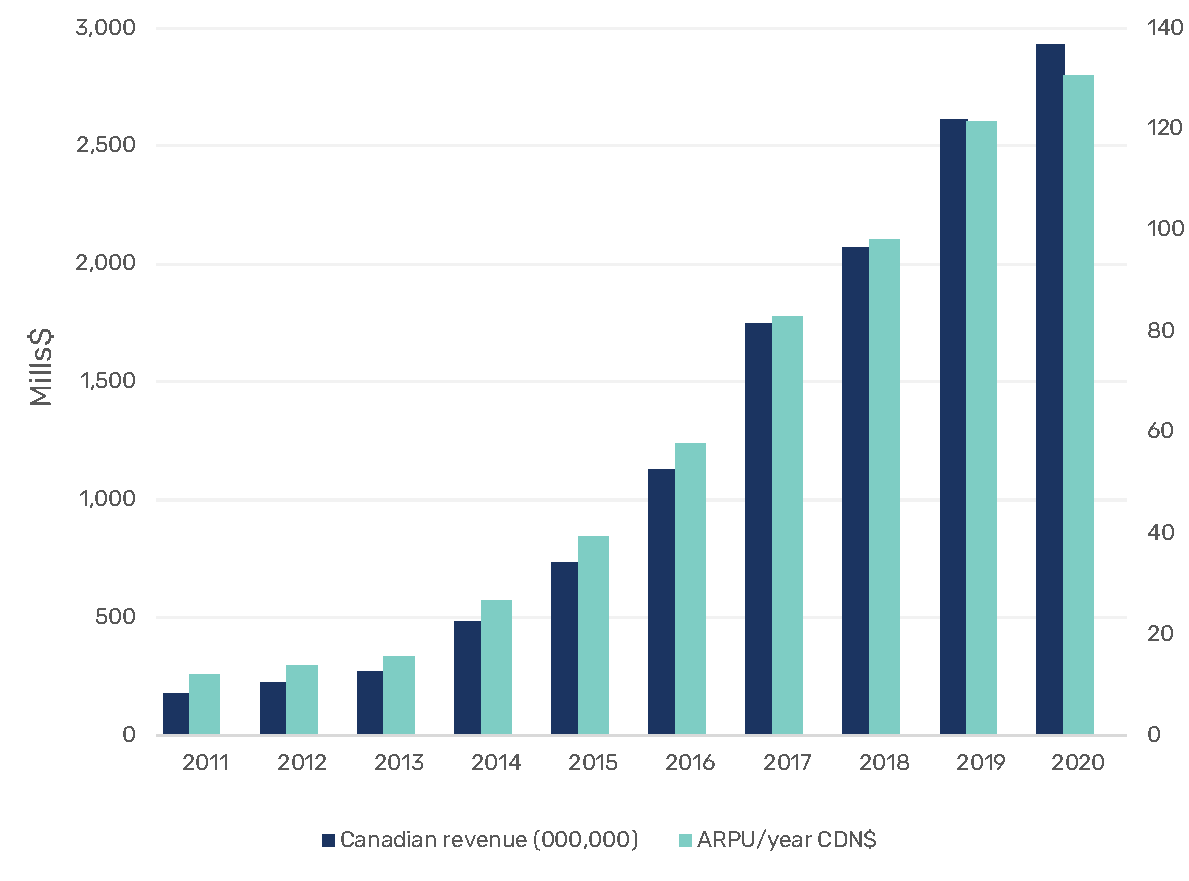

For its part, Facebook had 21.5 million users in Canada at the end of 2019 and revenue of $2,614 million. The company has benefitted in particular from the shift from “desktop Internet” to the mobile Internet. Thus, while Facebook had only a few dozen people working on the mobile Internet version of its app as late as 2012, by the end of that year it had done an about face as it acquired Instagram and set out to make the mobile Internet its new frontier of expansion. As a result, the mobile version of Facebook’s service is now the centre of the company’s operations.

The growth rate for the number of people using the company’s three main services—Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp—in Canada has been swift over the past decade but it has slowed in recent years. Slowing growth in the size its user based has not caused revenue growth to stall, however, because Facebook has focused on sharply increasing the monetary value of each user. And it has succeeded at this as well. The annual average revenue per Facebook user (ARPU) in Canada last year was $130.74—triple what it was five years ago and thirteen times what it was in 2011.

Figure 15 below depicts the growth of Facebook’s revenue and ARPU in Canada since 2011.

Figure 15: Facebook’s Revenue and Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) Soar, 2011-2020

Source: see “Facebook Revenue” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

In sum, Google and Facebook have become major players in Canada in a short period of time. The duopoly they initially formed in the Internet advertising market has now expanded to encompass the whole advertising market.

Based on these trends, it has become an article of faith in many quarters that Google and Facebook are the primary cause of an existential crisis besetting the media in Canada, writ large. While such charges might seem to be compelling at first blush, they are superficial and deeply misleading.

This is because, first and foremost, there is no general crisis of the media. To the extent that there is one, it is limited to four media sectors that have historically relied almost entirely on advertising revenue: broadcasting television, radio, newspapers and magazines. These media sectors are in trouble. Collectively, revenue for these sectors has plummeted by close to $6 billion since 2008 and by 2020. Total revenue across these four sectors is now roughly half what it had been a dozen years ago. This trend is unlikely to turn around any time soon. Figure 16 illustrates the wreckage.

Figure 16: The Rise and Fall of Advertising-funded Media, 1984-2020 (millions, current$)

Source: see “Total Revenue” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

Why is this? It is primarily because advertising spending—and thus the fate of advertising-funded media—tracks the fate of the economy in lockstep fashion (see Picard, Garnham, Miege, and Vogel). When the economy is buoyant, advertising revenue rises; when the economy slumps, advertising revenue falls.

This can be seen by tracking advertising spending since 2008, for example, the year that the financial crisis swept much of the world. Over the next year, advertising spending dropped by a little over a half a billion dollars from $11.5 billion. That lost ground was recovered in 2010. Thereafter, advertising spending for all media in Canada hovered in the $12-13 billion range for the next five years, before edging upwards, in fits and starts, to $15.5 billion in 2019, before contracting again last year (in current dollars). If you switch the metric to real dollars, the story is even grimmer, with revenue hovering between $13 and $14 billion from 2008 to 2016 before inching upwards again to $15.5 billion in 2019, before sliding again last year (i.e. CAGR of .94%).

The result of such anemic conditions was the loss of approximately $1.5 billion in advertising revenue per annum relative to what it would have otherwise been had “normal” growth rates held steady. Another way to look at this is to consider a hypothetical case where average advertising spending as a percentage of GDI stayed the same as it was before tanking. Based on this view, we can estimate that there has been a loss of roughly $11.6 billion over the last eight years or so. To make matters worse, these losses have taken place exactly as Google and Facebook were locking in their monopoly power over the online advertising system and, consequently, what remains from the stagnating/shrinking base of advertising spending in the country. This phenomenon is not unique to Canada but can also be seen in Australia, the United Kingdom and the U.S. and probably elsewhere, too.14

Figure 17 below reveals the period of relatively low to no growth between 2010 and 2016, and the slow increase for the next few years after that before advertising revenue once again tanked in 2020.

Figure 17: The Stagnating Advertising Economy, 2004-2020, (real $ 2020, millions)

Source: see the “Advertising Revenue All Media” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

The story for advertising-funded media is grimmer yet when we consider advertising spending on a per capita basis. Looking at advertising revenue on a per capita basis (in real dollars), advertising spending fell sharply from $407.60 per person in 2008 to $384.80 a year later. It then bounced around at relatively low levels of growth for the next decade, before finally returning to its previous levels since 2017. Last year, however, that small glimmer of hope was once again dashed as advertising spending on a per capita basis fell below $400 again—a negative CAGR of .175% over the last dozen years.

Zeroing in on advertising earmarked solely for television is also telling. Whereas advertising spending on television hovered around $120 per person (in real dollars) during most of the first decade of the 21st Century, it has slid continuously and significantly over the last decade. It was $67.10 per capita last year.

The fortunes of Internet advertising, of course, have run in exactly the opposite direction, skyrocketing five-fold from $57 per person in 2008 to $255.70 last year. Figure 18 below depicts these points.

In 2020, advertising spending was $420.10 per capita—a negative CAGR of .175% over the last dozen years.

Figure 18: A Ceiling for Ad Spending?: Advertising Spend per Capita, 2004-2020 (real$ 2020)

Source: see the “Advertising Revenue All Media” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

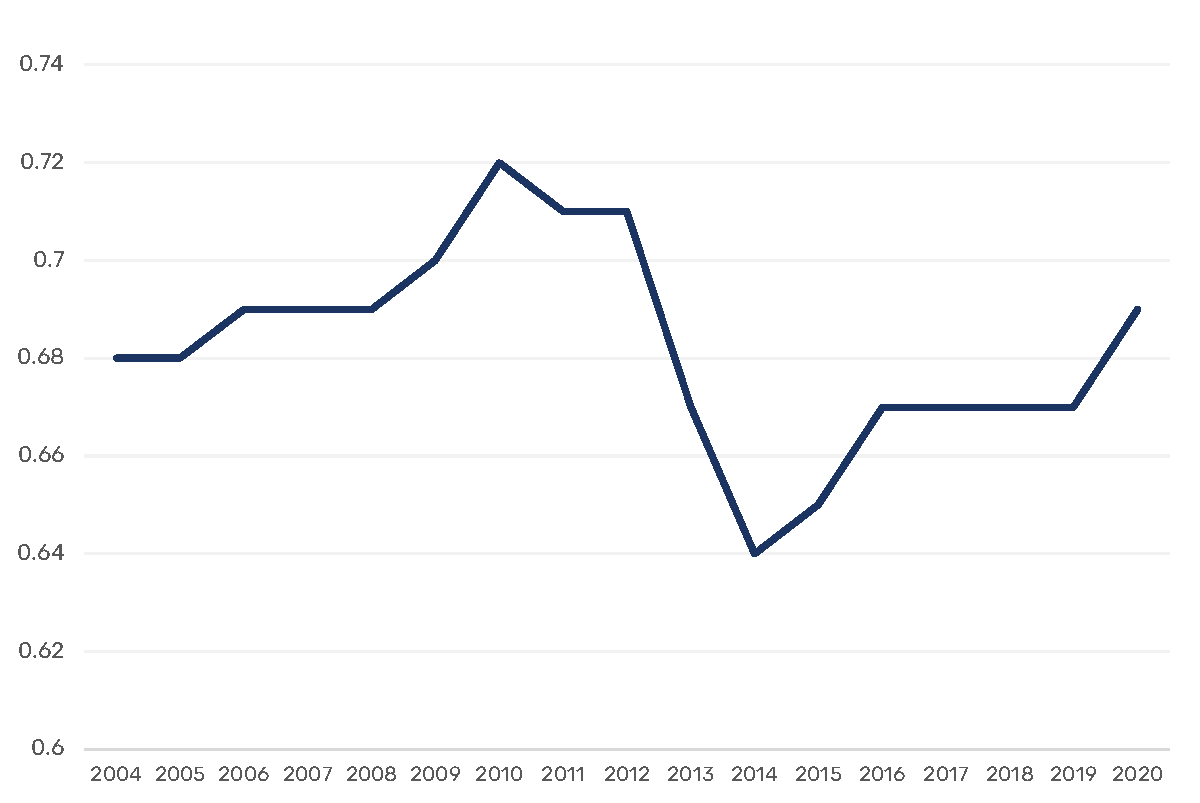

Figure 19 below also reveals a pattern of stagnating or shrinking advertising spending relative to the size of the network media economy over the last decade. In this case, advertising spending levels are lower today than they were fifteen years ago.

Figure 19: Ad Spend as a Percentage of the Network Media Economy, 2004-2020

Source: see the “Advertising Revenue All Media” sheet in the Excel Workbook.