Media and Internet Concentration in Canada, 1984-2016

Today, the Canadian Media Concentration Research Project is releasing the second of its two-part annual series on the state of telecoms-internet and media concentration in Canada. A downloadable PDF of the report can be found here.

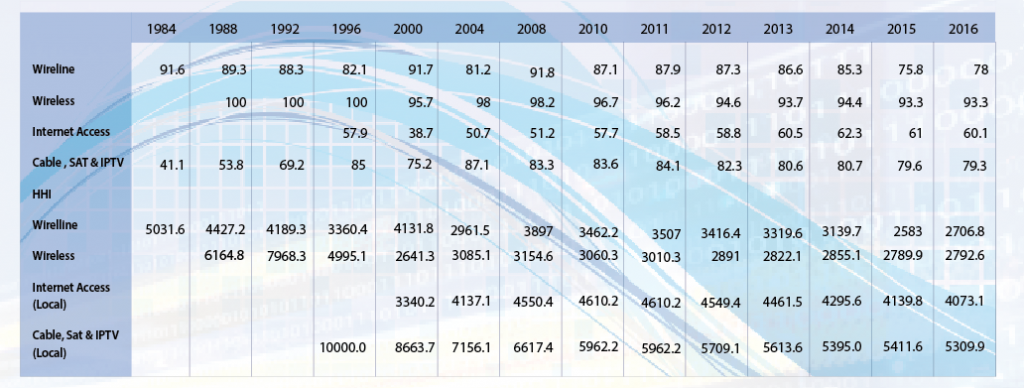

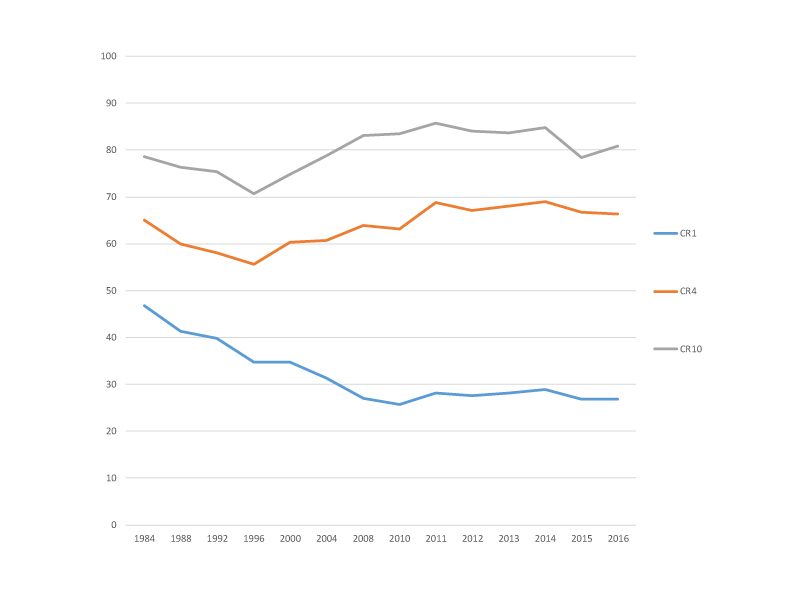

The report examines the state of competition in the mobile wireless market, internet access, broadcast, pay and streaming TV services, internet advertising, newspapers, browsers, online news sources, search, social media, operating systems, etc. in Canada over the period from 1984 until 2016. We call the sum-total of these media “the network media economy”. We then use two common metrics—Concentration Ratios and the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI)—to determine whether these markets—individually and collectively—are competitive or concentrated.

This year’s report adopts a new tack as well by taking a closer look at the state of competition in local and regional mobile wireless, retail internet access and “cable TV” services. We examine the state of mobile wireless competition in Quebec, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, for instance, where, at least in 2016, the big three national carriers—Rogers, Bell and Telus—faced strong regional rivals like Videotron, SaskTel and MTS (before the latter was taken over by Bell this year). We show that competition has improved considerably in Quebec, for example, where Videotron has carved out a 13% market share for itself in the mobile wireless market (and about 15% based on subscribers).

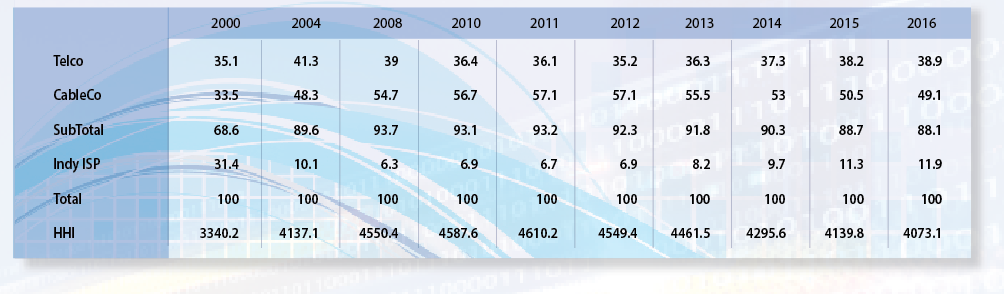

Concentration levels are much higher in local retail internet access and cable TV markets, however, where the top two firms generally account for 88% and nearly 100% of the market, respectively. In short, there are strong reasons for concern in all these markets. Now is no time to let up on policy measures that have begun to bear at least some fruit, and perhaps good reason to double-down on them.

We also identify features of the network media economy that set Canada apart from other countries. In Canada, telecoms companies, for instance, own all the main TV services except for the CBC and Netflix. This is a distinguishing feature of the network media economy and needs to be recognized and dealt with as such. Vertical integration in this country is very high by historical standards and almost four times current levels in the United States.

Even if AT&T’s current bid to acquire the film and TV giant Time Warner gets past the strong headwinds it is encountering, vertical integration in the US would be just over half the Canadian levels. The policy principle of “common carriage” (popularly known as “net neutrality”) is built for conditions like these—albeit not contingent upon them.

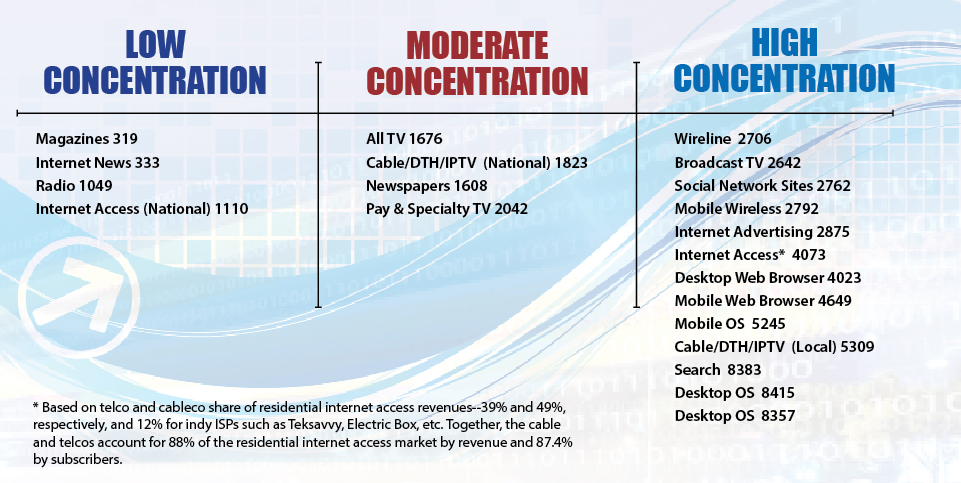

The trends we observe differ across time, place and media. After intensifying in most areas of the network media economy from 2010 to 2014, and especially in TV, concentration trends have generally drifted downwards in the past two years.

Concentration levels have fallen, for example, in cable TV (when measured locally, but not nationally), internet access (at both the local and national level), wireline telecommunications, broadcast TV, pay and specialty TV and the “total TV marketplace” (which includes internet streaming TV), internet news sources and newspapers.

Concentration levels have stayed steady for mobile wireless services, except in Quebec. This is the most competitive wireless market in the country, and it shows in terms of more affordable rates for several tiers of services not just from Videotron but each of the national carriers competing with it in the province, and higher monthly data allowances.

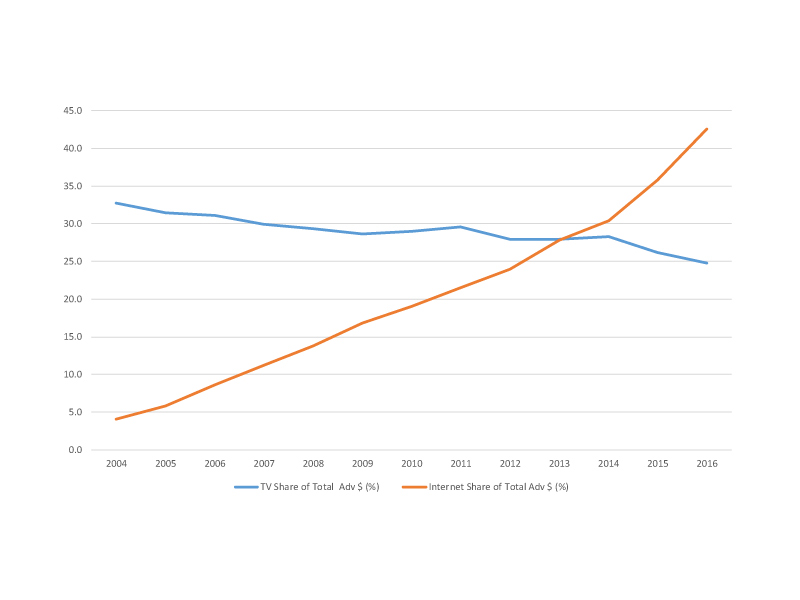

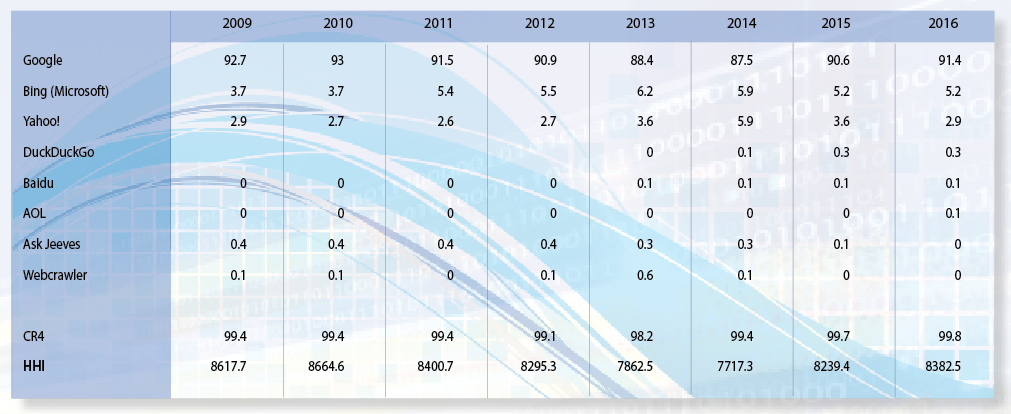

Concentration levels have risen in search, mobile and desktop operating systems, mobile and desktop browsers as well as internet advertising. This suggests that, far from being immune to consolidation, “core elements of the internet” are highly susceptible to such pressures.

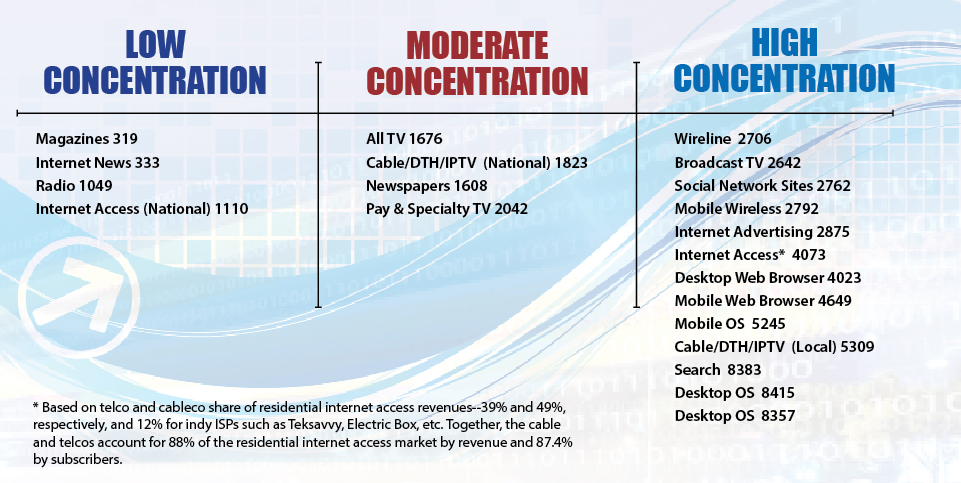

The following figure depicts the state of play in 2016 for each media covered in this report based on HHI scores.

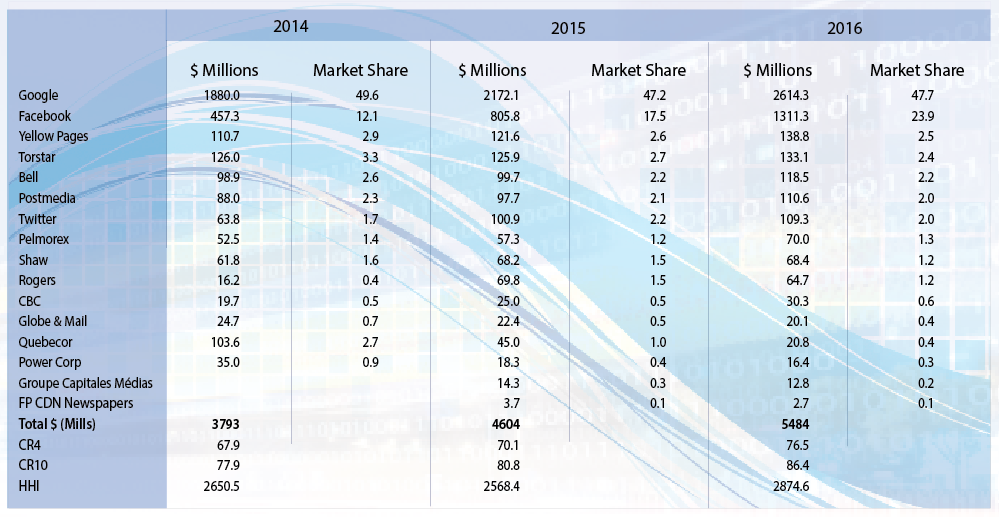

We also pay particularly close attention to Google and Facebook’s fast growing dominance of internet advertising. In 2016, the two internet hypergiants’ took in nearly three-quarters of the $5.5 billion Canadian internet advertising market (72%)—up from their two-thirds combined share the year before. The shift to the “mobile internet” has allowed both companies to consolidate their grip on internet advertising and to resurrect the old “walled garden” vision of the internet that many have thought died after the dot.com bust at the turn-of-the-21st Century: now, however, Google has search, Youtube, the Chrome browser, Android operating system, undersea cables, and the cloud in its “stack”; Facebook has messenger, Instagram and WhatsApp in its—both seek to turn their platforms into all-in-one apps where people seldom leave.

Many observers denounce Google and Facebook on grounds that they are pillaging the revenue that traditional, advertising-based media industries need to support the production of entertainment, journalism and Canadian culture. Our last report cast doubt on these claims, and this one does too by raising and exploring the following three points:

- the $5.5 billion internet advertising market that Google and Facebook dominate is a tiny part of the $80 billion media economy in Canada;

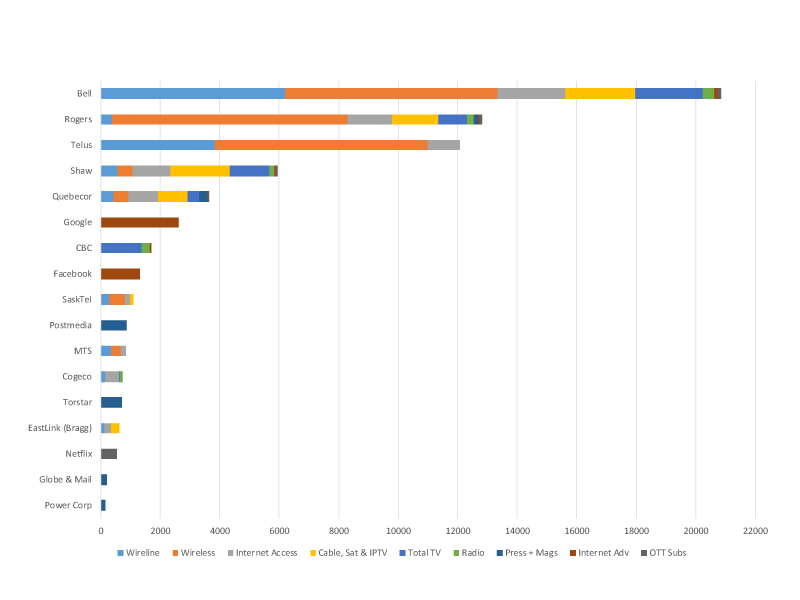

- the “big five”—Bell, Rogers, Telus, Shaw and Quebecor—are many times larger than Google and Facebook based on revenue from Canada. Bell’s revenues were eight and sixteen times those of Google and Facebook, respectively, and forty times those of Netflix. To put things in perspective, Google, Facebook and Netflix were the sixth, eighth and fifteenth biggest media companies in Canada last year based on their estimated revenues;

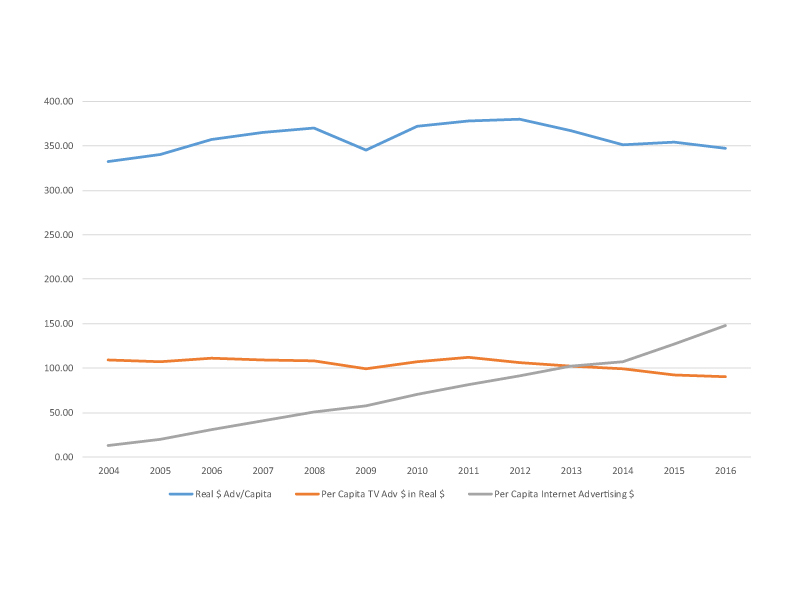

- the perception that Google and Facebook are “vampire squids” is not entirely without merit but fails to realize that the real driving problem is probably that total advertising spending appears to have hit a ceiling in real dollar terms and is declining on a per capita basis and relative to the size of the network media economy. That Google and Facebook are carving out a bigger share of a shrinking pie is undoubtedly sharpening the conflict between them and those who see them as the source of all—or at least a lot of—their woes.

Additional headlines of this report include:

- after spiking between 2010 and 2014, concentration levels have drifted downwards across the whole network media economy in recent years;

- the top five companies—Bell, Rogers, Telus, Shaw and Quebecor—accounted for 71.1% of the $80 billion network media economy last year, down slightly from 71.5% the year before;

- Bell is the biggest player in Canada by far—nearly twice the size of its closest rivals, Rogers and Telus—and it single-handedly accounted for 27% of all revenue last year—unchanged from a year earlier;

- mobile wireless is still highly concentrated with Rogers, Telus and Bell accounting for 91.2% of the sector’s revenue in 2016—down one percent from a year earlier;

- new entrants Wind Mobile and Videotron’s share of the market ticked upwards to 4.1% in 2016—up from 3.2% the year before;

- the least concentrated mobile wireless market in Canada is in Quebec, where Videotron had 13% market share by revenue and 15% based on subscribers at the end of 2016;

- incumbent telephone and cable companies accounted for 88% of the residential retail internet access market in 2016 (i.e. Bell, Rogers, Shaw, Telus, Videotron, Cogeco, Eastlink, SaskTel and MTS).

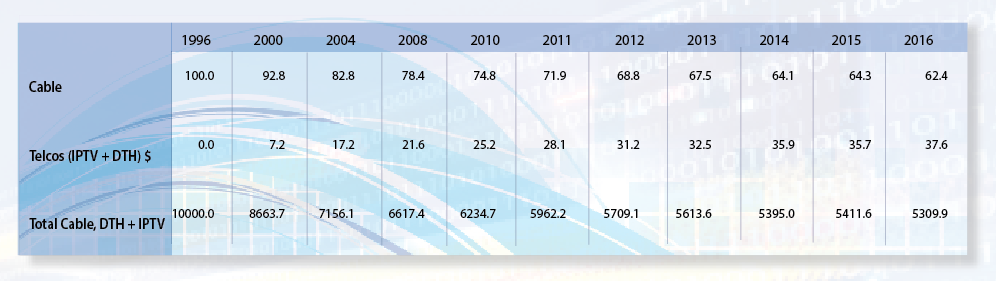

- the quick pace of IPTV growth over the past half-decade means that the “cable monopoly” is long gone. A tight duopoly persists, however, and local markets are extremely concentrated by the standards of the HHI;

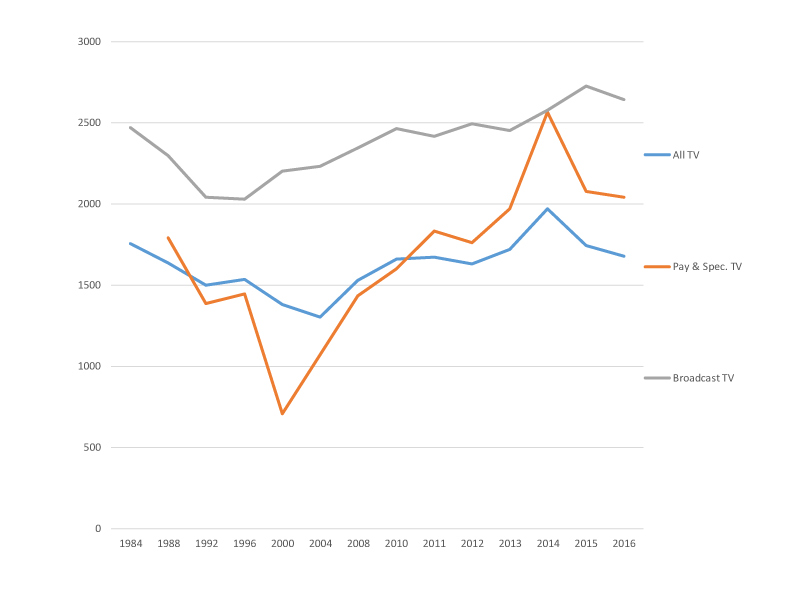

- there was a steep rise in TV concentration between 2010 and 2014 but the spin-off of some pay TV services by Bell and Shaw (Corus) and the rise of Netflix and other OTT services has helped turn the tide. The “big 5” TV operators’ took 81.1% of all TV revenue (including internet streaming) last year—down from 87% in 2014;

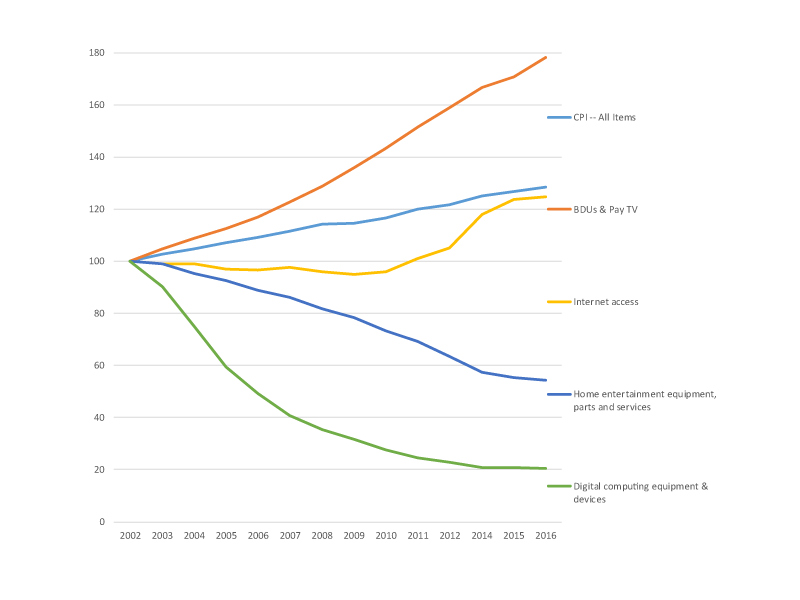

- the number of Canadian households with a cable TV subscription fell to 79.4% last year, down from 85% five years earlier but those losses have been offset by price increases in cable TV and broadband internet access that have outpaced the consumer price index by large margins;

- combined, Bell and Shaw (Corus) accounted for nearly half of the entire television universe (e.g. television distribution and services) by revenue as well as 130 television stations and services in 2016;

- Netflix replaced Quebecor as the 5th largest TV player last year with an estimated revenue of $534.1 million. Smaller TV operators such as DHX, Stingray, Blue Ant, Channel Zero, APN, V Interactions and CHEK have benefitted from these openings. However, their combined market share last year was significantly less than Astral Media’s alone on the eve of its take-over by Bell in 2013 (7.6%);

- Canadians get their news from a wide plurality of internet news sources, both old (CBC, Postmedia, Toronto Star, CTV) and new (Huffington Post, Buzzfeed), as well as domestic and foreign (BBC, Yahoo!-ABC, Guardian, New York Times);

- The scale of vertical integration amongst the “big 4” vertically-integrated giants in Canada more than doubled from 2008 to 2013. In 2016, Bell, Rogers, Shaw (Corus) and Quebecor accounted for 55.6% of the nearly $80 billion industry—nearly four times higher than vertically integrated companies’ share of the network media economy in the US;

- diagonal integration is where mobile wireless, wireline, ISPs and BDUs are owned by one and the same player, and is extensive in Canada as well, whereas in many countries there are stand-alone mobile network operators (MNOs), such as T-Mobile or Sprint in the US, or 3 in the UK, and Vodafone in many countries. The last stand-alone mobile wireless company in Canada–Wind Mobile–was acquired by Shaw in 2016;

- Vertical and diagonal integration tend to dampen competition between different ‘modes of communication’, raise prices, limit the size of monthly data caps, promote the use of zero-rating schemes that challenge the precepts of net neutrality (i.e. common carriage), etc. The use of data caps and zero-rating turns carriers into editors, or gatekeepers, and tilts the ‘model’ of the evermore internet- and mobile wireless-centric media universe towards a logic of integration, control and “walled gardens” vs “the open internet”.

- In recent years, the CRTC has rediscovered media concentration and taken steps to do something about it in a series of landmark rulings: e.g. its Mobile TV, Talk TV, regulated wholesale mobile wireless and wireline decisions, and last year’s “zero-rating” decision that girded the already strong “Net Neutrality” framework in Canada. Common carriage (or “net neutrality”) is crucial in a context where high levels of vertical integration obtain, although it does not turn on the point. Whether the Commission’s new chair, Ian Scott, will continue to hold the line in this regard, it is still too early to tell;

- Incumbent companies have flooded the courts with appeals of CRTC rulings and petitioned the Liberal Government to overturn others. Such efforts have been mostly unsuccessful. With the Telecommunications Act and Broadcasting Act slated for review, among the many policy initiatives underway, the years ahead will be critically important in terms of shaping how the network media economy will develop over the long-run.

The Canadian Media Concentration Research project is directed by Professor Dwayne Winseck, School of Journalism and Communication, Carleton University. It is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and has the mission of developing a comprehensive, systematic and long-term analysis of the media, internet and telecom industries in Canada.

Professor Winseck can be reached at either dwayne.winseck@carleton.ca or 613 769-7587 (mobile).

Acknowledgements:

Special thanks to Ben Klass, a Ph.D. student at the School of Journalism and Communication, Carleton University, and Lianrui Jia, a Ph.D student in the York Ryerson Joint Graduate Program in Communication and Culture, for assistance with the data collection and preparation of this report. Ben also made substantive contributions to the analysis and discussion of wireless services in Canada, and by lending a keen editorial eye to early drafts of this report.

Also, thanks to Sabrina Wilkinson, a graduate of the School of Journalism and Communication at Carleton University and now at Goldsmiths University in the UK, also offered valuable contributions to the sections on the news media and to Sarah Green of SiLK Web Solutions for help with the preparation of the various tables and figures and for maintaining the CMCR Project database and website.

Introduction

This is the second of two annual reports that review current developments and long-term trends in the telecoms, internet and media industries in Canada. Building on the first report in this series that examined the general economic conditions and trends within these industries, this second report zeroes in on another simple but profoundly important question:

have telecom, internet and media markets become more or less concentrated over time and how do we know one way or another?

This question is surprisingly difficult to answer because the issue is highly politicized and good data is hard to come by. As Philip Savage observed nearly a decade ago, debates about media concentration in Canada “largely occur in a vacuum, lacking evidence to ground arguments or potential policy creation either way”. That still holds true.

To help address these problems, this report analyzes concentration trends across the largest sectors of the telecoms, internet and media industries in Canada between 1984 and 2016: wireline and mobile wireless, internet access, television distribution (cable, satellite & IPTV), specialty and pay TV, internet streaming TV, broadcast TV, radio, newspapers, magazines, search engines, social media, internet news sources, internet advertising, desktop and mobile browsers, and desktop and smart phone operating systems—the core elements of what we refer to as “the network media economy”.

Each of these media sectors is examined on its own, and then they are grouped together into three more general categories: carriers/platforms; media content; and internet media. At the end, they are all grouped together to give us a view of the whole telecoms, internet and media landscape. Two common tools—concentration ratios (CR) and the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI)—are then used to assess the trends one way or another.

This research is conducted independently thanks to funding from SSHRC. As part of our mission of contributing to public knowledge and discussion of these issues we make all the data workbooks behind our reports available here and, for the first time this year, through the Scholars Portal Dataverse—a project spearheaded by a consortium of university libraries that aims to give scholarly research and writing a reliable home. Earlier versions can be found here, here, here, here and here). Anyone can freely use these reports and data sets for non-commercial and educational purposes based on the Creative Commons license.

Is Concentration Really a Problem: Four Schools of Thought

As our last report shows, the total size of the network media economy has more than quadrupled in size from $19.4 billion in 1984 to $79.3 billion last year. During this period, new segments have been added to our model of the media economy: mobile wireless, internet access, internet advertising as well as pay and internet streaming TV services, for example.

Currently, four hundred hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute; there were about 5.3 million Netflix subscribers in Canada last year; roughly 22 million Canadians had a Facebook account and many rely on it to get and share “the news”; expert blogs abound and whistle-blowers can and do set the news agenda; millions of websites are a click away; 689 TV services were authorized for service in 2016 and there were 1019 radio stations and 84 paid daily newspapers;[1] just over three-quarters of Canadians have a smartphone; access to a world of ideas (encompassing the best and the worst humanity has to offer) is just “a click away”. Canadians use all kinds of different information and communications technologies extensively: how can media and internet concentration possibly be a problem in this context of abundance?

In light of these realities, the first, and probably the most prominent, school of thought argues that if there was ever a golden media age, this is it (Thierer & Skorup, 2014). MIT Professor Ben Compaine (2005) offers a terse one-word retort to anyone who thinks otherwise: Internet. Media consultant Ken Goldstein argues that the pressing issue today is media fragmentation, not concentration (see here and here). It’s time for media companies to bulk up to compete, he thinks.

Large media conglomerates such as BCE tend to hold similar views: critics allege that media concentration is high, but the evidence “regardless of the metric employed—proves otherwise” (Bell, para 46). Think tanks like the Montreal Economic Institute, Fraser Institute, MacDonald Laurier Institute and C.D. Howe Institute offer a steady stream of reports and policy briefs fleshing out the arguments—which, in this author’s view are too often dutifully covered by the press without alternative and independent views getting similar treatment.

From this perspective, we are witnessing a battle of “the Stacks”. Vertical integration between telecoms companies and TV service providers is an integral part of dynamic competition and it is not only to be expected but welcomed because consumers like bundled services, while companies compete intensely not just on individual services but the whole bundle. From this view, any attempt to shackle telecoms and media companies with ownership restrictions will put them at more of a disadvantage as they increasingly compete with global digital media behemoths like Google, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, Facebook, and so on (Public Policy Forum, 2017; Skorup & Thierer, 2012). Bell underscores the point in its 2015 Annual Report: “digital advertising revenues . . . [were] lower . . due to [the] continued shift of advertising dollars to global players like Google and Facebook” (p. 68). In this view, competition does not just occur between providers of substitute goods, but across an entire ecosystem of related digital goods and service that some refer to as the “modular Internet” (Eisenach, 2016).

As proponents of this view see things, in the “digital ecosystem” there are telecoms operators on one side and “the stack”[2] ruled by Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Microsoft (GAFAM) on the other. Each of them has moved up and down the stack, significantly diversifying their operations. Their activities now include not only, popular search engines, social media sites, online retail options, and software but a hierarchically organized stack that also includes, for instance, operating systems (e.g. Android, iOS), data centres (Amazon Web Service, with Microsoft’s Azure, Apple’s own data centres, Google Cloud), and even the fibre optic cables—overland and underseas—that carry much of the world’s internet traffic and which even Netflix now depends heavily upon to meet its gargantuan-scale needs for data storage and to bring its services closer to its subscribers’ doorstep. Amidst this “battle of the stacks”, many in this first school believe that focusing on “telecoms” and “media” is akin to looking at the future through the rearview mirror.

Think tank scholars and corporate consultants such as Jeffrey Eisenach who tout these ideas together with a radical brand of free market fundamentalism are also being regularly flown into Canada for industry conferences and as hired experts at CRTC hearings (see here). While such ideas were once the preserve of right wing, fringe institutes in the US they have since been swept into power with Eisenach and a few others serving as telecoms policy advisors to the Trump Administration. And those ideas are also being woven into the circuit of respectable views in this country for the reasons just observed (also see here). Such views have even made odd-bedfellows with a kind of resurgent cultural nationalism amongst many people in the “creative industries” who fear—not without cause—the internet hyper-giant juggernaut.

The lobbying agenda around these issues has also heated up in recent years. The C.D. Howe Institute, for instance, urges the Trudeau Government to do away with outdated regulation and unshackle the telecoms-internet and media operators to compete amongst themselves and with the global internet giants. Whatever dominance they might gain will be transitory, they say, channeling the ideas of Joseph Schumpeter (1943). Old laws need to be dismantled and new ones fit for new times adopted. A key component of this view is that most oversight should be shifted to general principles of competition law, while the CRTC’s sails need to be trimmed. A recent MacDonald Laurier Institute report by former CRTC Vice Chair Len Katz and Institute senior fellow Sean Speer exemplifies this position. The consequences of not doing so could jeopardize the incumbents’ attempts to invest in our future, they argue, and whatever gains consumers might achieve will be lost down the road as the next generation of broadband capabilities and a new era of television and entertainment are sacrificed on the alter of short-term expediency. Government must take the long view, they intone, rather than pandering to short-term populist politics (see e.g. the Fraser Institute, Montreal Economic Institute, C.D. Howe Institute, MacDonald Laurier Institute).

Seen from another angle, however, these reports’ intransigent rhetoric of futility, perversity and jeopardy sounds a lot like the “rhetoric of reaction . . . in which conservative public figures, thinkers, and polemicists have been arguing against progressive agendas and reforms for two hundred years” (Hirschmann). Rather than contributing to a genuine discourse about the relationship between markets, business and economics, their real goal seems to be aimed toward disarming governments from doing what they are supposed to do: govern in the public interest.

A second school quantitatively analyzes reams of media content to see how changes in media ownership might affect content, particularly in relation to the issue of bias. This body of research is often driven more by the ideological predilections of its practitioners, however, with those on the left typically finding that ownership consolidation reinforces a conservative bias in the media while those on the opposing side find that consolidation empowers media conglomerates to achieve laudable economic and democratic goals. The best of this kind of research tends to find that the evidence on the matter is “mixed and inconclusive”—a result that has stayed remarkably consistent for decades (here and here).

To my mind, however, reducing the questions to whether concentration plays to good or ill “effects” is like trying to draw a camel through the eye of a needle. Even the most judicious of such research proceeds as if change in content is the only concern worth reflecting on or, as Todd Gitlin put it in a classic essay on media effects research, as if “no effect” might not be better seen as preserving the status quo. If so, that would be a significant problem in its own right.

A third school includes critics of media, internet, wealth, and corporate concentration such as Robert McChesney (2014). McChesney does not deny that the digital revolution is changing the world, but emphasizes an often overlooked fact: the core elements of the internet are no less prone to concentration than media in the past. In his classic book The Media Monopoly, Ben Bagdikian also argued that the number of media firms in the US that account for most of the revenue plunged from fifty to just five between the early 1980s and the early 21st Century. Canadian critics decry what they see as similar trends, and the debasement of news and the political culture of the country that has ensued as a result (here and here).

Critics also see the internet as draining money away from the media and entertainment industries—newspaper advertising especially—and into the coffers of Google, Facebook, Amazon, and so on. McChesney, however, does not lament the loss of advertising-sponsored journalism. Instead, he stresses the fact that the diversion of ad dollars away from journalism to the internet giants exposes a fundamental truth about the news: it is a public good, and most people don’t want to pay full freight. Consequently, the number of daily newspapers and full-time journalists is plunging and under-employed journalists are flocking to public relations in droves. Similar trends apply to Canada, but have lagged behind the US by a couple of years (see the last report on this point). Now is the time to recognize this forthrightly and turn to what the United States did in copious amounts throughout the first century-and-a-half of its existence, and that European countries and, to a lesser extent, Canada, continue to do: subsidize the news as the public good it is—on normative and economic grounds (also see Picard & Pickard, 2017).

Other critics of the US internet giants, such as Joseph Taplin’s Move Fast and Break Things and the Public Policy Forum’s Shattered Mirror report, converge with their leftist critics on this point. Indeed, a renaissance of the anti-monopoly tradition is arising from multiple directions that cuts across left-right political lines with Amazon, Facebook, Google, and so forth, in its sights. A diverse range of concerns underpins this revival, including critiques of the blackbox nature of internet giants’ platforms and businesses (Pasquale); the possibility that lush profits in one market (e.g. Amazon’s cloud services division) are being used to cross-subsidize razor thin profits (or none at all) in other markets to crush existing competitors and deter new ones from emerging (Khan; Srnicek); the use of price discrimination not to benignly enhance efficiency, as its advocates claims, but to discriminate between those who will be served and those who won’t—all in ways that are unfair and opaque; a desire to rein in the unlimited strip mining of personal and public data to protect privacy, reputation and socio-cultural norms like trust that underpin viable markets, society, democracy and civilization as a whole (Pasquale; Zuboff); concerns that “fake news” is not a random fluke but an expected byproduct of the internet giants’ business model and dominant stature in the market and society (Tufecki); the crisis of journalism and the media, culture and entertainment industries (McChesney; Taplin) and so on (also see The Economist, Bloomberg, Fortune, Vox and Wired).

A fourth school—and one that I largely align with–agrees with the first school that the shift from the industrial media of the 19th and 20th centuries to the digital, internet-centric media of the 21st Century entails enormous changes. This ongoing shift has, in turn, unleashed a “battle over the institutional ecology of the digital environment” (Benkler, 2006, ch. 11), with the broad contours of what is to come up for grabs. This perspective is also informed by the idea that the history of human communication is one of recurring ‘monopolies of knowledge” (Innis, 1951) and oscillations between consolidation and competition (John, 2010; Babe, 1990). Seen from this angle, it would be hubristic—or naïve—to think that our times will be any different (Noam, 2016, Benkler, 2006; Wu, 2010; Crawford, 2012).

From this perspective, the core elements of the networked digital media may actually be more prone to concentration than was the case for traditional media, because digitization magnifies economies of scale and network effects in many areas: mobile wireless (Rogers, BCE, Telus), search engines (Google, Bing, Yahoo, DuckDuckGo), Internet access (ISPs), music and book retailing (Apple and Amazon), social media (Facebook), browsers, operating systems, and access devices (Apple, Google, Nokia, Samsung). At the same time, however, digitization and the internet reduce barriers to entry in other areas, allowing many small players to flourish. A two-tiered digital media system is emerging, with many small niche players revolving around a few enormous “integrator firms” at the centre (Noam, 2016; Wu, 2010).

Reflecting on the results of a thirty-country study, Noam (2016) observes that concentration levels for mobile wireless and other “platform media” are “astonishingly high” and that while the data for content media is mixed, the trend is an upward direction (see especially chapter 38, pp. 1307-1316). Understanding where Canada fits within this context—that is, does it rank high, low or in between by international standards on the issue of media concentration—is the key purpose of this report.

The “fourth school” shares some similarities with the critical school in its insistence that core elements of the network media economy and internet are no less prone to concentration than previous media. However, it does not see concentration as inevitable. In fact, it takes clashes between the “tech titans” and “telecom behemoths” as critically important for two reasons: first, they are examples of how different factions of business battle one another not just within markets but for access to capital investment, influence over policy, and for wealth and prestige as well as political and cultural clout. The attention paid to dynamic competition by the “fourth school” also sets it apart from “third school” critics who tend to see markets in more monolithic terms. In this sense, it is closer to the Schumpeterian views of the market fundamentalists in the first school, while also retaining a more appreciative role regarding the complexity of markets and the contingency of outcomes that are often painted as inevitable in retrospect (“history is written by the winners…”).

It also sees cross-cutting forces at work that vary by media, time and place. Consequently, much more attention is given to empirical evidence and the details of media companies and markets in comparison to what we usually find in critical approaches or those who think that things are just fine.

The “fourth school” also rejects the insinuation that the alternative to the Schumpeterian dynamic “clash of titans” is a static and anachronistic view of competitive markets. Unlike the market fundamentalists, it sees these clashes as constitutive of modern capitalism and the idea that we should accept this phenomenon as inevitable and consequently beyond investigation is a fantasy. Lastly, it rejects Schumpeter and the market fundamentalists’ disdain for people’s knowledge, the publics’ myriad interests, and democracy. Indeed, the extent to which neo-Schumpeterians skirt his elitism and disdain for democracy is astonishing given that the issues here are not just about any old set of markets, technology and policy but communications. The approach taken here, in contrast, sees the market as a means to an end and markets as being constituted by rules and laws forged in the hurly burly of politics and all the complexity of society. Those rules and laws will vary by time, place and media, moreover. In a democracy, the first rule of governments is not to shield themselves, technology and/or markets from the public and people’s interests but to govern in the name of those interests. In other words, these discussions are fundamentally inseparable from concerns with human well-being and democracy. The so-called “fourth school” strives to take a large and complex view of all such matters, while insisting on the need to keep a sharp eye on both the details and the broad sweep of the nascent “digital media age” (see Schumpeter, 1943/2010; Held, 1987; Keane, 2009; Habermas, 1985; Habermas, 1996).

Why Media Concentration Matters, or Who Cares?

The more that core elements of the networked media economy are concentrated, the easier it is for dominant players to use the control and influence over various layers and elements of “the stack” to blunt the sharp edges of competition (see here, here, here, here and here). Large companies straddling the cross-roads of society’s communications also make juicy targets for those who would enroll them in efforts to curb piracy, suppress “fake news”, filter and block adult content, serve the machinery of law enforcement and national security, and to promote cultural policy aims (see here, here, here, here, here and here). To take one notable example, the extent to which Google has been leveraged by copyright interests and governments to disable links to materials that are claimed to infringe copyright, remove offensive content, and disclose users’ information has soared in the last half-decade is an excellent example of this, as the company’s annual Transparency Report reveals.

In sum, the more concentrated the digital media giants are, the greater their capacity for mischief. Some concrete examples include efforts to:

- turn market power into gate-keeping power and moral authority by regulating which content and apps gain access to their operating systems and online retail spaces and which do not. Apple’s rules restricting adult content availability on iTunes and decision to remove a fund-raising app for Wikileaks on the AppStore illustrate are examples of this;

- discourage the use of virtual private networks and anonymizing techniques to reinforce the sanctity of national media content rights markets and the role of advertising in them but at the expense of making people’s media activities more identifiable, locatable and targetable (Ellis, 2016);

- be enrolled in efforts to further cultural policy goals by applying a levy on telecoms and internet access providers to support Cancon and other cultural policy goals, or to use deep packet inspection techniques to discover and prioritize Canadian content while discouraging access to “less desirable” content (Geist, 2015; Taylor, 2015);

- set the terms for owning, controlling, syndicating and selling advertising around user created content (Google, Facebook, Twitter) (van Couvering, 2011; Fuchs, 2011);

- use the media outlets they own in one area to promote their interests in another, as former Vice President Media at Bell, Kevin Crull, did several times before being ousted for meddling in CTV’s new coverage (see Telus intervention in Bell Astral, 2.0 pages 4-6 and here, here, here and here);

- set the terms for the distribution of income to musicians, journalists and media workers, and authors (Google, Apple, Amazon);

- set de facto corporate policy norms governing the collection, retention and disclosure of personal information to commercial and government third parties, as was the case with Bell’s Relevant Ads Program that was withdrawn under pressure from complaints filed with the Office of the Privacy Commissioner and the CRTC.

Good analysis adjusts to new realities, but in a way that does not dismiss long-standing concerns out-of-hand. This is the approach that we strive to follow. For example, consider the fact that in the 2011 Canadian federal election every newspaper (except the Toronto Star) that editorially endorsed a candidate for Prime Minister touted Harper. Indeed, 95% of editorial opinion expressed stumped for Harper—roughly three times his standing in opinion polls at the time and the results of the prior election.

In the 2015 election, seventeen dailies representing 71% of the editorial opinion expressed lined up behind the ruling Conservatives.[3] The owners of the Postmedia Group, most notably, directed the ten dailies that comprise its national chain of papers, and the six major Sun dailies in London, Toronto, Ottawa, Winnipeg, Calgary and Edmonton that it acquired in 2015, to publish an editorial endorsement of Steven Harper for Prime Minister (55% of expressed editorial opinion). The action ran roughshod over with the long-standing convention in journalism circles whereby local editors write their own editorial endorsements, and this raised the hackles of some of the chain’s journalists and editors but with no discernible effect. The ‘editorial endorsement from headquarters’ also broke Postmedia’s pledge to the Competition Bureau to keep the editorial lines of the Sun papers it had just acquired separate from those it already owned, but this too was met with impunity. The Globe and Mail took the odd position of endorsing the Conservatives but not Harper—meaning that the editorial support for the Conservatives was roughly two-and-a-half times their low 30 percent standing in the polls and final voting results.

There were, however, more cracks in the wall of editorial opinion in the 2015 federal election. For example, Torstar’s Toronto Star, Hamilton Spectator and the Guelph Mercury (21% of expressed editorial opinion) both endorsed the Liberals, as did La Presse (Power Corp) (8% of expressed editorial opinion) and the Charlottetown Guardian (Transcontinental) (1% of expressed editorial opinion). Le Devoir cast its lot with the Bloc Québécois (representing 2% of expressed editorial opinion) (see here for a fuller treatment of this issue). No major daily endorsed the NDP.

As this discussion suggests, ultimately, talk about media concentration is a proxy for larger conversations about the shape of the mediated technological environments through which we communicate, know and express ourselves in the world, consumer choice, freedom of the press, citizens’ communication rights and democracy. Of course, such discussions must adapt to new realities, but the advent of digital media does not render them irrelevant one bit In fact, it may make them more relevant than ever (Baker, 2007; Noam, 2009; Peters, 1999).

Methodology: How Do We Know if Media Concentration is Intensifying or Declining?

Measuring media concentration begins by setting out the media industries to be studied, as done at the outset of this post. Revenue data for each of these sectors, and for each of the firms within them with over a one percent market share, is then collected and analyzed. This handy dandy list of sources and others listed here were used.

Each media sector is analyzed on its own and then grouped into three categories, before scaffolding upwards to get a birds-eye view of the whole network media ecology: (1) platform media; (2) content media: (3) online media. Results are analyzed from 1984 to 2016, with an eye to capturing changes over time. Lastly, two common tools—Concentration Ratios (CR) and the Herfindhahl-Hirschman Index (HHI)—are used to depict concentration levels and trends within each sector and across the network media ecology as a whole.

The CR method adds the shares of each firm in a market and makes judgments based on widely accepted standards, with four firms (CR4) having more than 50 percent market share and 8 firms (CR8) more than 75 percent considered to be indicators of media concentration (see Albarran, p. 48). The Competition Bureau uses a more relaxed standard, with a CR4 of 65% or more possibly leading to a deal being reviewed to see if it “would likely . . . lessen competition substantially” (p. 19, fn 31).

The HHI method squares the market share of each firm in a given market and then totals them up to arrive at a measure of concentration. If there are 100 firms, each with 1% market share, then markets are thought to be highly competitive (shown by an HHI score of 100), whereas a monopoly prevails when one firm has 100% market share (with an HHI score of 10,000). The US Department of Justice embraced a revised set of HHI guidelines in 2010 for categorizing the intensity of concentration. The new thresholds are:

HHI < 1500 Unconcentrated

HHI > 1500 but < 2,500 Moderately Concentrated

HHI > 2,500 Highly Concentrated

At first blush, these higher thresholds seem to dilute the earlier standards that had been set back in 1992. While this may be true, the new guidelines can be seen as being even more sensitive to reality and tougher than the ones they supersede.

This is because they give more emphasis to the degree of change in market power when ownership changes take place. For instance, “mergers resulting in highly concentrated markets that involve an increase in the HHI of more than 200 points will be presumed to be likely to enhance market power”, observes the DOJ (emphasis added, p. 19).

Second, markets are defined more precisely based on geography and the details of the good or service at hand versus loose amalgamations of things based on superficial similarities. This is critical. It distinguishes those who would define the media universe so broadly as to put photocopiers and chip makers alongside ISPs, newspapers, film and TV and call the whole thing “the media” (e.g. Skorup & Theirer; Compaine). In contrast, the scaffolding approach we use analyzes each sector before moving to higher levels of generality until reaching a birds-eye perspective on the network media as a whole. It is important to note that this method allows us not only to draw general conclusions from the birds-eye perspective, but also to analyze developments at a much more precise level. Approaching the subject from multiple vantage points allows us to undertake integrated empirical analysis based on observations of dynamics at all levels, something that is simply not possible (and certainly would not be credible) without precise and meticulous attention to specific detail.

Third, the new guidelines turn a circumspect eye on claims that enhanced market power will be good for consumers and citizens because they will benefit from the increased efficiencies that result. What is good for companies is not necessarily good for the country (see Stucke & Grunes, 2012; Mazzucato, 2014).

Lastly, the new guidelines are emphatic that decisions turn on “what will likely happen . . . and that certainty about anticompetitive effect is seldom possible and not required for a merger to be illegal” (p. 1). In practice this means the goal is to nip potential problems in the bud before they happen. It also means that experience, the best available evidence, contemporary and historical analogies as well as reasonable economic theories form the basis of judgment, not deference to impossible (and implacable) demands for infallible proof (p. 1).

These assumptions overturn three decades of Chicago School economic orthodoxy and its grip on thinking about market concentration (see Stucke & Grunes, 2012; Stucke & Grunes, 2016; Posner, 2011). The focus is no longer just on horizontal integration within a market but also in terms of vertical and diagonal integration across markets. The emerging view also goes beyond assessing matters mainly in terms of potential consumer harms and benefits (e.g. how do we deal, for example, with “free” services like those on offer from Google or Facebook? How do mergers affect relationships among competitors or complementary goods and services?). Freed from a half-century long orthodoxy, and subordination of policy and politics to conservative economists, think tanks and judges, the new guidelines in the US set a tough hurdle for those with the urge to merge. It is just this kind of thinking that killed the bid by AT&T—the second largest mobile wireless company in the US—to acquire T-Mobile, the fourth largest, in 2011, for instance (also Stucke & Grunes, 2012). Similar concerns also loom at present as AT&T prepares a takeover bid for Time Warner.

For years, the toughening stance on concentration issues in the US and EU had largely passed Canadian regulators by but that has been changing recently. The CRTC’s tepid stance on such matters was exemplified by the Commission’s 2008 Diversity of Voices policy, which established a static measure for reviewing mergers that has no sense of trends over time or capacity to analyze the drift of events across the media. Not surprisingly, the Diversity of Voices policy has done nothing to stop consolidation within the broadcasting industries let alone between them and the telecoms and internet industries, as the evidence below demonstrates.

In contrast to the CRTC, the Competition Bureau does at least draw selectively from the US HHI guidelines. While it does not use the HHI thresholds, it does focus on “the relative change in concentration before and after a merger” (emphasis added, p. 19, fn 31).

The CRTC began to tiptoe in a different direction in 2012, and several decisions since suggest that it has rediscovered market power and the will to do something about it:

- the Mobile TV decision in which it shored up common carriage (network neutrality) principles by preventing mobile wireless carriers from unjustly discriminating against television programs and other types of communications delivered over the internet in favour of their own services. In doing so it effectively banned the nascent practice of zero-rating whereby some content service chosen by the carriers do not count towards your data caps, while similar types of services do. The decision is crucial because it reaffirms the principle that telecoms service and internet access providers are carriers not editors, a distinction that was upheld when the Federal Court of Appeal rejected an appeal of the Mobile TV decision by Bell;

- the Talk TV decision requiring the adoption of skinny basic cable TV packages and the unbundling of TV channels so that they are offered fully on an ala carte base by 2016;

- the mandated wholesale wireless framework designed to enhance competition in mobile wireless services by regulating wholesale roaming rates and other factors which affect the viability of would-be rivals such as Videotron and Wind (now Freedom Mobile after a 2016 takeover by Shaw);

- the mandated wholesale wireline decision that extends regulated wholesale access to the incumbent telecom and cable companies’ fibre-to-the-premise networks to help encourage competition in the retail broadband internet market while ensuring that rivals such as TekSavvy, Distributel, Primus and others can still compete as technology shifts from copper and coaxial-based networks to fibre-based facilities – all of which the incumbent telecoms and cable companies have fought tooth-and-nail, and which Bell has appealed to the Liberal Cabinet to overturn.

Several key principles underpin these decisions. One is the CRTC’s recognition that the “incumbent carriers continu[e] to dominate the retail Internet access services market” (CRTC, 2015-326, para 125). The wholesale mobile wireless decision arrived at the same conclusion with respect to the wireless market (CRTC, 2015-177, paras 35, 72-74, 86-88). Moreover, there is “limited rivalrous behaviour” between the incumbents, the Commission observed with respect to fibre-based broadband access networks (CRTC, 2015-326, para 123). The Commission was especially blunt when it stated that whatever “competition that does exist today is largely, if not entirely, a result of regulatory intervention” (CRTC, 2015-326, para 123).

The upshot of this recent turn of events is two-fold: first, concerns for the harmful potential of market concentration and market power are not just conjecture, but have been found to be factually based and significant by administrative tribunals such as the CRTC and the courts. Second, in the face of such realities, the regulator has stiffened its spine and acted in a manner that marks a clear break from the “regulatory hesitation” that has defined so much of the regulatory culture in Canada in the past (Berkman, 2010, p. 163).

Whether this will continue to be the case is a crucial issue. However, history and international experience teaches that in the face of intransigent and self-serving opposition from incumbents, only governments and regulators with a stiff spine and strong political can succeed in fostering more competition and improved developments in the communications and media fields (see, for example, Noam, 2013; Mazzucato, 2014; OECD, 2013, p. 23; Ofcom, 2012, pp. 67-68; Ofcom, 2012; Stucke & Grunes, 2012; Stucke & Grunes, 2016; US, DoJ, 2011; Berkman, 2010, pp. 162-168).

The Historical Record and Renewed Interest in Media Concentration in the 21st Century

While this regulatory about face may be new, a keen interest in media concentration is not. As a matter of fact, there has long been an abiding interest in the subject in Canada and the world over since the late-19th and early-20th centuries, even if it such interest ebbs and wanes over time.

In 1910, for example, early concerns with the ill effects of market concentration were registered when the Board of Railway Commissioners (BRC)—the distant cousin of today’s CRTC—broke up a three-way alliance between the countries’ two biggest telegraph companies—the Canadian Pacific Telegraph Company and the Great Northwestern Telegraph Company (the latter a division of the New York-based goliath, Western Union)—and the US-based Associated Press news wire service. Why?

It did this for much the same reasons that the CRTC gave in justification of the Mobile TV decision discussed a moment ago. That is, because carriers should not be editors who use their control over the wires (or spectrum) to decide who gets to speak to whom on what terms.

In this historical case, and in the face of much corporate bluster, the regulator was emphatic that while allowing the dominant telegraph companies to give away the AP news service for free to the leading newspaper in one city after another across the country might be a good way for the companies to attract subscribers to their vastly more lucrative telegraph business it would effectively “put out of business every news-gathering agency that dared to enter the field of competition with them” (1910, p. 275).

In a conscious effort to use telecommunications regulation (operating under the auspices of railway legislation at the time) to foster competing news agencies and newspapers, Canada’s first regulator, the BRC, forced Western Union and CP Telegraphs to unbundle the AP news wire service from their telegraph service. It was a huge victory for the Winnipeg-based Western Associated Press—the appellant in that case–and other ‘new entrants’ into the newspaper business as well. It was also the decisive moment when the principle of common carriage was firmly entrenched in Canadian communications policy and regulation (Babe, 1990).

In short, the BRC acted to constrain corporate behavior out of the conviction that concentration within the telegraph industry as well as vertical integration between telegraphs and news services would run counter to society’s broader interest in competitive access to communications and a plurality of voices in the press.

Throughout the 20th century, similar questions arose and were dealt with as the situation demanded. One guiding rule of thumb of communications policy, however, was that of the “separations principle”, whereby telecoms carriers–usually two of them (e.g. telegraph vs telcos in the early 1880s, the TransCanada Telephone System (TCTS) and CNCP for three-quarters of the 20th century, the telcos vs cablecos ever since, and the telcos’ consortium Stentor versus Rogers/Cantel in the early days of mobile wireless from 1985 until the mid-1990s) competed to carry messages from all types of users, and for all types of purposes–business, personal, governmental and broadcasting–but were prevented by law from directly creating, owning or controlling the messages that flowed across the transmission paths they owned and controlled.

A general concern also hung in the air in government, business, broadcasting and reformist circles that those who made communications equipment, or operated transmission networks, should not operate broadcast stations, make movies or publish newspapers, books, software, etc. That this was so could be seen, for example, when the original equipment manufacturing consortia behind the British Broadcasting Company in the UK and the National Broadcasting Company/Radio Corporation of America in the US, respectively, were ousted from the field in the 1920s during the remaking of these entities into the stand-alone broadcasters that they eventually became. Nor should telephone companies such as AT&T play an active role in the film industry, as was the case when, after having wired movie theatres across the US and the Hollywood production studios for sound, circa 1927, AT&T took on a larger role by financing and vetting films during the 1930s (see Briggs, 1995; Barnouw, 1966; Danelian, 1939).

The consolidation of broadcasting under the CBC in the 1930s brought private broadcasters into the core of the Canadian ‘broadcasting system’ from the get-go. The creation of the CBC also wiped out important local, foreign and educational voices, and even a small theatrical radio club in Winnipeg who were taking live theatre from the stage to the airwaves. In each case, it was the structure and organization of the communication/media system, and who owned what and in what proportions, that decided who got to talk to whom on what terms.

The separation of transmission and carriage from message creation and control was another principle that was worked out in a myriad of different ways. Aside from high-profile efforts to keep the telegraph companies out of the news business, and telephone companies out of broadcasting and the movie business, most of the time such issues were considered tedious, boring, and tucked away in obscurity in parliamentary papers, legislation and corporate charters.

Bell’s charter, for instance, prohibited it from entering into ‘content and information publishing services’, from radio to cable TV and ‘electronic publishing’, until the early 1980s, when more and more exceptions to the general rule were adopted. The same was true for other telcos, private and public, across the country, even though Manitoba and Saskatchewan began to lay fibre rings in a handful of provincial cities and to offer modest cable TV services in the 1970s (Babe, 1990; Winseck, 1998).

Media concentration issues came to a head again in the 1970s and early 1980s when three major inquiries were held: (1) the Special Senate Committee on Mass Media, The Uncertain Mirror (2 vols.)(Canada, 1970); (2) the Royal Commission on Corporate Concentration (1978); and (3) the Royal Commission on Newspapers (Canada, 1981). While these proceedings did not amount to much in the way of concrete reform, they left a valuable historical and public record.

Things lay dormant for more than two decades before springing to life again after a wave of consolidation in the late-1990s and at the turn-of-the-21st century thrust concerns with media concentration back into the spotlight. Three inquiries between 2003 and 2008 were held as a result: (1) the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage, Our Cultural Sovereignty (2003); (2) the Standing Senate Committee on Transport and Communications, Final Report on the Canadian News Media (2006); (3) the CRTC’s Diversity of Voices report in 2008.

Things have not let up since. Indeed, they have been on a high boil in recent years, with a non-stop series of reviews at the CRTC that will go a long way to shaping the emergent network media economy for decades, including, for instance: (1) Bell’s take-over of Astral Media, (2) the regulated wholesale access decisions affecting both the mobile wireless and wireline telecoms markets, respectively, (3) the Mobile TV decision and (4) a series of recent cases that have tested the extent to which vertically-integrated telecom-media giants like Bell, Rogers, Shaw and Videotron can leverage their control over networks to influence the content made available over those networks (for example, Videotron’s Music Unlimited case or the Rogers GamePlus and Hybrid Video-on-Demand decisions). Another landmark decision by the regulator early this year to effectively ban mobile carriers and other ISPs from “zero-rating” specific content or applications in a bid to distinguish their services from those of rivals is another key example on this score.[4]

Three Phases of Telecom, Internet and Media Consolidation and the Rise of Vertically-Integrated Telecoms and TV Companies at the Centre of the Canadian Media Universe

All of this is taking place, as I noted in the last report, within an ever more internet- and mobile-centric media economy that has grown immensely from $19.4 billion in 1984 to $79.3 billion last year.

The early years of that period (the decade between 1984 and 1996), were characterized by the emergence of new players across the media landscape and the growth of broadcast as well as pay and subscription television channels. In terms of ownership, existing players and a few newcomers, such as Allarcom and Netstar, cultivated the field.

During this period, television and radio broadcasters were often owned by companies whose interests lay in other, unallied areas, such as real estate, as with the BC TV and radio group Okanagan Skeena, or Molson’s Brewery, one of the founders of Netstar early in that entity’s history. These companies share of the market grew steadily until they were taken over by the larger players of their time. Overall, though, the general direction of events was towards more players and more diversity in television ownership.

When consolidation did take place in the 1980s and 1990s it was mostly among individual players in single media markets, i.e. horizontal integration. Conrad Black’s take-over of Southam newspapers in 1996 symbolized the times, as did the amalgamation of local and regional television ownership groups in the late 1990s to create several national commercial television networks under common ownership: CTV, Global, TVA, CHUM, TQS.

While weighty in their own right, these amalgamations did not have a big impact across the media. The CBC remained prominent, but public television was being eclipsed by commercial television as the CBC’s share of all resources in the television ‘system’ slid from 44 percent in 1984 to much less than half that amount today (17%).

Media conglomerates were not unknown (Maclean-Hunter was a good example), but they were not the norm. Bell was a diversified communications colossus, to be sure, but it was not in the media business proper, and was prevented by its charter and by law from being so.

In contrast to broadcasting and most other content media industries, concentration levels remained sky high in wireline telecoms, while new mobile wireless telecoms services were developed by two sets of competing firms: between 1983-1984, Rogers-Cantel was licensed by the Department of Communication to offer national wireless service, while 11 incumbent telephone companies (e.g. Bell Canada, Telus, MTS, Sastel) received licenses to provide competing services in their respective operating territories (Klass, 2015, pp. 58-61).

Gradual policy reforms characterized the 1980s and early-1990s, before a more concerted shift took place. Long distance competition was introduced in 1992, while two new national competitors in wireless followed in 1995 (Clearnet and Microcell), and then local telephone competition was encouraged in 1997. The Chretien Liberals also gave the green light for the telephone and cable companies to compete in one another’s turf in 1996. Concentration rates fell across the board, except in cable television distribution.

In general, telecoms competition moved slowly from the ends of the network into services and then deeper into the network infrastructure, as it had done in one country after another around the world, aided and abetted by strong government interventions that used interconnection and network unbundling rules, access to spectrum, wholesale pricing regulation, and market liberalization to actively spur on competition. Competition gained traction in the 1990s as a result but the trend was thrown into reverse by the dot.com crash in late-2000.

Whereas gradual change defined the 1980s and early-1990s, things shifted abruptly by the mid-1990s and carried on into the 21st century when three waves of consolidation swept across the telecom, internet and media industries. A flurry of highlights will help to illustrate the trends:

Wave 1: 1994 to 2000: Rogers’ acquisition of Maclean-Hunter (1994), but peaking from 1998 to 2001: (1) BCE acquires CTV and the Globe & Mail ($2.3b); (2) Quebecor takes over Videotron, TVA and the Sun newspaper chain ($ 7.4b) (1997-2000); (3) Canwest buys Global TV ($800m) and Hollinger newspapers papers, including National Post ($3.2b); (4) BC Tel, AGT, and Edmonton Tel were also amalgamated at this time, giving rise to Telus, which then acquired Clearnet for $6.6B, the largest acquisition in Canadian telecommunications history at the time)(2000).

Wave 2: 2004-2007: Rogers acquires Microcell ($1.4B) (2004). Bell Globemedia re-branded CTVglobemedia; BCE exits media business. CTVglobemedia acquires CHUM (Much Music, City TV channels and A-Channel). CRTC requires CTVglobemedia to sell City TV stations – acquired by Rogers (2007). Astral Media buys Standard Broadcasting. Quebecor acquires Osprey Media (mid-size newspaper chain)(2006). Canwest, with Goldman Sachs, buys Alliance Atlantis (2007) (Showcase, HGTV, BBC Canada and the biggest film distributor in Canada).

Wave 3: 2010 – 2015: Canwest goes bankrupt (2009-2010), its newspapers acquired by Postmedia and TV assets by Shaw. BCE reacquires CTV (2011) and bids for Astral Media in 2012, but fails to gain CRTC approval, before succeeded to do so in 2013. Bell sells Teletoon (TELETOON Retro, TELETOON Retro, TELETOON / TELETOON and the Cartoon Network), Historia and Séries+ to Corus (Shaw), the Family Channel, Disney Jr. and Disney XD to DHX media, and MusiquePlus and MusiMax to V Media, as well as ten radio stations to Newcap (5), Pattison (3) and Corus (Shaw)(2)—as the Competition Bureau and CRTC required as a condition of approval of Bell’s take-over of Astral media in 2013; Telus acquires Public Mobile (2013); Rogers acquires Mobilicity ($465M)(2015); Postmedia acquires Quebecor’s English-language papers (e.g. including the six Sun dailies, 27 small dailies and 140 community weeklies) (2015) (also see Competition Bureau approval), and Shaw acquires Wind (early 2016).

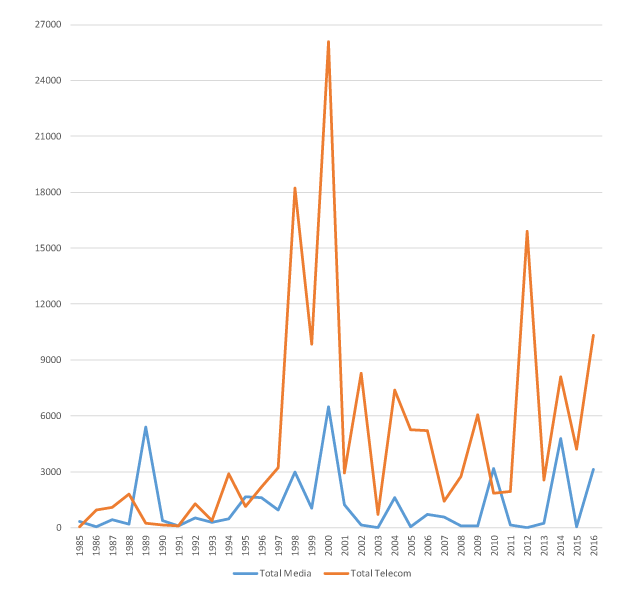

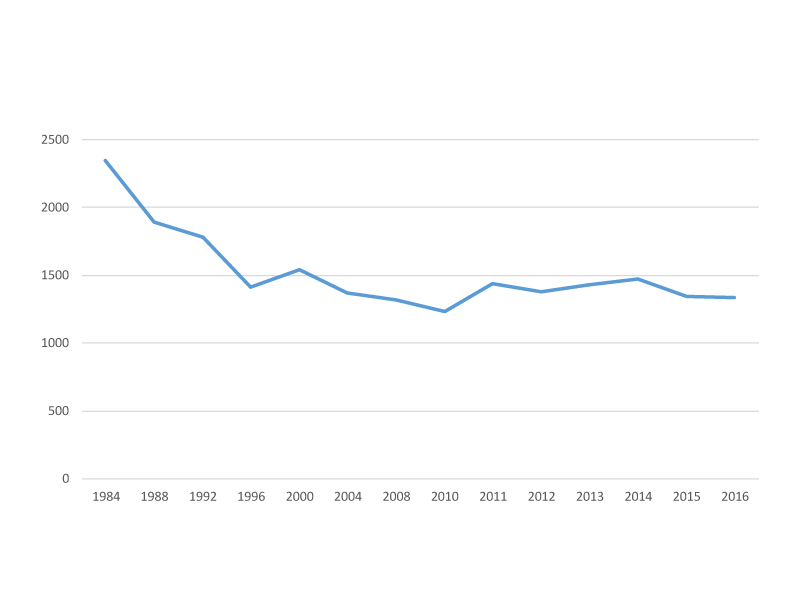

The massive wave of capital investment that drove consolidation across the telecom, media and Internet industries during these different phases, as illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Mergers and Acquisitions in Telecoms & Media, 1985–2015 (Mill$)

Sources: Thomson Reuters. Dataset on file with author.[1]

Mergers and acquisitions rose between 1994-1996 and spiked to unprecedented levels by 2000 but collapsed when the dot.com bubble burst. Consolidation regained steam between 2004 and 2007, plunged with the onset of the Global Financial Crisis (2007ff), and has been rising significantly since 2012. Once again, trends in the network media economy swiveled on those evident in the economy at large—a point that cannot be ignored but which too often is.

Consolidation in the telecoms industry had been modest in the latter half of the first decade of the 21st Century but rose significantly after Telus bought Public Mobile and Bell acquired the remaining stake in Bell Aliant that it did not already own in 2013 and 2014, respectively, while Rogers acquired (and then dismantled) Mobilicity in 2015. The Competition Bureau’s approval of Bell’s acquisition of MTS this year furthers the trend. It also calls into question the Bureau’s resolve on such matters given that its own analysis showed that oligopolistic behaviour by the big three national carriers—Bell, Rogers and Telus—is hobbling the availability of high quality, affordable mobile wireless services, especially in areas where there is no strong independent rival. Despite these findings, the Bureau approved the deal. Consequently, Bell’s take-over of MTS adds Manitoba to the list of provinces and regions without a strong independent operator (see our report opposing the deal).

Consolidation has also surged in recent years on the media side of things too, as Figure 1 illustrates. Shaw’s take-over of Global TV in 2010, with its suite of thirty specialty and pay TV channels and nine television stations, from Canwest (2010), kicked off the trend. Bell’s re-purchase of CTV (2011), acquisition of a joint-ownership stake (37.5%) with Rogers (37.5%) and Kilmer Sports (25%) in Maple Leaf Sports and Entertainment in 2012, and take-over of Astral a year later all fueled the trend (see the TV Services Ownership sheet in the CMCRP Workbook; BCE, Annual Report, p. 31). The latter set of deals turned Bell into the biggest TV and radio broadcaster in the country, with a suite of thirty broadcast TV stations, thirty-nine pay and specialty TV channels, and 105 radio stations in fifty-four cities nationwide.

Consolidation in the TV industry has been the result. More importantly, though, consolidation has yielded a specific type of media company that now sits at the apex of the network media universe in Canada: i.e. the vertically-integrated telecoms, internet and media conglomerate. Vertical integration has soared and is now very high relative to the past and to conditions in the United States and internationally. Figures 2 and 3, below, illustrate the steep increase in vertical integration occurred between 2008 and 2016, while Figure 5 (further down) offers a comparison with the state of affairs in the United States.

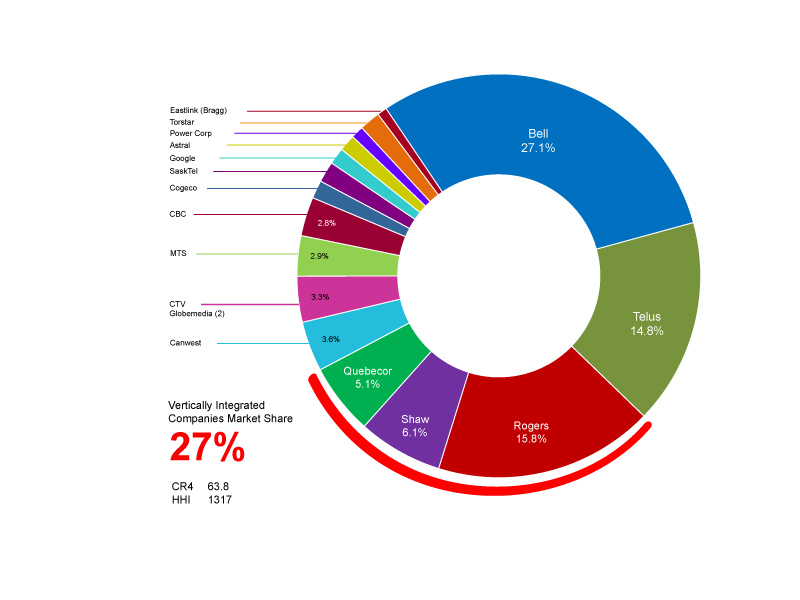

Figure 2: Vertical Integration and the Network Media Ecology, 2008

Sources: see the “Top 20 w Telecoms” sheet in the CMCRP Workbook.

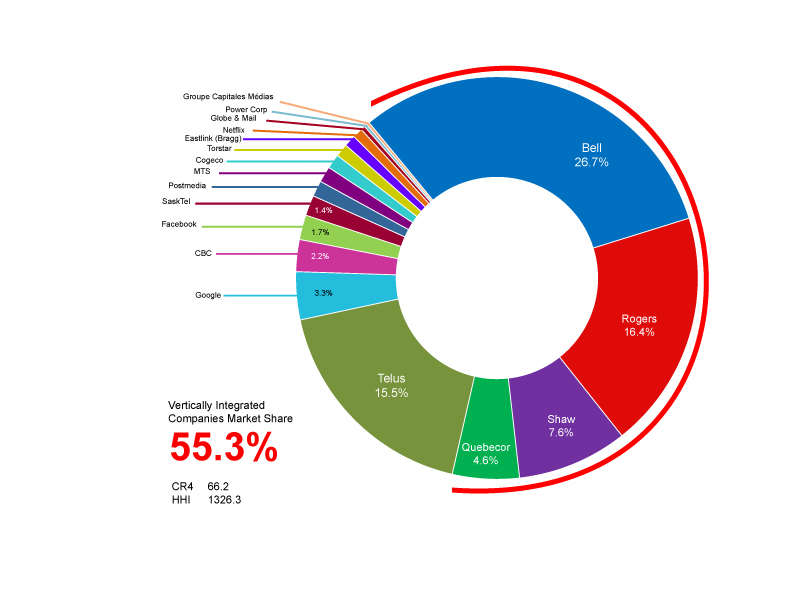

Figure 3: Vertical Integration and the Network Media Ecology, 2016

Sources: see the “Top 20 w Telecoms” sheet in the CMCRP Workbook.

As Figures 2 and 3 illustrate, in the span of half-a-decade, vertically-integrated companies’ share of the network media economy more than doubled. By 2016, four giant vertically-integrated conglomerates accounted for 55.3% of all revenue across the network media economy: Bell (CTV), Rogers (CityTV), Shaw (Global) and QMI (TVA), as Figure 3 shows.

These developments are important for several reasons. First, they distinguish the past from the present. Centre stage is currently occupied by four vertically-integrated telecoms, internet and media giants with a reach across the network media economy (one might also include Telus on account of its fast growing role in television distribution). Zero in on just telecoms and broadcasting, and the ‘big 5’ accounted for 80% of all revenue in 2016—up substantially from roughly two-thirds in 2010 (but down slightly from it’s all-time high two years ago).

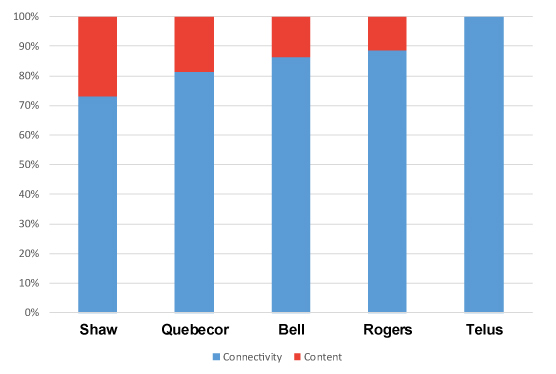

Second, these five companies’ collective control over communications infrastructure is the fulcrum of their business. Their stakes in content media, while extensive, are modest by comparison; Telus is not in the content business at all beyond buying rights for its Optik IPTV and mobile TV services. For Quebecor, Shaw, Bell and Rogers, 70-90% percent of their revenues flows from their control over bandwidth and connectivity rather than from content creation and exhibition. Figure 4 below illustrates the point.

Figure 4: Connectivity vs Content within Canada’s Vertically-Integrated Telecoms and Media Companies, 2016 (Ratio by Revenue)

Sources: see the “Top 20 w Telecoms” sheet in the CMCRP Workbook.

Another way to put this is that content media are largely ornaments on the carriers’ corporate edifice. They are strategically important but their real purpose seems to be to drive the take-up of the companies’ more lucrative wireless, broadband, and cable, satellite and IPTV services. The fact that Bell owns roughly half of the services on its Mobile TV roster, for example, illustrates the point: e.g. CTV, CTV News Channel, CTV Two, BNN, Comedy Network, Comedy Time, MTV, NBA TV, NFL Network, E!, RDS, RDS2 and TSN, TSN2, etc.

The CRTC has already examined some of the results of these kinds of consolidation on the carriers’ behaviour. For instance, in the Mobile TV case the Commission determined that Bell was using its control over the means of delivering television programming to confer an undue preference on its services at the expense of subscribers, rivals and independent sources of content available over the internet. Bell appealed the ruling to the Federal Court of Appeal, but its appeal was rejected in mid-2016.

Other cases similar to Mobile TV, however, have emerged one after another in a never ending game of regulatory whack-a-mole: see, for example, the complaint initiated by J. F. Mezei and the Public Interest Advocacy Centre against Videotron’s Music Unlimited, which was later rolled into the regulator’s review of “differential pricing practices” (the zero-rating proceeding), or the Commission’s Hybrid Video-on-Demand decision, Hybrid Video-on-Demand decision, or Bell’s appeal of the wholesale vertical integration code, to name just a few. The thread connecting them all is the extent to which content is being tied to carriage in ways that raise fundamental questions about the future of common carriage (“network neutrality”) and ‘the open internet’, and the role that concentrated network ownership plays in these developments.

Two rulings last year under then chair Jean-Pierre Blais dealt with these issues in a way that constituted significant wins for common carriage (“net neutrality”), competition and cultural policy. In one of them, the Commission found that Videotron’s Unlimited Music program ran afoul of Canada’s telecoms law by giving undue preference to subscribers of the company’s highest tier data plans over the rest of its customers and to the music services included in its offering such as Apple Music, Google Play, Spotify versus those that are available over the internet and public airwaves but left out Videotron’s Unlimited Music offering, e.g. the CBC and commercial radio stations.

The CRTC also combined the lessons of that ruling with its 2015 Mobile TV decision and interim events to develop a general framework that effectively bans wireless operators and ISPs from singling out content-based services and apps for special treatment such as zero-rating, whether on the basis of commercial agreements or otherwise. The framework also banishes pay-to-play schemes like those in the US where certain content providers or in-house affiliates like AT&T’s DirecTV “sponsors data” so that the internet traffic generated by the use of the service does not count against AT&T subscribers’ monthly data allotments.

These rulings are clear victories for common carriage in Canada. They are clear that the long-standing telecoms policy principle of common carriage still applies to internet access and mobile phones. The rulings also clarify the idea that, when offering access to the internet, carriers are not publishers or broadcasters. In short, the basic idea is that when it comes to the selection and use of content, apps and services that are made available over the internet and via mobile phones, citizen-consumer-subscribers are in charge rather than the carriers. Seen in this light, the rulings are victories for the open internet and the idea that it is people’s expressive and communication rights that come first in a democracy rather than those who own and control the networks upon which day-to-day life, society and economic activity depend.

The cases are also especially important in the Canadian context because they address a unique feature of the media in this country: the extremely high levels of vertical integration that exists between telecoms companies and media services, especially television services. Indeed, the levels of vertical integration that now prevail in Canada are not just high by our own historical standards, but also relative to those in the United States and internationally. High levels of concentration, exacerbated by the extreme scale of vertical integration, have been significant enabling factors to the parade of harmful business practices described above.

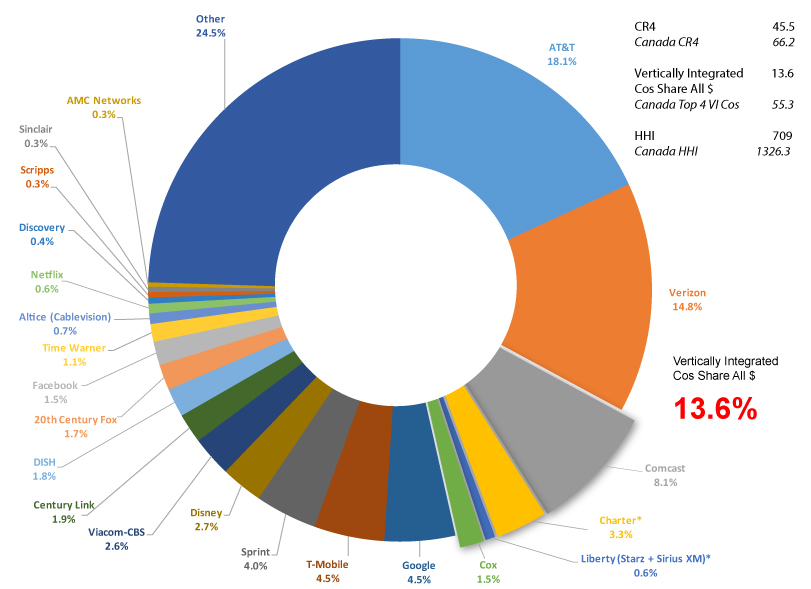

Figure 5 below illustrates the point with respect to the United States.

Figure 5: Top Telecom-Internet and Media Companies in the US, 2016 (Market Share)

Sources: see the “Top US Telecom + Mediacos” sheet in the CMCRP Workbook.

The contrast between the extent of vertical integration in Canada shown in Figures 3 and what prevails in the United States, as shown in Figure 5, is stark. The first thing that jumps off the page in Figure 5 is just how modest vertical integration in the United States is at less than one-quarter what it is in Canada (14% versus 55%, respectively).

Whereas, as we saw earlier, Bell, Rogers, Shaw and Quebecor stand at the apex of the network media economy in Canada, in the United States, the only comparable company is Comcast. Even then, it accounts for about 8% of the US media economy whereas Bell’s relative share of the Canadian market accounts for more than three times that amount (i.e. 27%).

Despite being separate legal companies, Charter and Liberty can also be considered to be a vertically integrated operator because of the common ownership interests that stand behind them. Charter is the fourth largest broadcast distributor in the US while Liberty owned the pay TV operator Starz (Animal Planet, Discovery, Encore, Black, Starz, Movieplex, etc.) and Sirius XM until December 2016 when it was sold it to the independent film studio Lion’s Gate. Probably not incidentally, given that on a stand alone basis its incentives would likely shift from helping to protect Liberty’s much larger cable interests to getting access to as many people across as many platforms as possible, just before its sale, Starz launched its own stand-alone internet streaming television service and mobile app that is available over the internet without a cable subscription.

Cox is the only other significant vertically-integrated company in the US. It is the sixth largest cable TV operator and owns a relatively small number of broadcast TV and radio stations. Add them all up and the three vertically-integrated operators account for just under 14% of the network media economy in the US, as mentioned above—just one-fourth the prevailing level in Canada. Take Charter and Liberty out of the picture because of the spin-off and sale of Starz and the figure falls to just 10%. In practical terms, there are really just two vertically-integrated companies in the US: Comcast and Cox, and their scale relative to the rest of the US media pales in significance to the influence that the vertically-integrated companies exert on the media landscape (and policy) in Canada.

Of course, some might argue that this ignores, for example, Verizon’s “blockbuster” take-over of Yahoo this year. To put things in perspective, consider that Yahoo’s worldwide revenue last year was $5.2 billion. Verizon’s revenue in the United States alone was $121 billion—twenty-five times that of Yahoo. In other words, Yahoo is something of a pimple on the backside of an elephant. To be sure, it is not inconsequential, but given its size relative to that of Verizon and that it relies almost exclusively on advertising dollars rather than “pay-per” subscriptions to mobile wireless, broadband internet and limited pay TV services that Verizon has, Yahoo is a minor addition bolted on to a much larger corporate edifice. In sum, Verizon’s ownership of Yahoo lacks both the scale and the scope necessary for it to be considered comparable to the operations of media conglomerates in Canada (or Comcast in the US) whose holdings reach not only vertically up and down the stack but across the TV, radio and production domains.[1]

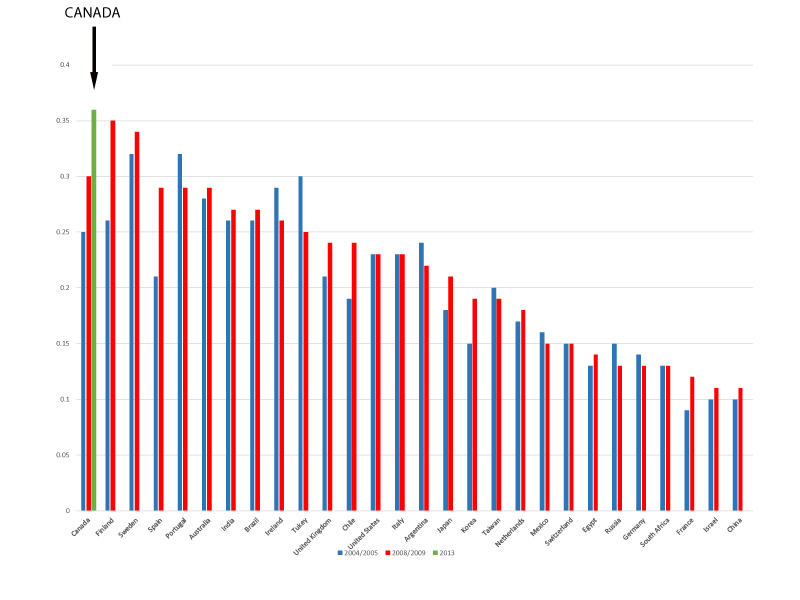

But returning to the Canadian context, that vertical integration and cross media ownership is exceptionally high in this country not just by historical and United States standards but also by international ones is depicted in Figure 6, below. It uses the most recent data available for the twenty-eight countries covered by the International Media Concentration Research Project and for Canada for the years covered by that project and 2013 in order to account for Shaw’s acquisition of Global TV in 2010 as well as Bell’s acquisition of CTV and Astral Media in 2011 and 2013, respectively.

Figure 6: Vertical Integration and Cross-Media Ownership — Canada in a Global Context, 2004 – 2013

Sources: see the “CrossOwnership Canada vs World” sheet in the CMCRP Workbook and International Media Concentration Research Project.

While the data upon which Figure 5 is based is dated, it is still the best available and, furthermore, there are no developments that I am aware of to suggest significant changes across the countries depicted that would counter the conclusions being presented here.

With those comments in mind, Figure 5 indicates that, by 2013, after Shaw and BCE acquired Global TV, CTV and Astral Media, respectively, Canada had the highest levels of vertical integration and cross-media ownership out of the 28 countries studied. It also shows that Canada has been closer to the high rather than the low end of the scale throughout the period covered when it comes to vertical integration and cross media ownership. It ranked 19th out of 28 in 2004. By 2009, however, it had moved closer to the top of the scale, with the third highest levels of vertical integration, after Finland and Sweden.

There has, of course, been an increase in vertical integration in the US on account of Comcast’s acquisition of NBCUniversal in 2011. And things could shift again if AT&T’s bid for Time Warner goes through but there is no reason to be sanguine regarding its prospects (see here, here and here). If that scenario does come to pass, the extent of vertical integration in the United States would more than double. The upshot remains, however, that even taking account of these recent and possible developments, conditions in the US fall well short of what they are in Canada. Moreover, beyond the US, for most countries depicted in Figure 6 above, the trend over time frame has been away from vertical integration not to its embrace.